Silicon Rhymes with Savings and Loan (and It’s a Ratchet), by Anna Gelpern

Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) got big financing a shiny piece of the American Dream in a political fundraising hotspot. Its shareholders, its creditors, its regulators, and the public fell victim to the worldview and technology that had made it big. It died a badly run, badly supervised specialty bank.[*] The forceful federal response to its failure was unhampered by the guardrails installed after the last financial crisis. As usual (if exigent), the response sacrificed a quantum of regulatory credibility to stop the panic. Now we are haggling over the price.

What an old story. A cohort of newbies lend for Motherhood and Apple Pie, ignored by Wall Street behemoths. Mothers, children, apple pickers, and pie eaters everywhere cheer when their elected representatives relax rules to level the playing field for the newbies to compete with behemoths. Some apple pie banks grow big and strong, venture across the playing field, and forget about pie. A sudden storm—inflation, interest rate shocks, market gyrations—reveals a betting hall and pile of bad apples. Depositors run. Everyone gets twitchy. Someone on high says or does whatever it takes. Eventually the run stops and recriminations begin. This time is different; reform is nigh … but history rhymes.

Comparisons of regional bank troubles today to the U.S. Savings and Loan (S&L) crisis are gaining traction. The rhyme is right (interest rates!), but it misses the ratchet. Crisis containment strategies with roots in the 1980s operate by upending regulatory expectations: “whatever it takes” is a promise to break promises. Banks and governments renegotiate the regulatory bargain in the shadow of broken promises. The shadow just got longer.

An Existentially American Narrative

From 1893 to 1992, the housing finance lobby used the motto ‘The American Home: The Safeguard of American Liberties’. At the outset, state-chartered savings and loan associations (S&Ls, or thrifts) filled a gap left by commercial banks, which did not finance home mortgages. The Great Depression brought a federal thrift charter, a dedicated system of regulators, emergency liquidity from government-sponsored Federal Home Loan Banks, federal and state deposit insurance, and federal financing of home mortgages. S&Ls took deposits, made long-term mortgage loans, and became part of the American Dream—until nearly 1,300 of them failed in the 1980s and 1990s, exposing mismanagement, fraud, corruption, and regulatory capture, and leaving the government with a bill on the order of 2-3 percent of U.S. GDP.

Unlike S&Ls, SVB did not have a special charter, but it had a specialty. It lent to high-tech start-ups when few others would, and offered services that drew in their peers and funders. Its husbandry of the innovation ecosystem gave substance to its name, fused with essential inventions that Make-Us-Who-We-Are, from the internet to life-saving vaccines. SVB was bigger and more niche than the S&Ls, but it was part of a small banking cohort leaning into the upstart narrative. Banks like SVB and Signature, and the much-smaller Silvergate, smartly focused on fast-growing, underserved, politically salient sectors and regions, and cultivated a political base alongside their customer base. The niche business made SVB less stable than your regular unstable bank,[†] but it should have made the instability less worrisome for the rest of the world. Why would the general public see itself in a bank that was not ever a bank for the general public? Why would losing a firm dedicated to financing creative destruction pose “an existential risk to competition and innovation in the American economy”? It will take time to answer such questions with precision, but it hardly matters: the new baseline is that everyone is presumed systemic.

“In short, inflation and technology …”

Inflation, innovation and technology-related risks hover in the background of every banking business; managing them is part of the job description. In the 1980s, interest rates spiked into the double digits and kept on climbing, “unsticking” savers into new products like money market funds when statutory deposit rate caps limited S&Ls’ ability to attract deposits. The advent of computers (!!) sped up payments and undercut S&Ls’ information advantage, drawing big commercial banks and others into mortgage lending. The political base paid dividends when state and federal lawmakers started to compete to “level the playing field,” to help the S&Ls weather the economic cycle. With deregulation, some thrifts gave up on home mortgages altogether. The fix did not last.

