Chevron Deference vs. Steady Administration

When the Supreme Court met last week to reconsider judicial deference to agencies’ legal interpretations, the justices grappled with one of the most unsettling qualities of modern government: sweeping policy changes from one administration to the next, which create immense regulatory uncertainty.

Chevron deference “ushers in shocks to the system every four or eight years when a new administration comes in,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh said, “from pillar to post.” Far from creating a body of law that people can rely on, he continued, Chevron fosters “massive change … not stability.” Justice Neil Gorsuch pressed the point, too: the Court’s modern deference doctrine “is a recipe for instability,” because “each new administration can come in and undo the work of a prior one.”

They’re right. The administrative state’s ruinous instability is one of the worst vices of modern American government. But it is not just a novel problem of modern politics. The justices are gravitating toward one of the most important themes of our nation’s founding: the fundamental need for “steady administration.”

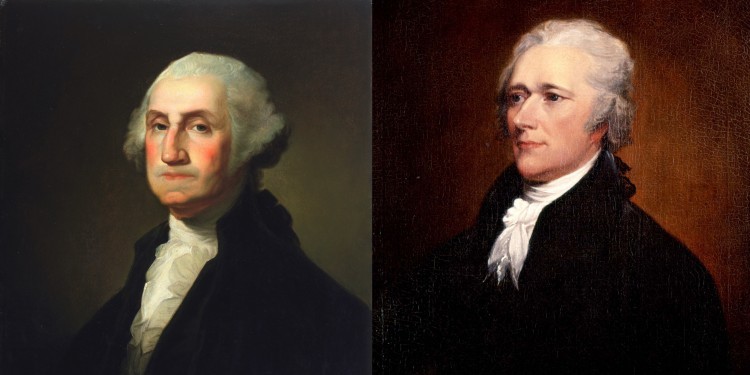

It was central to The Federalist’s argument for the constitutional presidency. Alexander Hamilton argument for “energy in the executive” is famous, but even those who read Federalist 70 often miss his deeper point. Energetic presidents aren’t inherently good. Rather, presidential energy is good for a few important things—especially, Hamilton argued, for “the steady administration of the laws.”

On that point, Hamilton’s broader argument for the presidency—with a long four-year term and the chance for re-election—was an argument for minimizing disruption from one administration to the next. Of course the presidency would change hands, and of course policies would change from one president to the next; that’s the point of elections. But as Hamilton warned in The Federalist, too much change from one administration to the next would risk “a disgraceful and ruinous mutability in the administration of the government.” At its best, the constitutional presidency would promote “the stability of the system of administration,” reinforcing a rule of law that lays the foundation for the rest of us to live our lives and plan for the future with as much certainty as one can reasonably expect in a democracy. At its worst, unstable administration wrecks the rule of law and, eventually, people’s respect for government itself.

Hamilton wasn’t the only one to make this point. Alarm for ineffectual, “mutable” administration resonates through the best parts of our founding generation. James Madison’s criticism of the early state governments, recorded in his 1787 memo on the “Vices of the Political System of the United States,” emphasized not just the overbearing “multiplicity” of laws, but also the pathetic “mutability” of their laws—two sides of the same coin. And George Washington knew the dangers of unsteady government from both his wartime service and his post-war life, so he built a presidency that embodied good, steady administration.

But since then, too much of our history has undermined steady administration, bringing us to an era when government is defined by whiplash-inducing legal changes from one president to the next. Today’s style of government, where presidential elections are “everything elections” and each one feels like a regime change is, frankly, Hamilton’s nightmare.

Chevron deference contributed to this decline. As the justices emphasized throughout last week’s hours of oral argument, Chevron expanded each new presidential administration’s policymaking discretion. It was, to be fair, well-intentioned: after decades of judicial micromanagement of presidential regulatory reforms, the Chevron Court concluded that Congress’s broad delegations of power to the executive branch were best managed by elected presidents, not unelected judges. Justice Antonin Scalia, Chevron’s wisest and most eloquent defender, argued that judicial deference to an administration’s reasonable interpretation of a truly vague statute would “permit needed flexibility, and appropriate political participation, in the administrative process.” The best remedy for a bad policy would be the next election’s good changes.

But even Scalia knew that you can have too much of a good thing. In his seminal defense of Chevron, a 1989 article for the Duke Law Journal, he conceded that “at some point, I suppose, repeated changes back and forth may rise (or descend) to the level of ‘arbitrary and capricious,’ and thus unlawful, agency action.” His quip has been largely overlooked. It deserves much closer attention, especially now.

Scalia didn’t specify the line limiting excessive administrative change. But thirty-five years of unsteady administration—not just on minor regulatory details but also on what the Court now calls “major questions”— have surely obliterated any reasonable limits. Even justices and judges who were long sympathetic to Chevron sense that something has gone badly wrong with the project. (Scalia himself, who exemplified “prudence” in his administrative law jurisprudence, clearly seemed to develop doubts of his own.) Their questions about modern agency flip-flops echo Scalia’s quiet caveat—and the Founders’ vocal warnings.

Congress created unsteady administration by delegating broad powers to agencies, often in the vaguest possible words. Steady administration is always difficult, but especially in the absence of clear laws. Justice Elena Kagan pressed this point throughout the oral arguments, challenging the lawyers to explain how courts could turn vague laws into clear rules.

Reformers can’t simply wave the vagueness problem away. But, again, the founders knew the answer, and it lies in good administration. Congress should legislate as clearly as possibly, but when vagueness remains, the task of administration is to promote steadiness, not unsteadiness. Good administration will “liquidate” vague laws (in Madison’s and Hamilton’s word) into a clear rule of law. And the courts complete the process by eventually settling the meaning of vague laws, according to their original meaning but, when in doubt, with an eye to the experience gleaned by good administration. The courts must do their own constitutional job, and in a way that best helps the other branches to do their own constitutional jobs. There may be room for some judicial deference to agencies as they work out the precise meaning of a vague law, at least when the law is new, but eventually the courts must settle the question. A law’s meaning cannot remain perpetually unsettled.

The Court seems to be gravitating in the right direction. (Indeed, the Roberts Court has seemed uniquely attuned to the need for steadier administration for years.) Perhaps it will fix Chevron deference by recalibrating it to give more deference to steadier interpretations of law than to constant flip-flops, as it did to another category of judicial deference a few years ago in Kisor v. Wilkie. This would be a welcome reform, responding to modern problems and resonating with the founders’ constitutional wisdom.

Hamilton knew that “the true test of good government is its aptitude and tendency to produce a good administration.” For too long, we have been failing that test. The Supreme Court can help bring government back toward the constitutional goal of steady administration.

Adam White is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, co-director of the Antonin Scalia Law School’s C. Boyden Gray Center for the Study of the Administrative State, and chairman of the American Bar Association’s Administrative Law Section.