What’s In a Name? Urban Infrastructure and Social Justice, by Rebecca Bratspies

Arriving in New York City, you might take the Van Wyck Expressway past the Jackie Robinson Parkway on your way from JFK airport. Or you might cross the Kościuszko Bridge as you travel from LaGuardia airport. Or you might take the George Washington Bridge to the Major Deegan Expressway. Or, you might use the Goethals Bridge, or the Pulaski Skyway, or the Outerbridge Crossing. What, if anything, would those trips tell you about the city (other than that we desperately need better mass transit?) All this infrastructure commemorates individuals who helped shape the city’s history. Yet, few people remember that, before these names became a shorthand for urban congestion, they were actual people.

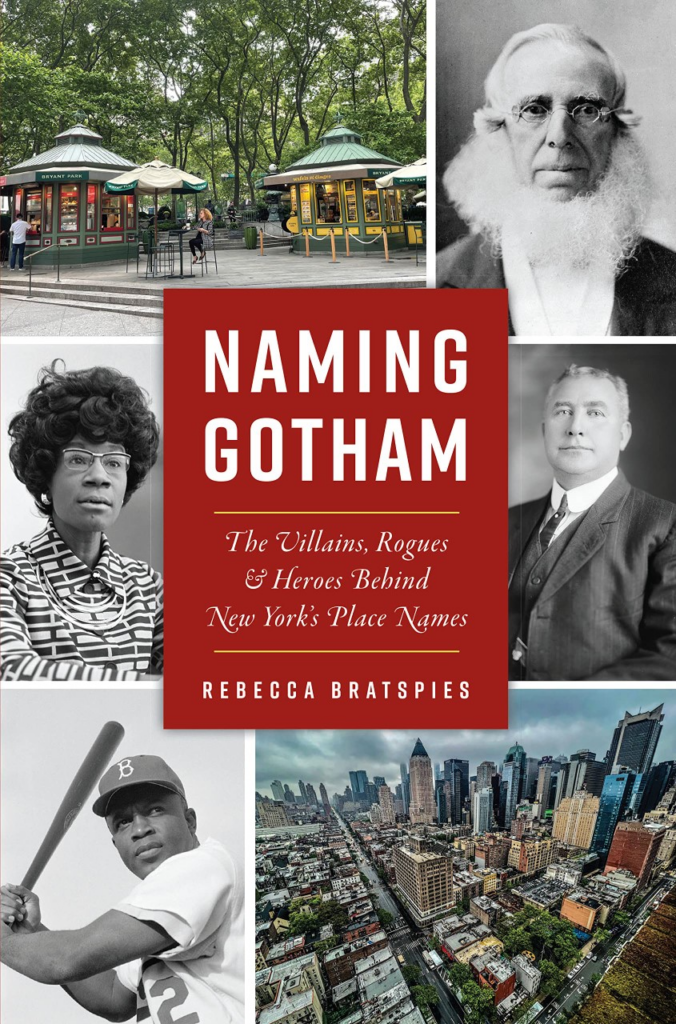

In Naming Gotham: The Villains, Rogues, and Heroes Behind New York Place Names, I set out to remedy this situation. Using mostly archival sources, each chapter offers a deep dive into the life of someone the city has chosen to honor. (You can watch the book trailer for Naming Gotham here.)

Some of the figures were truly remarkable—like Revolutionary War hero and anti-slavery advocate Tadeusz Kościuszko, or inventor/philanthropist Peter Cooper. But a surprising number were mid-level government functionaries whose main claim to fame was being Robert Moses-adjacent and dying while he was building something (most likely yet-another highway rammed through the Bronx.) Henry Bruckner, Arthur Sheridan and Major Deegan fall into what I would call the Robert Moses club, with the much earlier Van Wyck as perhaps an honorary member.

The names attached to New York City’s roads, bridges, and other civic infrastructure tell us a lot about who we think we are as a city. Looking across the city as a whole, one fact stands out. Virtually all the people with roads or bridges named after them were white men. In a city as diverse as New York, this speaks volumes—about who had the power to name things, and who got to decide what counted as history. There are, of course, exceptions. In 1997, the Interboro Parkway was renamed for legendary baseball player Jackie Robinson. And, the Hutchinson River Parkway, like the river it tracks, is named after Puritan religious leader Ann Hutchinson.

Over the past few years, there have been growing calls to name more infrastructure and landmarks for the wide array of remarkable women and people of color. As I wrote Naming Gotham, this began to happen. Statues recognizing a range of Black Americans including Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Ralph Ellison and Duke Ellington have been erected across the City. A statue of women’s rights pioneers Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony sits in Central Park. Just last month, New York dedicated the Gate of the Exonerated. Perhaps the City’s biggest step forward came in 2019, with the opening of the Shirley Chisholm State Park in Brooklyn. The park honors ‘fighting’ Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman elected to Congress, and life-long Brooklyn resident.

