Chevron’s Latest Step, by Nicholas Bednar

In West Virginia v. EPA, the Supreme Court held that the emission limits adopted by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the Clean Power Plan exceeded the agency’s authority, because the Clean Air Act did not clearly authorize the agency to “restructure the American energy market.” Ordinarily, courts would review the interpretive issue under the Chevron standard. Instead, the Court’s majority invoked the major-questions doctrine. As with other recent Supreme Court opinions, the majority did not even cite Chevron.The opinion has raised a flurry of questions in the administrative-law community. Is Chevron still alive? What constitutes a “major question”? How does the major-questions doctrine fit into Chevron’s framework—if it does at all?

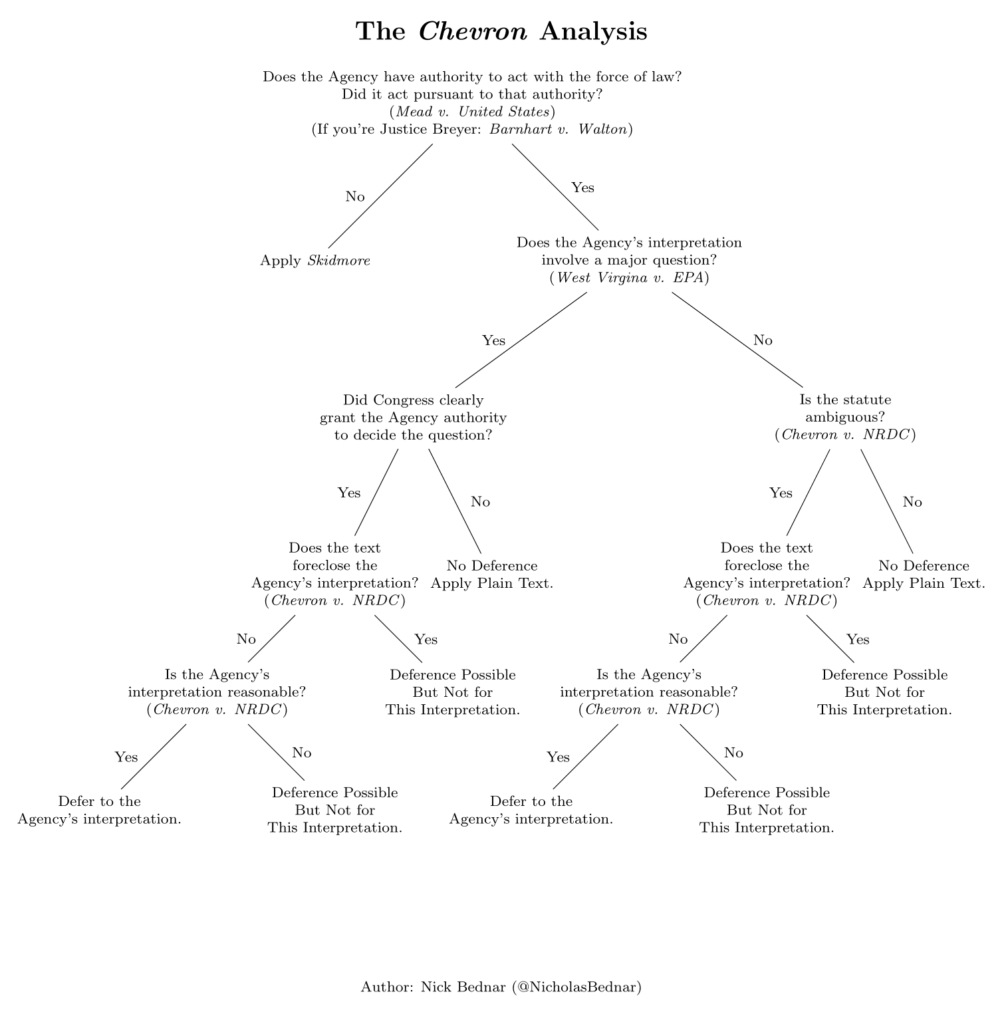

On Twitter, I attempted to answer this last question using the following flowchart. My goal: Determine how a lower court would apply the Chevron doctrine in light of West Virginia v. EPA.

