D.C. Circuit Review – Reviewed: A (Baker’s) Dozen Thoughts on the D.C. Circuit

It’s great that D.C. Circuit Review – Reviewed is now a team effort. One downside, though, is that I don’t blog every week. This means that when lots of things are happening, ideas start to accumulate. Well, it is my turn to write, so here are 13 thoughts on the D.C. Circuit.

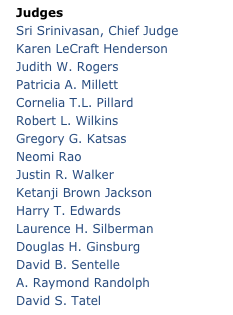

1. We all knew it was coming, but Judge Tatel took senior status this week. His name is now at the bottom of the Court’s seniority list. That will take some getting used to.

2. By the way, that seniority list will be updated pretty soon — I hear Judge Jackson has a new job lined up. And presumably Judge Childs soon will, too.

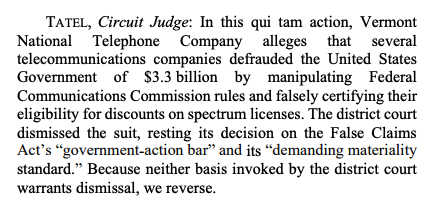

3. Speaking of Judge Tatel, he authored an important qui tam opinion (joined by Judges Rogers and Pillard) this week. From the opinion (USA, ex rel. Vermont National Telephone Company v. Northstar Spectrum, LLC), we see that Jeff Lamken argued against Seth Waxman, and that other legal heavyweights were on the respective briefs. Here is the opening paragraph:

If you follow telecommunications law or qui tam litigation, definitely read this one. The discussion of the meaning of the phrase “administrative civil money penalty proceeding” on pages 8 to 11 is especially interesting. Given the vast amount of money at issue, I would not be surprised to see a cert petition, even though the case is in an interlocutory posture.

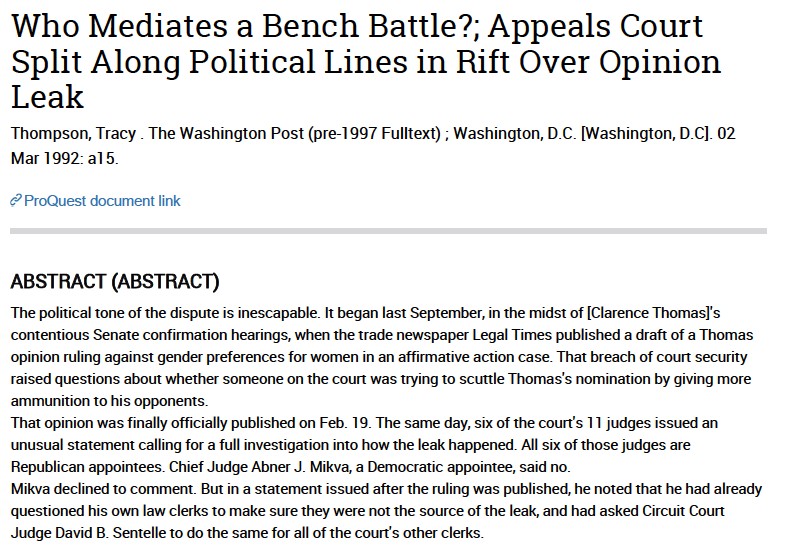

4. Josh Blackman wrote a post at Volokh a couple of weeks ago about a leak from the D.C. Circuit. It seems that in 1991, someone leaked details of a D.C. Circuit opinion to the Legal Times, which prompted Judge Buckley to call for “the Court to initiate a formal investigation in an effort to identify the source or sources of this disclosure.” With the help of the good folks in BYU Law’s library, I’ve done a bit more research into the matter and found this story from the Washington Post in March 1992:

The story has some eyebrow-raising sentences, including:

- “The political tone of the dispute is inescapable. It began last September, in the midst of Thomas’s contentious Senate confirmation hearings, when the trade newspaper Legal Times published a draft of a Thomas opinion ruling against gender preferences for women in an affirmative action case. That breach of court security raised questions about whether someone on the court was trying to scuttle Thomas’s nomination by giving more ammunition to his opponents.”

- “‘This is not going to be the end of it,’ said one federal district judge, who did not want his name used. ‘I don’t understand Abner at all, I really don’t. You would think it’s normally better to clear the air. . . . It’s unusual that when a majority of the court votes for something, that has no effect on the outcome.'”

- “The D.C. Circuit is traditionally the most politicized of all the federal appeals courts, and brawls among its members are hardly unprecedented. In the 1970s, then-Chief Judge David L. Bazelon and Warren Burger, later chief justice, were frequent and vociferous critics of each others’ views.”