Rising rates complicated life for SVB’s start-up borrowers, but were especially hard on its outsized portfolio of formerly boring bonds. Regulatory accounting let the bank treat mortgage-backed securities in 2022 as it would Aunt Agatha’s bicycle loan in 1940[‡]—ignoring market risk when it planned to wait for the debtor to repay the principal at maturity. Why sell a perfectly good bond before then? Because cash. Fabulous deposit growth that had reinforced SVB’s unique franchise narrative and propelled it from 37th to 16th largest U.S. bank in the United States turned into hot money, with $42 billion leaving in just one day. The same social networks and near-instantaneous communications that gave a $200 billion firm its community vibe, turned into concentrated deposit flight. The posse turned on one of its own so fast that it had no time to get to the Fed’s old-timey liquidity pipes. Blame the plumbing, blame Fed policy for making people forget about the 1980s (and the 2000s), blame social media silos for making people forget about the rest of the world, where these things happen.

Mistaken Identity

Leveling one playing field after another to help S&Ls hold on to their market share amid rising rates changed their asset portfolios beyond recognition. In some cases, “100 percent of their lending could (and did) go into wind farms, junk bonds, restaurants, Nevada brothels.” When the wacky investments went sour, the Bailey Building and Loan image turned out to be a mirage, as did some S&L deposit insurance schemes. The federal deposit insurer for S&Ls became insolvent in 1987, got recapitalized, then eliminated in 1989, its functions moved to FDIC—but federally insured depositors got paid. State-chartered insurance funds failed in California, Nebraska, Ohio, Maryland, Utah, Colorado, and Rhode Island. Pretend-insurance backed pretend-thrifts, but not real-life depositors.

Was SVB a bank? To be sure, “bank” means different things in different places, but the basic idea of parking your tuppence in a “safe and sound” marble box to feed some mix of local birds and “self-amortizing canals” is part of the culture. Faux bronze sealsassure that you are really banking with Uncle Sam, for all the good reasons you saw on TV.[§] SVB’s last Christmas was different. On the asset side, it was a bond fund grafted onto a smaller loan book. The bonds were booked at regulatory accounting values (no floating NAV for banks!), and paid for with residual claims on the liability side—uninsured, unsecured deposits from seemingly sophisticated socially networked investors. It kept a banking license, dressed up like a bank, and even suffered bank regulation, such as it was, but somewhere along the way it had stopped acting like a bank. Did anyone notice?

Laws, Rules, Feels

Lawmakers and regulators responded to brewing S&L problems by loosening restrictions on the industry and ignoring the rules still in place. In 1980, the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (DIDMCA) phased out deposit interest rate caps, lowered capital requirements, and broadened the range of permitted activities for federal thrifts. Two years later, the Garn-St. Germain Act allowed thrifts to offer insured money-market deposit accounts, variable-rate loans, and commercial real estate financing to help them compete in a rising interest rate environment. State authorities ratcheted up the pressure on federal authorities when they relaxed rules for the thrifts they chartered and supervised. In some cases, they went above and beyond: political leaders in Ohio helped cover up the condition of the state’s S&Ls, until the governor had to declare a bank holiday and close them all.

Officials’ indulgence of S&Ls’ desperate ventures was even more startling in their supervision, where political pressure was relentless, though obscured from public view. Texas and Arizona thrift executives repeatedly accused bank examiners of “Gestapo-like tactics,”[**] delaying and diverting enforcement actions while they lobbied for regulatory relief. In 1987, S&L regulators in Washington overrode San Francisco examiners’ recommendation to close Lincoln Savings and Loan, a notorious California thrift. In 1988, Washington took over (not) minding Lincoln from San Francisco. Soon after, Lincoln went under, its parent company went bankrupt, and its leadership faced multiple felony counts.

