Can Courts Review Agency Fact-Finding Without the Help of ALJs? By Lydia K. Fuller and Daniel B. Listwa

A tide of skepticism of the administrative state has been rising among members of the judiciary and the academy—a trend only encouraged by the Trump administration’s resistance to the modern federal bureaucracy. In the last two Supreme Court Terms, this skeptical upswell has translated into a number of remarkable cases challenging key tenets of administrative law, from the appointment of Administrative Law Judges (ALJs) in Lucia to the strength of deference to agency interpretations in Kisor. Each of these cases can be related to a multi-pronged program of reform that dates back at least to Gary Lawson’s well-known essay, The Rise and Rise of the Administrative State. Lawson argued that modern administrative law doctrine undermined important structural constraints imposed on the federal government by the Constitution. For example, he argued, the independence afforded to certain agency actors like ALJs insulates them from the President, making them unaccountable to the voting public; and the deference to agencies provided by doctrines like Chevron and Auer undercuts the important check that ought to be provided by the judiciary.

For those in agreement that the administrative state needs greater restraining, the Court’s apparent openness to revisiting longstanding practices would seem to be heartening (even if the results have been limited). But in our forthcoming Note in the Yale Law Journal, “Constraint Through Independence,” we offer a counterintuitive insight. Using both a qualitative deep-dive into case law and a first-of-its-kind empirical study, we show that attacking the independence of ALJs would likely undercut the effectiveness of judicial review of agency adjudications. The reasoning is simple: judges rely on ALJs to alert them (through “red flags” in the initial record) when agencies are potentially manipulating the facts, thus facilitating judicial review of agency fact-finding. Our data shows that unless the ALJ plants such a “red flag,” courts are unlikely to overturn the agency on the facts.

The focus of our study is the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), one of the administrative agencies that most heavily relies upon adjudication, as opposed to notice-and-comment rulemaking, to develop its policies and enforce its regulatory mandate. ALJs frequently are the initial fact finders in NLRB cases, holding evidentiary hearings, building records, and reaching decisions that are often appealed to the politically appointed agency heads. It is the agency’s decision that is then reviewed by the federal circuit courts. By analyzing hundreds of these federal appellate cases, we noticed a clear pattern. Although the courts were frequently willing to overturn the NLRB for disagreement with the agency’s legal conclusions, they rarely questioned the agency’s fact-finding—that is, unless an ALJ had said something on the record that raised an alarm.

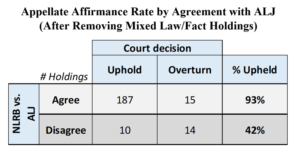

While we first noticed this trend by comprehensively reading a large number of recent decisions, we then sought a more rigorous form of confirmation. We pulled every appellate court case from the past five U.S. Government fiscal years involving the NLRB, and coded every “substantial evidence” holding in those cases—i.e., every holding declaring a finding of fact made by the NLRB to be “supported” or “unsupported” by substantial evidence in the administrative record. That amounted to nearly 300 holdings. We coded the holdings on two dimensions: first, whether the NLRB had agreed or disagreed with the ALJ on the factual finding at issue (“Agree/Disagree”), and second, whether the appellate court upheld or overturned the NLRB with regard to that finding (“Uphold/Overturn”).

The results were staggering. Where the NLRB and ALJ had agreed, appellate courts upheld the NLRB’s findings of fact 84% of the time. Where they disagreed, this figure plummeted to a 43% affirmance rate. The difference was even more remarkable when we removed holdings involving mixed issues of law and fact (a concept that we explain in our Note), leaving in only holdings based purely on factual issues. Among that narrower set of holdings, 93% of instances in which the ALJ and NLRB agreed were upheld while the affirmance rate for instances in which the ALJ and NLRB disagreed was merely 42%. In other words, whether the court overturned an agency finding of fact or not was highly dependent on when the ALJ and NLRB disagreed. Indeed, a chi-square statistical test supported a finding of such a dependence to a very high degree of statistical significance.

These findings should give pause to anyone interested in the current state of administrative law—but especially to those pushing for reform. In July of 2018, following the Court’s decision in Lucia that the SEC’s ALJs are Officers of the United States, the Trump administration issued an executive order that excepted ALJs from the relatively apolitical, centralized hiring process run by the Office of Personnel Management and moved hiring decisions to the decentralized discretion of politically-appointed agency heads. The same month, the Solicitor General issued a guidance memorandum warning that removal protections for ALJs would pass constitutional muster only if “suitably deferential” to these agency heads.

While these reforms might provide greater political accountability, they do so by weakening the separation between the ALJs and the agency heads. The underbelly of “political accountability” is that ALJs will likely become more accommodating to agency heads’ positions, leading to less disagreement and, thus, fewer “red flags” in the administrative record. Based on what we have observed, the absence of such “red flags” would negatively impact courts’ ability to constrain agencies through judicial review of their fact-finding. In other words, ALJ independence and judicial constraint of agencies are intimately linked. Efforts to weaken independence weaken constraint.

The problem is only compounded when restrictions on ALJ independence are combined with the second prong of the administrative skeptics’ program, the elimination of deference regimes like Chevron and Auer. Each of these doctrines gives agencies some leeway with regard to judicial review of their legal interpretations: even if the court does not precisely agree with the agency’s conclusion, the agency’s interpretation of the statute or regulation is allowed to stand. Doing away with those doctrines undercuts agencies’ ability to achieve policy goals through statutory or regulatory interpretation. But the agencies are not left without recourse. Faced with greater pressure in the sphere of legal conclusions, agencies are incentivized to make policy through fact-finding, a process Brinkerhoff and Listwa discussed in a recent essay. Agencies following such an approach need not convince courts to accept novel theories of statutory and regulatory interpretation; they need only shape their factual findings such that, when combined with existing legal rules, they mandate the agencies’ desired ends.

But there’s the rub. As our Note shows and as explained above, independent ALJs are central to judges’ efforts to spot factual manipulation by agencies in the context of adjudication; as a result, restrictions on the appointment and removal protections afforded to ALJs risk undercutting judicial review of agency fact-finding. And yet, efforts to eliminate deference regimes increase the likelihood that such judicial scrutiny of the facts is necessary—because the “facts” just may be where the most daring policies are made. This places a deep contradiction in the center of the administrative skeptics’ program. Although the prongs of reform might be defensible individually, when combined they lead to counterintuitive results. Our recommendation: those pressing for reform must adopt a more system-level approach to understanding the administrative state, one that is attentive to the sometimes unexpected ways in which mechanisms of legal interpretation and fact-finding; independence and constraint; political accountability and judicial reviewability interact. It is our view that once this bigger picture is adopted, doing away with independent ALJs is exposed as a problematic threat to our democratic system of checks and balances—and hardly a panacea for concerns about administrative constraint.