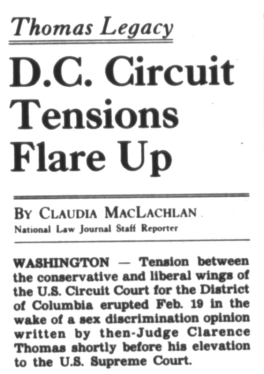

There is also this story from the National Law Journal:

It includes some more details:

- “Judge Mikva said the results of an informal inquiry he ordered right after the leak revealed that Justice Thomas’ own law clerks had given the majority and dissenting drafting opinions broader circulation than normal. ‘While this deviation from our usual procedures did not … violate ethical strictures, it did enormously increase the universe of persons who had access,’ he said.”

- “Later in the day, Circuit Judge Laurence H. Silberman, one of the judges calling for an investigation, issued his own statement, saying Judge Mikva’s explanation was misleading: ‘Now that he has opened up the subject, he should disclose the full truth of the court’s decision-making process on this terribly serious matter,’ he said.”

And then there is this remarkable judicial decision (from the Western District of Washington, revising a footnote from a previous decision of the court) that discussed the D.C. Circuit’s incident in great detail:

The memorandum which follows was initially entered on April 19, 1991. Trial judges on occasion are tempted to publish dated opinions when authority later issues supporting their views; viz., the I-wrote-it-first syndrome. Publication in this case has been prompted by a quite contrary consideration. Research in connection with another case revealed Lamprecht v. F.C.C., 958 F.2d 382 (D.C. Cir. 1992). Lamprecht establishes conclusively that footnote 4 herein [which states, among other things, that “the Court is aware of no published decision involving the commission of a corrupt act by a law clerk”] is dead wrong. It was not in April of 1991, but it is now. Some might question burdening the Federal Supplement with material known to be flawed, but the purpose of doing so should become apparent in due course.

Whatever one might think of the merits of the controversy swirling around Justice Thomas and his confirmation hearing, few fair-minded observers would disagree with the proposition that the circus atmosphere cheapened the process by which individuals are selected to serve as the final arbiters of the law. Beyond the process itself, some of the participants therein, and the Supreme Court as an institution, there was yet another casualty.

Among the potholes in the road to confirmation was then-Judge Thomas’ involvement in a controversial and emotionally charged appeal challenging FCC policy in favoring female applicants for broadcast licenses. The policy would ultimately be struck down on equal protection grounds. The merits of the decision are of no moment to this discussion, but the procedure which attended it is. The case was argued in January of 1991 and remained under submission during the confirmation hearing. Chief Judge Mikva and Judges Thomas and Buckley already knew what the outcome would be and preliminary drafts of the disposition had been circulated among the members of the panel. In keeping with standard practice, no one else outside of the three judges’ immediate staff should have known.

Suddenly, everyone knew when the press reported, with stunning accuracy, what the ruling would be and that Judge Thomas would author it. Judge Buckley makes no bones about who leaked the preliminary drafts. It was one of the twelve law clerks working for the panel members. Not only were the drafts released but an unnamed source employed by the Court opined that the decision was being “delayed by Judge Thomas so as not to imperil his nomination.” The New York Times, Feb. 20, 1992, Section A; Page 1; Column 1. The nomination was already in trouble for reasons too widely publicized to bear reiteration. That Judge Thomas would put his suspected anti-affirmative action views into practice in Lamprecht would not help him in some circles. The accusation that he might delay releasing the opinion to serve political ends was even more damaging.

The scope of possible culprits expanded geometrically when it developed that one of Judge Thomas’ law clerks distributed the preliminary drafts to the chambers of other circuit judges not on the panel. The New York Times, Feb. 21, 1992, Section A; Page 12: Column 5. From there, of course, the drafts could have been further disseminated by any number of individuals affiliated with the D.C. Circuit.

Judge Buckley describes such leakage as a “willful breach of trust” which “cast[s] a shadow” over every law clerk privy to the drafts. So it is, and so it does. The leak could not have been motivated by a well-meaning but empty-headed desire to enlighten the public as to what the law was or would be. The motive, rather, could only have been to defeat Judge Thomas’ nomination. Judge Buckley goes nowhere near far enough in his characterization or condemnation. A law clerk who employs his or her unique privity with the judicial process in an effort to subvert the political process violates the most sacrosanct of canons and is guilty of nothing less than official corruption ….

So viewed, footnote 4 is wrong. With confidence that this sorry episode is an example of the exception proving the rule, the following nineteen-month-old memorandum will be dusted off and submitted for publication.

