Congress’s Anti-Removal Power in Action: The Inspectors General Edition

It’s no secret that today’s Supreme Court is not a fan of Humphrey’s Executor. Especially read together, Free Enterprise Fund, Seila Law, and Collins strongly hint that the Court’s support for Humphrey’s Executor rests on stare decisis alone. Indeed, Seila Law construes Humphrey’s Executor‘s holding so narrowly that — at least if Seila Law is read literally — it is debatable whether Humphrey’s Executor even protects today’s Federal Trade Commission, let alone other independent agencies.

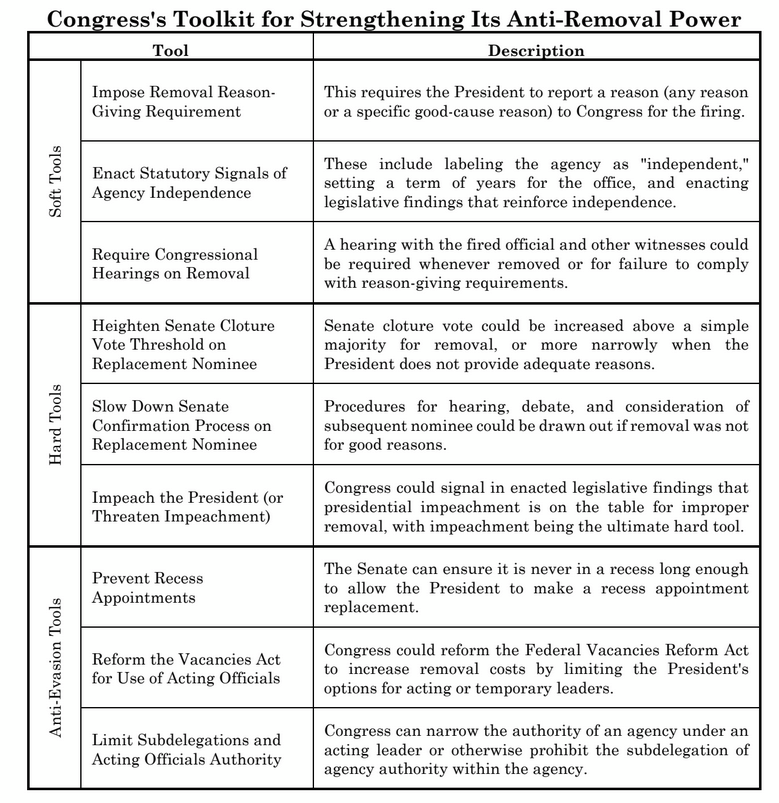

Whatever one thinks of Humphrey’s Executor, however, Congress has other ways to provide agencies with a measure of policy independence — so long as Congress is willing to bear the political heat for using its anti-removal tools. As I’ve explained here before:

Both Alexander Hamilton and James Madison recognized that the Constitution empowers Congress to discourage the president from using his removal authority. For example, Hamilton observed that because the Senate can reject a replacement nominee, a rational president must be careful before pulling the trigger. And even while condemning statutory restrictions on removal, Madison agreed that Congress can make removal so costly that no rational president would exercise the power without a good reason.

These tools include refusing to confirm a replacement official (per Hamilton) or helping the removed official make the President’s life politically difficult (per Madison). Although these tools may not always be as effective as a statutory removal restriction, in many cases — especially for lower profile positions — they should work pretty well.*

In Congress’s Anti-Removal Power (forthcoming very shortly in the Vanderbilt Law Review), Chris Walker and I explain the history of these tools, explain why they work, and collect them in one place:

One common response to the idea that Congress can create policy independence through these tools is that it just isn’t realistic — especially today — to expect Congress to actually do it. Congress, the theory goes, is just too polarized for this idea to be anything more than a thought experiment.

Last month, however, Congress demonstrated that its anti-removal power still has punch today.

In the National Defense Authorization Act, Congress amended various laws regarding inspectors general to make it more costly for the White House to remove them, even without barring removal. Bob Bauer and Jack Goldsmith helpfully explain these changes here:

First, the new law amends Section 3(b) of the Inspector General Act to require the president to notify Congress 30 days prior to removal of an inspector general not just with “reasons,” as before, but with the “substantive rationale, including detailed and case-specific reasons” for removal. This provision does not restrict the grounds on which the president can remove but, rather, requires the president to explain in more detail the reasons for removal. This reform by itself should have little if any impact on the removal of inspectors general. But it could give Congress more information about the removal that would better enable Congress to examine and respond to the removal as it wishes (especially when combined with related adjustments in the new law).

Second, the new law deals with the “administrative leave” gambit for circumventing the 30-day notice. It requires the president, with some exceptions, to communicate in writing to Congress 15 days before changing the inspector general to “non-duty status” (that is, administrative leave) and to supply the “substantive rationale, including detailed and case-specific reasons” for the change in status. It also provides that a president may not place an inspector general on “non-duty status” during the 30 days prior to removal unless the president determines that (and explains to Congress why) the inspector general poses a workplace threat. These (and related) procedural and substantive restrictions should go a long way toward stopping the president from circumventing the 30-day notice requirement on removal via administrative leave.

Third, and most importantly, the new law narrows the president’s options under the FVRA [Federal Vacancies Reform Act] for replacing an inspector general who “dies, resigns, or is otherwise unable to perform the functions and duties of the office.” The new law specifies that a newly defined “first assistant” to the inspector general will fill the vacant inspector general office unless the president directs any “officer or employee” of any office of inspector general, at the GS-15 level or higher, who was in office for more than 90 days before the vacancy (or who is already an inspector general), to perform in an acting capacity. This last provision might seem to allow the president to put a crony in an inspector general office 90 days before firing the inspector general and then appoint the crony in an acting capacity. However, the president cannot easily do this. Everyone in an executive branch inspector general office, other than the inspector general, is a career Title 5 employee and would need to be in the office via a nonpolitical hiring process. The new law thus operates as a deterrent to opportunistic presidential firings of inspectors general by making it very hard for the president to replace the fired inspector general with an ally.

Fourth, the new law specifies that a president who fails to nominate an inspector general within 210 days after a vacancy occurs, or a nomination fails, must explain to Congress the reasons for the delay and provide a target date for making a formal nomination.

I don’t agree with everything Bauer and Goldsmith say. Most notably, they state that the old law — which allowed the President to remove an inspector general for any reason — “proved to be the lowest of bars.” It’s of course true that some inspectors general have been removed (their point), but it is remarkable to me how many have been retained, even when a new administration comes into power. Under the Court’s recent precedent, the administrative leave fix may also raise separation-of-powers concerns.

Regardless, this law illustrates how Congress can create more independence without barring presidential removal. This statement in particular jumps out at me: “The new law thus operates as a deterrent to opportunistic presidential firings of inspectors general by making it very hard for the president to replace the fired inspector general with an ally.” That’s Congress’s anti-removal power in action.

* Suffice it to say, just because Congress can use its power doesn’t mean it always should. As a policy matter, it often makes great sense to allow the President to freely remove. More modestly, our point — which echoes Madison’s and Hamilton’s analysis — is that these tools exist.