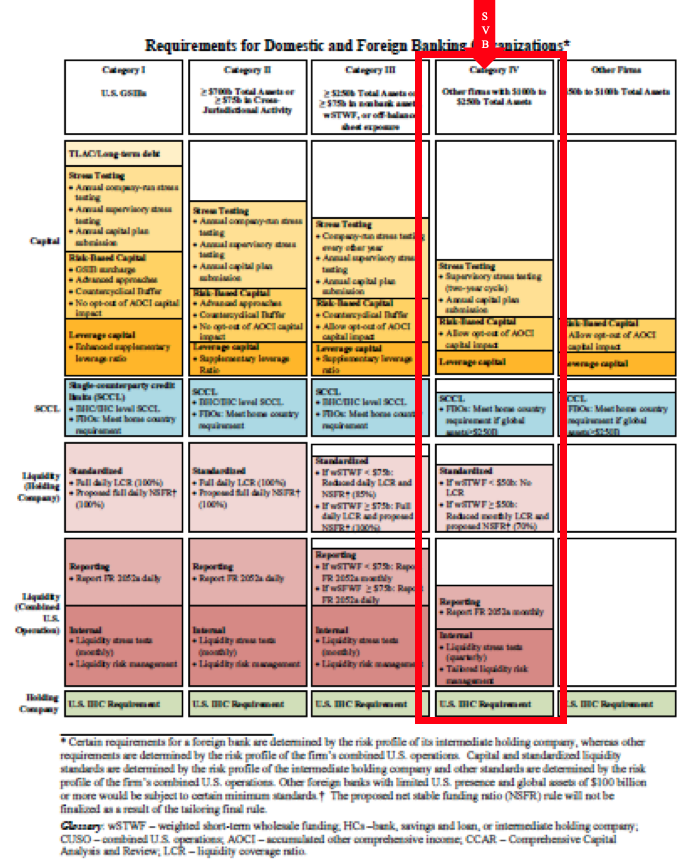

There is no evidence at this stage that crime killed SVB, nor that crude corruption or fear of exposing regional banks’ insolvency drove deregulation, the way they had in the S&L crisis. What we do know is not comforting. Much has been made of the 2018 “regulatory relief” legislation that weakened Dodd-Frank Act strictures on banks, of SVB executives’ lobbying for deregulation, and the Federal Reserve’s enthusiastic implementation of its deregulatory authority. Title IV of the 2018 law shifted presumptions of systemic-ness from banks with $50 billion to those with $250 billion in assets—the law literally says, cross out $50,000,000,000, replace with $250,000,000,000, over and over again—but allowed regulators to apply enhanced standards in a tailored way to banks with assets between $100 and $250 billion, if the Federal Reserve Board had good reasons to do it.[††] It purported to be a streamlining exercise; layered on top of an already-byzantine system, the result looked like this—

Technically, SVB’s deliverance from the most exacting belt-and-suspenders rules did not exempt it from supervision for “safety and soundness,” the hands-on, often granular and intrusive process to ensure that a bank is solvent, liquid, has a viable business model, and can manage the risks of liquidity and maturity transformation. In theory, bank examiners actually comb through files and spreadsheets, looking for crazy stuff like unhedged interest rate risk, or the doubling of an uninsured deposit base made up folks who hang out in the same chat rooms. Because it was a state-chartered bank and a member of the Federal Reserve System (a “state member bank), SVB could have not one, but three cohorts of examiners snooping around its innards. They were the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation, which had licensed SVB,[‡‡] the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, its lead federal regulator, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, its backup federal regulator. In addition, the Federal Reserve Board oversaw SVB’s holding company parent and presumably made the big supervisory policy calls for the bank itself, as a “large financial institution” (LFI) with more than $100 billion in assets.

Supervisory information is confidential, but we do know that SVB management got letters and had meetings as early as 2019. Why would the bank spring to action? Its federal regulators keep on writing. California’s website feels more come-hither than take-care: “regulatory authorities are encouraged to take a healthier, more positive posture on financial innovation and risk-taking when there are charter alternatives.” Even assuming no regulatory competition or corruption (SVB’s CEO was on the San Francisco Fed Board), it would not be strange for California and San Francisco Fed staff to believe in Silicon Valley genius. It was in the water.

The vibe from Washington was not exactly hostile either. The soup-to-nuts financial oversight review commissioned by the Trump Administration in 2017 chided supervisory stress tests for producing “unrealistically conservative results.” In December of 2018, then-Federal Reserve’s Vice Chair for Supervision and FDIC Chair toured the country “visiting bank examiners in regional offices and asking them to adopt a less-aggressive tone when flagging risky practices and pressing firms to change their behavior.” The FDIC Chair even invited the banks to tell on local examiners who are, in the bankers’ view, “overstepping their authority.”[§§] A supervisor reading this might think twice before asking rude questions about risk officer vacancies.