The flowchart generated thought-provoking discussions about the major-questions doctrine, its application, and its relationship to Chevron. This post expands on my thinking to explain the choices made in developing the flowchart.

Some initial caveats. First, the flowchart does not opine on the normative or doctrinal validity of the major-questions doctrine.[1] It simply assumes that the doctrine exists and that lower courts will occasionally need to apply it. Second, the chart assumes Chevron’s persistence as a standard of review. In a post following American Hospital Association v. Becerra, Linda Jellum argues that the Supreme Court’s silence reflects that “Chevron deference is an ambiguity tiebreaker, much like the rule of lenity or the constitutional avoidance canon.” Perhaps. I hesitate to ascribe meaning to the Supreme Court’s silence—at least as it pertains to Chevron’s application in the lower courts. The lower courts still regularly apply Chevron as a multi-step standard of review. Therefore, it is appropriate to consider how lower courts will incorporate West Virginia v. EPA into the Chevron framework. Third and finally, with one notable exception (which I will discuss), the chart concerns the order of Chevron’s steps rather than the precise inquiry at each step. As Kristin Hickman and I have discussed, scholars and courts disagree about the substance of Chevron’s steps. For example, Step Two’s reasonableness inquiry could address either the zone of construction or State Farm. The same debate surrounds what constitutes a “major” question. Elsewhere, Kristin Hickman has attempted to pull a standard from West Virginia v. EPA. Others, like Blake Emerson and Beau Baumann, view the major-questions doctrine as a tool that allows courts to overturn decisions that conflict with their ideological preferences.[2] Regardless of the substantive inquiry, I tend to agree with Daniel Walters and Kristin Hickman that the major-questions doctrine will only be applied in a handful of cases.

The right side of the flowchart reflects the canonical Chevron analysis. When presented with an agency’s interpretation of a statute, the court uses Mead to decide which standard of review—Chevron or Skidmore—applies. If Congress delegated authority to the agency to take actions carrying the force of law (e.g., rulemaking or adjudication) and the agency acted pursuant to that authority, then the court reviews the interpretation under Chevron. Provided the interpretation does not concern a “major question” (however defined), the court moves to Chevron Step 1 and uses the traditional tools of statutory interpretation to assess whether Congress left a gap for the agency to fill. If the court finds Congress’s intent clear, then the inquiry ends because the court and the agency must apply the statute’s plain text. If the statute is ambiguous, then the court moves to Chevron Step 2. Chevron Step 2 takes two primary forms. Some judges use it to examine whether the agency’s interpretation clearly falls outside the intended meaning of an otherwise ambiguous statute. Others perform State Farm’s arbitrary-and-capricious analysis. Whatever its precise form, agencies that survive Chevron Step 1 rarely lose at Chevron Step 2. We can squabble at the margins about whether the flowchart should exclude certain steps or include other ones, but it otherwise represents an uncontroversial recitation of the Chevron standard.

The more interesting discussions occur on the left side of the flowchart, starting with “Does the Agency’s interpretation involve a major question?” Some have questioned whether the major-questions doctrine even belongs within the Chevron framework. On Twitter, Beau Baumann states, “I get the allure of a unified system, but I think we just ought to recognize these are separate doctrines.” In response to my original tweet, Evan Bernick states, “I think the MQD is no longer part of Chevron at all. It is free-standing. And once a question is major, you need to show a super-clear textual grant of authority or you lose.”

I think the major-questions doctrine belongs in the Chevron framework. For one, every Supreme Court case to apply the major-questions doctrine (or a proto-form of the doctrine) has involved an agency statutory interpretation that would normally receive Chevron deference. In FDA v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco, the Court began its analysis by stating that “this case involves an administrative agency’s construction of a statute that it administers, our analysis is governed by Chevron.” The Court continued that “In determining whether Congress has specifically addressed the question at issue, . . . we must be guided to a degree by common sense as to the manner in which Congress is likely to delegate a policy decision of such economic and political magnitude to an administrative agency.” Other early cases, including MCI Telecommunications v. AT&T, Utility Air Regulatory Group v. EPA, and King v. Burwell announce Chevron as the standard of review before applying some proto-form of the major-questions doctrine. The major-questions doctrine has only been applied in cases reviewing an interpretation would normally be reviewed under Chevron. Personally, I cannot think of another context where the major-questions doctrine would arise.Admittedly, the majority and concurrence in West Virginia v. EPA remain silent about the major-questions doctrine’s relationship to Chevron. But the Supreme Court has been silent about Chevron for years. Again, I hesitate to read the Supreme Court’s failure to cite Chevron as a sign that these two doctrines operate separately.[3]