5. Moving beyond the (shameful) leak at the Supreme Court to the substance of the leaked draft opinion, it seems safe to assume that some on the Supreme Court already have or will soon dust off the following speech from the D.C. Circuit’s own Judge Randolph: Before Roe v. Wade: Judge Friendly’s Draft Abortion Opinion.

6. Pop quiz: “After argument in a case involving street protests directed at the Bush 43 Administration, one member of the panel asked the others if they had ever participated in a protest demonstration. Which judge answered, ‘No, but I have been the target of many’?”

7. The D.C. Circuit doesn’t get a lot of antitrust litigation, but it gets some. This week it decided another one: In re: Rail Freight Fuel Surcharge Antitrust Litigation. (If you are interested, this oral argument featured Don Verrilli v. Kathleen Sullivan.) Judge Edwards — joined by Judges Millett and Tatel — addressed 49 U.S.C. § 10706(a)(3)(B)(ii)(II), which provides that “[i]n any proceeding in which it is alleged that a carrier was a party to an agreement, conspiracy, or combination in violation of [certain federal laws, including the Sherman Act] … evidence of a discussion or agreement … shall not be admissible if the discussion or agreement … concerned an interline movement of the rail carrier, and the discussion or agreement would not, considered by itself, violate the laws referred to in the first sentence of this clause.”

So what is an “interline movement”? Well, they are “shipments carried along two or more railroads’ tracks under a common arrangement.” But what is a discussion or agreement that concerns an interline movement? Take it away, Judge Edwards:

We hold that a discussion or agreement “concern[s] an interline movement” only if Defendants meet their burden of showing that the movements at issue are the participating rail carriers’ shared interline traffic. A discussion or agreement need not identify a specific shipper, shipments, or destinations to qualify for exclusion; more general discussions or agreements may suffice. For example, evidence of a discussion or agreement about policies applicable to all of the participating railroads’ shared interline traffic is excludable under Section 10706, provided the evidence satisfies the statute’s other requirements and the court can identify the movements at issue as the carriers’ shared interline traffic. The same is true of discussions or agreements about the formation of the participating railroads’ interline agreements, as well as about their anticipated shared traffic. A single document may reference more than one discussion or agreement. … Consistent with the foregoing interpretation of the statute, evidence of discussions or agreements about single-line traffic or about freight traffic generally is not excludable under Section 10706.

8. The FTC again has five commissioners. FTC rulemaking — and then fierce litigation about FTC rulemaking — presumably comes next. Truth on the Market recently hosted an online symposium on the issue. The key case is the D.C. Circuit’s National Petroleum Refiners Association v. FTC — a 1973 case that will soon be read carefully by lots of lawyers. In my contribution to the symposium, I discuss what may happen to the FTC as an institution if the agency becomes a serious rulemaker. (If you’re interested, here is a book chapter I wrote the subject and here is a recent op-ed of mine that strikes me as relevant.)

9. The D.C. Circuit gets a lot of high profile FOIA cases. Here’s another: Campaign Legal Center v. DOJ. Here is how Judge Millett (joined by Judges Katsas and Rao) opened her opinion:

The district court concluded that “responsive drafts of the Gary Letter and associated emails could not be withheld because they were completed after the Attorney General had already decided to request the citizenship question,” but the D.C. Circuit disagreed (in part): “The process of drafting the Gary Letter to request the addition of a citizenship question in a way that protected the Department’s litigation and policy interests involved the exercise of policymaking discretion, and so the letter’s content itself was a relevant final decision for purposes of FOIA’s deliberative process privilege.” Here is the key analysis: “substantive judgment calls made in the process of drafting and editing a formal agency document that first communicates a policy decision can themselves embody distinct policy determinations, especially when the content of that communication itself shapes and sharpens the underlying policy judgment or will have direct consequences for ongoing agency programs and policies.” That said, the Court remanded for five emails because the record regarding them is unclear.

10. Marino v. NOAA presents an interesting standing puzzle. Here is how Judge Ginsburg (joined by Judges Henderson and Katsas) opened his opinion:

Here’s the situation. The NMFS can issue permits exempting certain actions from the federal bar on “taking” covered marine mammals, including for public display — which “includes placing marine mammals in facilities such as SeaWorld’s marine zoological parks in Orlando and San Diego.” The NMFS used to enforce compliance with those permits and required displayers to provide an animal’s medical data to the agency, but, following a 1994 law, says that now the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service in the U.S. Department of Agriculture is responsible for compliance. The plaintiffs disagree with that interpretation. After a whale died, the plaintiffs asked the NMFS to enforce the permit and have SeaWorld provide the data; the NMFS essentially said “nope” on the theory that it lacked enforcement authority. The plaintiffs then sued.