Libertarian zealotry is not a crime, nor is cultural capture. There is no jail or bankruptcy for either.

Bailouts and Blame

Since the collapse of SVB, the ether is awash in laments for our spineless bailout times. Legend has it that once upon a time, giants walked the earth refusing bailouts. S&L Hell opens with the scene of 6’7” Paul Volker rebuffing a governor’s plea to rescue his state’s S&Ls. In the 1980s and 1990s, thousands of banks and thrifts went into receivership, their equity wiped out, management ejected; thousands of people lost jobs; hundreds went to jail. No federally insured depositors lost money, but uninsured depositors did.[***]

A purely disciplinarian reading of the 1980s muddles the through-lines from then to now. The S&L crisis began with stagflation and interest rate shocks and unfolded amid public debt and deficit jitters. Bailout recriminations grew louder after the 1984 failure of Continental Illinois, a large commercial bank, when the FDIC paid off uninsured depositors and creditors. Politicians and policy makers came under pressure to push the cost of managing the crisis off the books and into the future.[†††] This made deregulation, forbearance, and wildly creative accounting especially attractive. As the crisis dragged on, the push and pull over burden-sharing produced a new crop of crisis management and bank resolution tools.

Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs)—a network of government-sponsored private lenders with a Depression-era housing finance mandate—proved useful at keeping S&L crisis costs off budget in the 1980s. Beginning in 1989, Congress authorized FHLBs to expand membership to commercial banks, which turned them into an obscure quasi-public backstop for the banking sector.FHLBs lent actively in 2007-2009 and during the COVID pandemic; they are newly notorious for financing SVB and others on their way to oblivion in 2023.

The 1980s also saw the FDIC experimenting with resolution tools, and negotiating the boundaries of its authority. Worries about the Federal Reserve’s willingness to lend to small non-member banks had led the Congress in 1950 to expand the FDIC’s toolkit to include “open bank assistance.” If the FDIC deemed a troubled bank “essential” to the community, it could use the insurance fund to keep the bank on life support (usually until it was sold). Between 1950 and 1982, the FDIC had a practice of limiting resolution costs, but its approach was not very rigorous, and did not apply in cases of “essentiality.” According to its own account of the 1980s, “When essentiality was invoked, cost considerations could be ignored.”[‡‡‡] Beginning in 1991, the FDIC’s choice of resolution tools became subject to a more stringent “least cost” test, limiting the scope for paying off uninsured depositors and bank creditors. Open bank assistance was still possible, but only under the so-called systemic risk exception, which replaced essentiality and could only be invoked with the approval of supermajorities of the FDIC and Federal Reserve boards, and the Treasury Secretary in consultation with the President. The FDIC used this exception in 2008 to establish system-wide transaction account and new bank debt guarantees, and to lend to Wachovia, Citigroup, and Bank of America. Post-crisis legislation narrowed the systemic risk exception again. It eliminated the option of invoking systemic risk for open-bank assistance: now the FDIC would have to kill a bank and attest to its systemic riskiness to rescue its uninsured.[§§§] (It did just that with SVB and Signature.) For the living, Dodd-Frank added separate FDIC authority to establish “widely available” guarantee programs subject to congressional approval on top of supermajority board votes.

The FDIC’s handling of SVB receivership and insurance feels like the clunkiest aspect of the episode so far. California authorities closed the bank on Friday morning—unusual timing, a sign of surprise?—and appointed FDIC as its receiver. SVB’s assets and uninsured liabilities became part of the receivership; its insured deposits were transferred to a Deposit Insurance National Bank (DINB), a special purpose bank usually associated with liquidation and depositor payoff. This may have signaled FDIC’s pessimism at the prospect of finding a buyer for the whole franchise, considering federal officials’ initial rejection of full deposit guarantees. U.S. authorities reversed course over the weekend, and invoked the systemic risk exception. Shareholders and some creditors lost all; all depositors were paid. SVB’s assets and liabilities reunited in a bridge bank set up to market the franchise.