In my mind, these doctrines are easily reconciled. Faced with ambiguity, Chevron presumes that Congress “left a gap for the agency to fill” and, therefore, the court must defer to the agency’s reasonable interpretation of the statute. Chevron applies in “ordinary” cases. However, if the court decides that the agency’s interpretation involves a “major question,” then the agency must show a clear statement from Congress that it intended for the agency to decide the question. The major-questions doctrine simply flips Chevron’s presumption of delegation. Ambiguity alone is sufficient to evidence delegation in “ordinary” cases, but a clear statement is necessary in “extraordinary” cases. Brown and Williamson affirms the major-question doctrine as flipping the standard presumption in Chevron.

Deference under Chevron to an agency’s construction of a statute that it administers is premised on the theory that a statute’s ambiguity constitutes an implicit delegation from Congress to the agency to fill in the statutory gaps. In extraordinary cases, however, there may be reason to hesitate before concluding that Congress has intended such an implicit delegation.

Even West Virginia v. EPA acknowledges the distinction between “ordinary” and “extraordinary” cases. In an “ordinary case” the political and economic “context has no great effect on the appropriate analysis.” But in an “extraordinary case,” “[t]he agency instead must point to ‘clear congressional authorization’ for the power it claims.”

The harder question is what happens once a court establishes that the agency’s interpretation involves a major question. If the agency cannot identify a clear statement delegating authority to the agency to decide the major question, then the agency loses. This outcome has occurred in every case where the Supreme Court has invoked the major-questions doctrine. We do not have strong evidence of what happens if the court (1) concludes that the agency’s interpretation involves a major question, but (2) finds that Congress clearly authorized the agency to decide the question. Admittedly, the final portion of the flowchart only guesses at the proper inquiry.

The only opinion to come close to resolving this issue is Judge Srinivasan’s concurrence in US Telecomm Association v. FCC. That case concerned the FCC’s 2015 Open Internet Order. Then-Judge Kavanaugh dissented, arguing that the D.C. Circuit should have invoked the major-questions doctrine. Judge Srinivasan responded,

Assuming the existence of the doctrine as they have expounded it, and assuming further that the rule in this case qualifies as a major one so as to bring the doctrine into play, the question posed by the doctrine is whether the FCC has clear congressional authorization to issue the rule. The answer is yes. Indeed, we know Congress vested the agency with authority to impose obligations like the ones instituted by the Order because the Supreme Court has specifically told us so.

He then went on to explain that Brand X ruled that the Communications Act left the decision to FCC to categorize broadband provides as either telecommunications services or information services. Therefore, US Telecomm is abnormal in that the D.C. Circuit believed that the Supreme Court had already decided the FCC possesses the authority to regulate broadband providers.

Hypothetically, there exists a case where a court finds that the agency has authority to regulate a major question, but that the agency has done so in an impermissible manner. This hypothetical court may find that Congress clearly delegated authority to the agency to address the question, but the agency addressed the question in a way that conflicts with the plain text of some other statutory provision. Alternatively, a court employing a State Farm-version of Step 2 may decide the agency arrived at its interpretation in an arbitrary-and-capricious manner.

Still, some individuals believe the major-questions doctrine is outcome determinative. Beau Baumann and I got into an extended discussion about whether anything follows the question of “Did Congress clearly grant the Agency authority to decide the question?” I think the disagreement stems from a lack of clarity about whether the major-question doctrine (1) requires a clear statement that Congress intended the exact interpretation advanced by the agency or (2) requires a clear statement that Congress intended to grant the agency the jurisdiction to resolve the question. Baumann favors the former interpretation. I favor the latter.