According to the Court, the plaintiffs lack standing because they “have failed to allege [that] a favorable decision here would lead the NMFS to enforce the permit conditions and thus redress their alleged injury.” After all, says the Court, the NMFS would have discretion even under the plaintiffs’ theory, and it is too speculative that the agency would use that discretion in a way the plaintiffs want. Indeed, “[t]hey did not allege, even on information and belief, that the NMFS was likely to enforce the terms of the permit against SeaWorld ….” (The Court also said that SeaWorld may not have complied with such a request even if it were made because plaintiffs “do not allege SeaWorld ever created and still retains the reports the plaintiffs seek.”)

As Daniel Hemel and I explained in Chevron Step One-and-a-Half, agencies sometimes claim that they don’t have discretion when they really do; under the D.C. Circuit’s Prill v. NLRB line of cases, an agency’s failure to correctly understand the scope of its authority is itself error. For standing purposes, however, it now appears that where a private person affirmatively wants the agency to do something and the agency says it lacks authority to do it, it is not enough to say that the agency is wrong about the law — the private person also must allege that if the agency properly understood the law, it is “likely” that the agency would use its discretion as the private person wishes. Interesting. Going forward, plaintiffs should scour agency statements and the like for evidence upon which to allege — “on information and belief” — that the agency really wants to do what the plaintiff wishes and that it would do so but for its mistake about the law. (Thanks Asher Steinberg for flagging the Prill issue.)

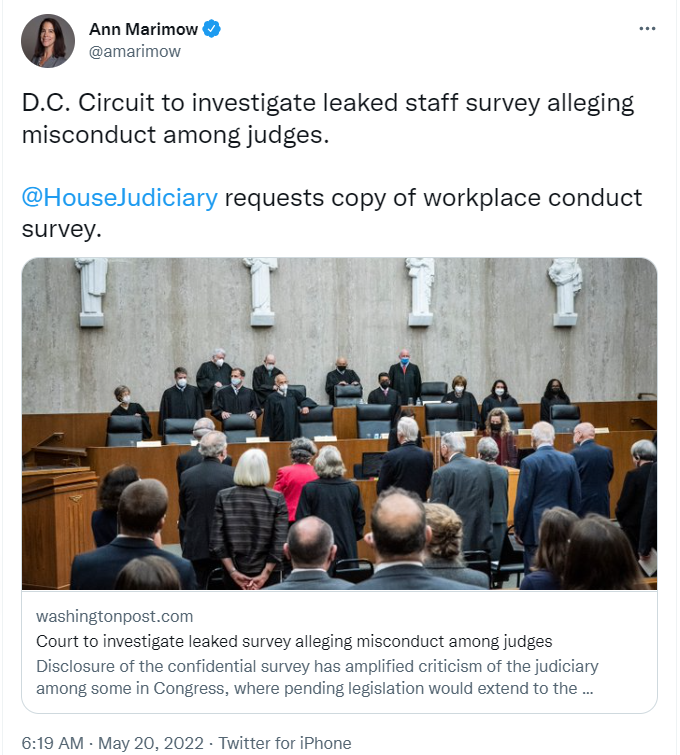

11. On the subject of the Washington Post (see number 4, supra), here is a story from this week: Judges Accused of Sex Discrimination, Bullying, Internal Survey Shows. It appears that someone sent the Post a copy of a “confidential workplace survey” and that various individuals have spoken about it. It also looks like there will be “mandatory courthouse-wide training this month, including for the court’s 40 judges.” (What does “mandatory” mean though for Article III judges?)

Plus this:

12. If you’re a Fed Courts person, check out Dufur v. U.S. Parole Commission. Judge Rogers (joined by Judge Pillard) concluded that a suit by a prisoner in prison for murder against the U.S. Parole Commission was not barred but did fail on the merits; Judge Randolph concluded it was barred because the only path to relief is through habeas (indeed, he says the majority opinion has turned “upside down, inside out and back to front” would should have been a “rather straightforward appeal”). The procedural history of this case is messy. But if you want to read a case forfeiture, jurisdiction, and the rules of habeas, this one is for you.

13. Judge Janice Rogers Brown (ret.) — for whom I clerked — did a public event on the First Amendment this week at the American Enterprise Institute. If you are interested in what Judge Brown had to say (and she has a knack for saying interesting things), here is a link to the recording.

* And sometimes becomes more than a little stale ….

D.C. Circuit Review – Reviewed is designed to help you keep track of the nation’s “second most important court” in just five minutes a week.