The same 1991 law that made it harder for the FDIC to rescue the uninsured expanded the Fed’s Depression-era authority under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act to lend in “unusual and exigent circumstances.” It ca me in handy in 2008, in 2020, and again in 2023. Fears that Dodd-Frank reforms that confined this authority to facilities “with broad-based eligibility” would damage the Fed’s efficacy in crisis have proved unfounded so far. To the contrary, the string of crises has been a learning experience. The Fed’s post-SVB term financing program for banks adapts the design of its COVID-era predecessors. The most interesting thing about the 2023 facility was the intended borrowers—banks that could already access emergency liquidity from the Fed’s Discount Window, albeit for 90 days rather than a year. The unusual and exigent routine.

Is all that a bailout? The answer matters a lot, and not at all. SVB shareholders lost their bank, but they had a good run up until recently. More poignantly, uninsured depositors who believed that they were actually uninsured and sold their deposits at half-price to get cash from distressed debt investors must feel like chumps. Will everyday people’s taxes pay for bank failures, as they had in the S&L episode? It seems unlikely. The FDIC and the Fed have more assets on their hands, some of which may be risky. The Fed can afford to wait, and has a history of turning a profit for the taxpayer on rescue operations. If the insurance fund loses money—cost estimates now stand at about $20 billion for SVB alone—the FDIC must recoup it with a special assessment on those banks still standing. Banks can pass the costs to their customers. This has led to some uncomfortable conversations in Congress, but shed no light on loss distribution.

Another Crisis, Now What?

The arc of this crisis will be clear in retrospect, but preliminary take-aways are beginning to emerge.

Line-drawing for systemic-ness is a fool’s errand. If the end of a regional bank* with a niche clientele and a media megaphone warrants systemic risk exceptions for the FDIC and the Fed after Dodd-Frank reforms, then we are all systemic now.[****] The crisis before last transformed systemic risk from a scary thing into a decision-making roadmap. The roadmap is meant to guide real people in finance ministries, central banks, and deposit insurers, and hold them to account. If enough people in enumerated places are worried enough, they can attest to systemic risk, and access a special intervention toolkit. This decision framework is skewed in the worried direction, with a presumption in favor of systemic intervention.

Moral hazard arguments in crisis have traction on the sidelines, or after containment succeeds. This is because moral hazard is about the future; crisis containment is about living to see the future. Few policy makers would take a medium-sized risk of systemic collapse today for the sake of aligning incentives tomorrow.

This decision mindset is both prevalent and counterproductive in two ways. First, if intervention—eg, guaranteeing uninsured deposits—signals that officials are worried about midsize banks in general, it can fuel panic instead of stopping it. Second, even if intervention succeeds in the moment, it can corrode institutions and damage social fabric over time.

Credible crisis containment comes at the expense of credible regulation. It admits that rules failed, and/or must be broken. Rational panic means that prevention rules did not work. Irrational panic means that known crisis response tools are inadequate. Because near-miss and total miss are equally unacceptable, breaking rules is counterintuitively safe under the circumstances. It signals high stakes and ratchets up commitment to contain, Bagehot be darned.

Once containment succeeds, reviving regulatory credibility becomes a near-insurmountable challenge. The commitment problem is inherent in sovereignty; this crisis visibly reinforced the presumption that rules will be broken to stop the panic. All deposits in U.S. banks are presumptively guaranteed. “Are,” not “should be,” because total coverage appears to be the practice in crisis and is baked into system architecture, despite squishy official denials. This is regressive, creates perverse incentives for potential rescue recipients to fan crisis flames, and sets up an immediate political economy and institutional design problem.

As a matter of design, the SVB episode illustrates starkly that a banking license is no guarantee of bank behavior, bank management, bank regulation, or bank supervision. Designs that separate core public service provision and private risk-taking should enhance credibility, because they focus monitoring and limit hold-up opportunities. Turning to utility-style organization and regulation of some service provision, accelerating and expanding the scope for central bank digital currencies, and outright nationalization could become more prevalent after the recent experience. Higher insurance assessments, more and better capital, more and better liquidity, and more adverse stress test assumptions are all on the table—but will they stick, with the credibility reservoir on fumes?