In my opinion, the major-questions doctrine asks whether the agency has jurisdiction to regulate in a particular area. Framed differently, can the agency reach into the zone of this major issue? Most major-questions cases have focused on concerns that the agency stepped beyond its jurisdiction: the FDA and tobacco, the CDC and evictions, and the IRS and healthcare markets. Even in West Virginia v. EPA, the majority focused on the fact that EPA does not have “comparative expertise” to regulate energy grids. The major-questions doctrine is ultimately a jurisdictional issue designed to prevent agencies from stepping beyond their expertise. As Kristin Hickman explained following King v. Burwell,a jurisdictional interpretation of the major-questions doctrine makes sense when one considers that Chief Justice Roberts argued in City of Arlington v. FCC that Chevron should not apply to questions related to an agency’s jurisdiction. Chief Justice Roberts authored both King v. Burwell and West Virginia v. EPA and has used the major-questions doctrine to place limits on Chevron’s application to questions of agency jurisdiction.

The concurrence and dissent debated the nature of the major-questions doctrine in US Telecomm. In dissent, then-Judge Kavanaugh argued that “Brand X’s finding of ambiguity by definition means that Congress has not clearly authorized the FCC to issue the net neutrality rule.” In contrast, the concurrence understood the issue as whether Congress clearly delegated authority to the agency to decide the question:

That analysis rests on a false equivalence: it incorrectly equates two distinct species of ambiguity. It is one thing to ask whether “Internet service is clearly a telecommunications service under the statute.” It is quite another thing to ask whether Congress has “clearly authorized the FCC to classify Internet service as a telecommunications service,” which is the relevant question under our colleague’s understanding of the major rules doctrine. The former question asks whether the statute itself clearly classifies ISPs as telecommunications providers. The latter asks whether the statute clearly authorizes the agency to classify ISPs as telecommunications providers.

Our colleague assumes that, if the answer to the former question is no, “that is the end of the game for the net neutrality rule.” Not at all. A negative answer to the former question hardly dictates a negative answer to the latter, more salient, one. The statute itself might be ambiguous about whether ISPs are to be treated as common carriers, but still be clear in authorizing the agency to resolve the question.

I favor the concurrence’s interpretation of the doctrine.

One final point: If the major-question doctrine requires Congress to provide a clear statement that it intends for the agency to adopt the exact interpretation at issue, then I am unsure how Congress could ever delegate a major question to the agency. For any major question, Congress must clearly codify its preferred interpretation rather than leaving the decision up to the agency. Perhaps that is intended result of the major-questions doctrine. However, if that is how the doctrine applies, then it seems a lot easier for the Supreme Court to say Congress cannot delegate major questions to administrative agencies than dance around how clear that delegation must be.

All-in-all, the flowchart provides a helpful exercise to think through the issues surrounding the major-questions doctrine. Many aspects of the major-question doctrine remain unclear. This flowchart is just one attempt to wrestle with its implications for lower courts in future cases.

Nicholas Bednar (@NicholasBednar) is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Political Science at Vanderbilt University.

[1] Personally, I remain skeptical that the major-questions doctrine has doctrinal or normative value. I believe standard tools of statutory interpretation would resolve many “major question” cases without the need to resort to a relatively amorphous doctrine. However, I am much more of an apologist for agency power than many of my peers in the administrative-law community. I tend to agree with Mortenson and Bagley that the Constitution does not envision a strong non-delegation doctrine. That said, I do understand the concerns raised by those who worry about agencies exceeding their statutory authority. For individuals with those concerns, the major-questions doctrine has great doctrinal and normative appeal. As applied, the major-questions doctrine seems like a far better and narrower alternative than the revival of a strong non-delegation doctrine. Perhaps as the major-questions doctrine percolates in the lower courts, I will be persuaded that it has doctrinal and normative value. As of today, I remain unconvinced.

[2] For the record, scholars of the attitudinal tradition argue that Chevron has the same flaw. However, Kent Barnett, Christina Boyd, and Chris Walker offer compelling empirical evidence that Chevron actually reduces partisan bias in judicial decisionmaking. Perhaps the major-questions doctrine will diminish Chevron’s constraining effect in the lower courts. Perhaps not. This is an empirical question that will take time to resolve.

[3] I will concede the following: In US Telecomm Association v. FCC, then-Judge Kavanaugh’s dissent describes Chevron and the major-questions doctrine as “two competing canons of statutory interpretation.” If Chevron is simply a canon of interpretation and not a standard of review, then perhaps both doctrines can operate separate from one another.