D.C. Circuit Review – Reviewed: More Chevron Waiver

About a year ago I wrote a post entitled “Chevron Waiver.” Here is the gist of it:

So the Court, this week, wasn’t that busy. Which is good, because it gives me time to elaborate on an issue that came up last week: Chevron waiver. I promised to discuss recent scholarship on the topic. Well, here are three recent articles worth reading: James Durling & E. Garrett West, May Chevron Be Waived?, 71 Stan. L. Rev. Online 183 (2019); Note, Waiving Chevron Deference, 132 Harv. L. Rev. 1520 (2019); and Jeremy D. Rozansky, