Chief Justice Taft, President Taft, and the Myers case

How much power does the Constitution give the President to fire the heads of departments, and what does this imply about lower-level civil servants who staff those departments? The former question has been debated since the First Congress, of course; and the latter question since the Pendleton Act. And both questions are once again in the front of our minds in the aftermath of Lucia v. SEC and Seila Law v. CFPB—and with Collins v. Mnuchin soon to follow.

As we grapple with these questions, we benefit from the work of scholars who carefully research the historical record with an eye to modern controversies. Aditya Bamzai exemplified such work this year in his study of “Tenure of Office and the Treasury,” and in his paper last year on “Taft, Frankfurter, and the First Presidential For-Cause Removal.”

And now Robert Post has published his own study of Taft and removal—not President Taft’s removal of officers, but Chief Justice Taft’s view of the removal power in Myers v. United States. For those of us looking forward to Post’s contribution to the Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise History of the Supreme Court of the United States (Volume X, on the Taft Court), this article is a nice preview of coming attractions. And for students of constitutional law and administration, this article, newly published in the Journal of Supreme Court History (and available in draft on SSRN), is a must-read.

In “Tension in the Unitary Executive: How Taft Constructed the Epochal Opinion of Myers v. United States,” Post explores Taft’s correspondence and other records to reconstruct the Court’s consideration of the Myers case, from its oral argument in December 1924 (not 1923, as erroneously marked by the United States Reports) and re-argument with the newly seated Justice Harlan Stone in April 1925, until its decision nearly two years later. He describes an extraordinary process in which the Chief Justice worked to produce a majority opinion initially on his own (beginning at his summer home in Murray Bay, Canada), before enlisting colleagues’ help in a belabored process of writing and re-writing.

“It would be accurate to say that the Myers opinion was constituted through a most unusual process,” Post concludes. “There appears to be nothing even remotely analogous during the entire Taft Court era,” in which the Chief “essentially constituted his majority of six into a committee that met twice at his home to discuss the holding, structure, and argument of Taft’s drafts.”

By the end, Taft is exasperated by the new Justice (i.e., future Chief Justice) Stone’s relentless barrage of suggestions. Months into drafting, Taft writes to his brother Horace that “youngest member Stone is intensely interested and is a little bit fussy,” and “betrays in some degree a little of the legal school master—a tendency which experience in the Court is likely to moderate.” A week later he wrote to Justice Van Devanter, “Stone continues to tinker, but I don’t think he helps much.”

Yet Justice Stone’s barrage of comments amplified the crucial issue of how far Chief Justice Taft’s logic of executive removal power would cut. And that is the crux of Post’s account: once Chief Justice Taft reached the conclusion that the Constitution empowered the President to remove officers such as Portland’s Postmaster Myers, he needed to explain how far the logic of presidential removal power would cut—to executive officers alone, or to members of independent regulatory commissions, or to members of the civil service?

Post parses Taft’s opinion, especially in light of Justices Brandeis’s and McReynolds’s dissents, and concludes that Taft fell short of the analytic task. “At root,” Post writes, “the weakness of Taft’s position lay in its failure to specify the precise circumstances that required unfettered executive control.”

Moreover, while Taft’s opinion for the Court is remembered for exalting executive power, Post emphasizes that its attempt to identify a limiting principle (in response to McReynolds’s pointed dissent) seemed to concede immense power to Congress. For while Taft’s majority opinion held in favor of unfettered presidential power to remove principal officers, it further explained that an inferior officer, for whom Congress had vested appointment power in the department head rather than the President, might not be removable by the President at will after all. In drawing that line, Post writes, “Taft thus constructed an argument effectively ceding to Congress constitutional authority to determine when discretionary removal power for inferior executive officers was and was not prerequisite for the president’s capacity to execute the laws.”

It is a fascinating account, and Post connects it to modern debates surrounding executive power and originalism. It will entertain its readers and challenge them—especially those of us who are inclined to disagree with the conclusions that he draws with respect to independent agencies specifically, or Originalism and the “unitary executive” more broadly.

Sidestepping doctrinal questions, I would add to Post’s narrative one more story that I think illuminates Taft’s thinking in Myers.

Post connects Chief Justice Taft’s analysis to President Taft’s experience, writing that the Chief Justice “did not approach the Myers case as a blank slate … He would bring to Myers the entire weight of his considerable presidential experience.” Surely this is true, and to Post’s account of Taft’s presidency I would add still one more important episode: the Gifford Pinchot affair.

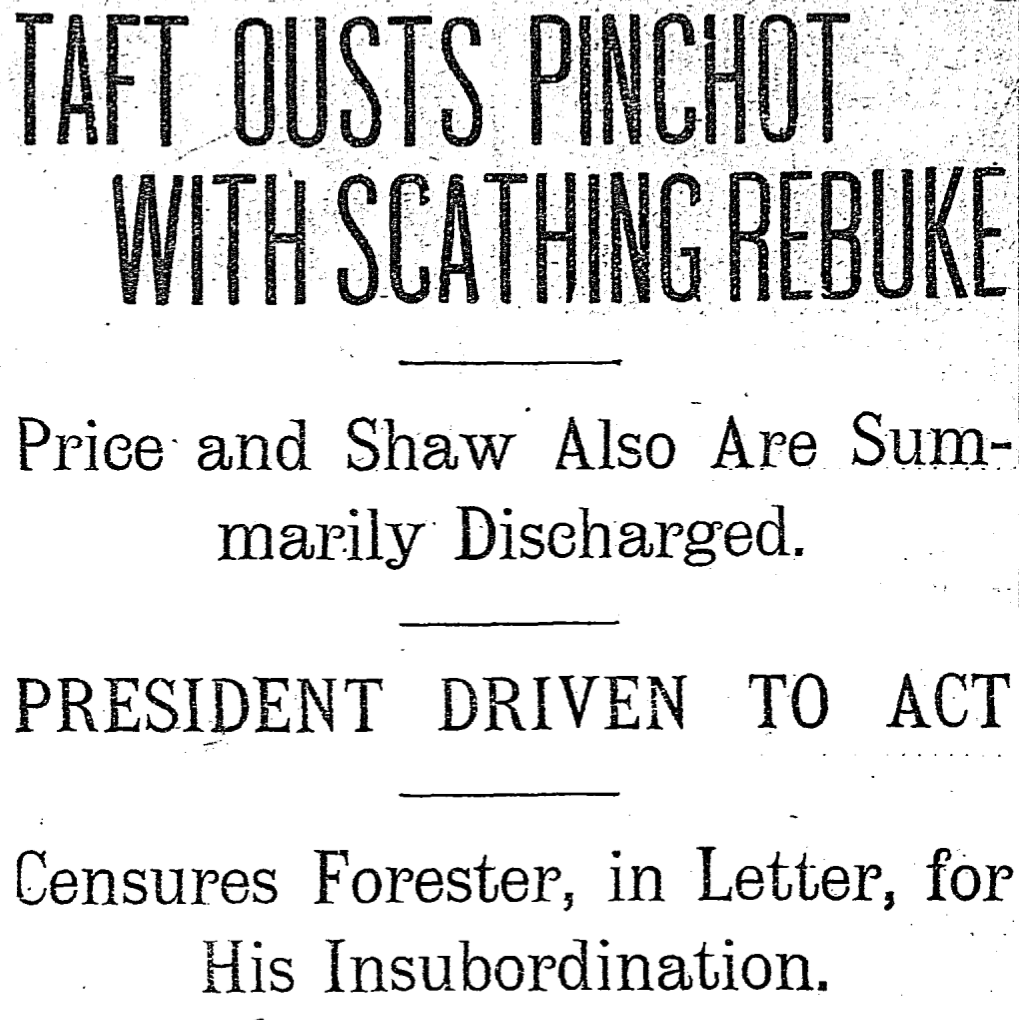

Pinchot, the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service, was a founding father of modern conservation policy—and a major thorn in President Taft’s side. Appointed to the Forest Service in 1905 by President Theodore Roosevelt, he continued in office for the first year of Taft’s term. But once Taft replaced Secretary of the Interior James Garfield, who was also a TR appointee, all hell broke loose. Pinchot waged war against the new Secretary, James Ballinger, largely through leaks to the press denouncing Ballinger as an enemy of conservation and a tool of the trusts. By January 1910, Taft had finally had enough, and he fired Pinchot. And that event, making front-page headlines nationwide, marked the beginning of the end of Taft’s presidency, for it inflamed the “Insurgent” Republicans against Taft and spurred TR to undertake the “Bull Moose” presidential campaign that ultimately thwarted Taft’s bid for re-election.

Surely the Pinchot debacle was not far from Taft’s mind when he wrote Myers. Indeed, the majority opinion’s most memorable rhetoric loudly echoes Taft’s letter firing Pinchot. As Chief Justice, Taft would write:

Each head of a department is and must be the President’s alter ego in the matters of that department where the President is required by law to exercise authority … He must place in each member of his official family, and his chief executive subordinates, implicit faith. The moment that he loses confidence in the intelligence, ability, judgment or loyalty of any one of them, he must have the power to remove him without delay.

Fifteen years earlier, President Taft’s January 8, 1910 letter to Pinchot (republished in full by the Washington Post) ended on a similar note:

… When the people of the United States elected me President they placed me in an office of the highest dignity, and charged me with the duty of maintaining that dignity and the proper respect for the office on the part of my subordinates. Moreover, if I were to pass over this matter in silence it would be demoralizing to the discipline of the executive branch of the government.

By your conduct you have destroyed your usefulness as a helpful subordinate of the government, and it therefore now becomes my duty to direct the Secretary of Agriculture to remove you from your office as the forester. Very sincerely yours, William H. Taft.

The Taft-Pinchot-TR story is an entertaining story for anyone who is interested in the modern history of administration. Pinchot was a character every bit as colorful as the Bull Moose whom he adored. “Gifford Pinchot is a dear,” TR once wrote, “but he is a fanatic.”

But more important for present purposes, the Pinchot affair seems invaluable for fully understanding Taft’s own understanding of the constitutional presidency, as informed by his own experience in that office—in addition to everything already offered by Robert Post in his entertaining and enlightening new article.

Adam J. White is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and director of George Mason University’s C. Boyden Gray Center for the Study of the Administrative State.