In the 1980s and the 2020s, specialty banks have posed special supervision challenges. They may have distinct business models, information sources, geographic and industry concentration risks; they may also enjoy community loyalty, a political base and a media platform. Their specialty may be a public good, and a good argument for special dispensations—or even their own charter. But someone will have to hold the bank to the specialty, and make sure that it does not use special dispensations to take undue risks. The civil servant in that job might have all the human priors—even local pride! The U.S. supervision structure, with layered state and federal oversight, could be a useful institutional check on local examiner biases, until the specialty banking cohort gains political traction at the center. Even the most hard-nosed bank examiner is stuck between the supervised rock and the political hard place.

Banks are inherently unstable and chronically misunderstood by the public. This is disconcerting because they perform essential functions and are not going away. In March 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt devoted his first “fireside chat” to explaining banks to people who just had their savings locked up in a nationwide bank holiday, before there was the FDIC or the Fed as we know it. At times, FDR sounded like today’s leaders:

Some of our bankers…had used the money entrusted to them in speculations and unwise loans. This was of course not true in the vast majority of our banks but it was true in enough of them to shock the people for a time into a sense of insecurity and to put them into a frame of mind where they did not differentiate, but seemed to assume that the acts of a comparative few had tainted them all.

Elsewhere, he told people that they would lose money and, at the same time, invested them with the success of the plan:

I do not promise you that every bank will be reopened or that individual losses will not be suffered, but there will be no losses that possibly could be avoided; and there would have been more and greater losses had we continued to drift. … We have provided the machinery to restore our financial system; it is up to you to support and make it work. … It is your problem no less than it is mine. Together we cannot fail.

A whole lot of horse-trading and weedy institutional work came next. Narrative matters, history rhymes, etc.

Anna Gelpern is the Scott K. Ginsburg Professor of Law and International Finance at Georgetown University Law Center. The author is grateful to Peter Conti-Brown, Adam Levitin, Patricia McCoy, Alexander Nye, Saule Omarova, Heidi Mandanis Schooner, Brad Setser, Robin Wigglesworth, and Arthur E. Wilmarth for comments and insights, and to Nat Deacon for valuable research assistance.

[*] -ing license holder (see below)

[†] Making long-term loans against no-term demand liabilities is unstable by definition. That’s why we have deposit insurance and lender of last resort.

[‡] If Aunt Agatha were a risk-free borrower issuing the global reserve currency that could tell its banks to ignore the thought of credit risk when it came to her debt.

[§] I have vented elsewhere on the subject of businesses, however small, plonking millions in a box without bothering to Google FDIC *FAQ* on how deposit insurance works (PSA here). It does not take monitoring a bank.

[**][**] Calling wonky U.S. civil servants by the name of Hitler’s secret police is a time-honored tradition in some political circles.

[††] The Federal Reserve Board would have to determine that stricter oversight was “appropriate … to prevent or mitigate risks to the financial stability of the United States, …; or … to promote the safety and soundness of

the bank holding company or bank holding companies.” (Sec. 401)

[‡‡] … back when it was called the State Banking Department, decades before it merged with the state corporations chartering authority and got “innovation” in its name.

[§§] Unfortunate considering the use of secret police rhetoric against civil servants.

[***] Between 1986 and 1993, uninsured deposits stood at 3 percent of total deposits.

[†††][†††] For big banks with exposure to developing countries—including Continental Illinois—regulatory forbearance also helped shift the cost of bad loans to those countries, some of which are living with the consequences to this day. Bank capital tables in this book illustrate.

[‡‡‡] The sentiment survives its original context. A 1982 law introduced a cost test and expanded the scope for open bank assistance. An essentiality finding would only be required if keeping the bank alive would exceed the cost of liquidation.

[§§§] Sec. 1106

[****] … unless the ongoing-but-already-forgotten self-liquidation of Silvergate bank defines success, which is not totally crazy.