Renaming existing infrastructure to better reflect our shared history is more challenging. While much attention has been focused on removal of Confederate statutes and monuments sited in southern states during the Jim Crow era, and renaming streets that honored Confederate officers who took up arms against the United States, that is only one aspect of a fundamental, society-wide reconsideration of who we name things for. Hastings Law School renamed itself UC College of Law, San Francisco, removing Serranus C Hastings’ name because of his role in genocide against the Yuki Indians. Similarly, the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law rebranded itself CSU Law School removing Chief Justice John Marshall’s name because of his participation in the slave economy. More than 80 public schools across the country have responded to student pressure by dropping confederate names, and sports teams face growing pressure to change racist mascots.

New York City has its own reckoning to grapple with. In 2018, New York City’s Public Design Commission voted unanimously to remove a statue of J. Marion Sims from Central Park. Often called the father of gynecology, Sims routinely experimented on enslaved women. Removing the statue was an important step in recognizing structural racism encoded in city monuments. Yet, the mayor still lives in Gracie manor, named for slave-owner Archibald Gracie, and almost certainly build with enslaved labor. Lenox Hill and Lenox Avenue bear the name of Robert and James Lenox, whose family enslaved people and whose fortune was deeply entwined with the slave economy. The City sends its pre-trial detainees to Rikers Island, named for a family that profited from enslaved labor, and whose most famous member, Richard Riker abused his position as City Recorder to participate in what came to be known as the Kidnapping Club—a scheme that used the Fugitive Slave Act to sell free Black New Yorkers into slavery. At least the Rikers name will likely soon be gone. By 2027, the City will close the jail and convert the (most-likely-renamed) island to renewable energy generation. Lennox Avenue is increasingly known by its alternate name, Malcom X. Boulevard. But what of Gracie Mansion? Of Lennox Hill? Of other similarly situated places, like Macomb’s Dam Bridge?

The importance of naming, and renaming in New York City, has garnered increasing attention, but the process is not easy. It requires a petition with 200 signatures, approval of the local community board, legislation passed by city council and signed by the mayor. Since 1992, the process became a bit simpler because Local Law 28 has allowed City Council to add honorary street co-names, without triggering a need to amend the official city map. Since then, honorary co-names have proliferated. Nearly 1/5 of these honorary co-names memorialize people killed on 9/11. Others are named for local leaders, or for civil servants, like Frank Justich Way, named for a sanitation worker killed on the job in 2010). The Queens Library recently launched the Queens Name Explorer Map, a participatory digital archive focused on schools and honorary street names in Queens. The goal is to collect personal histories about, and images of these local honorees.

Bigger changes may be in the works. For the past three sessions, the New York legislature has fielded a bill to rename the Queens Midtown Tunnel in honor of Jane Matilda Bolin—the first Black woman to serve as a judge in the United States. Judge Bolin was appointed to the bench by Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, himself the first Italian-American elected to Congress. The Bolin bill, and a companion bill to rename individual spans of the RFK/Triborough Bridge for Robert F. Kennedy, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Puerto Rico independence leader Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos, have yet to make it out of committee. Part of the reason may be simple resistance to the expense and hassle of renaming.

Former Governor Andrew Cuomo created a firestorm with his decision to rename the replacement Tappen Zee Bridge as the Governor Mario M. Cuomo Bridge in honor of his father, three term governor, Mario M. Cuomo. Although he eventually persuaded the New York legislature to enact the requisite legislation, whether local residents will use the new name remains in doubt. After Governor Andrew Cuomo resigned in disgrace, there have been multiple bills proposing returning the bridge name to Tappen Zee.

Similarly there was little popular support for the 2010 renaming of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel to honor former Governor Hugh L. Carey, or of 59th Street/Queensboro Bridge as the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge. Indeed, only after fourteen years and $4 million spent on new road signs has the name RFK Bridge slowly entered common parlance alongside the “real” name, the Triborough Bridge.

I hope I have piqued your interest. On a more personal note, writing Naming Gotham was a labor of love. It started when my partner, composer Allen Schulz, suffered a catastrophic cardiac arrest. He was in the hospital for 6+ months, with the first month in a coma hanging between life and death. With no emotional energy for my usual environmental scholarship, I still desperately needed a project to keep me mentally engaged as I sat by his bedside. Allen and I used to get stuck in traffic on the Major Deegan every time we tried to visit my parents in Pennsylvania. I would always grumble “who was that Major Deegan anyway.” Allen would challenge me to find out. So, working on this book was a way to connect with our past as I waited to see if we would have a future. That story has a happy ending. Although he has limitations, Allen made a truly miraculous recovery and is even able to compose again.

Rebecca Bratspies is a Professor of Law at CUNY School of Law, where she directs the Center for Urban Environmental Reform.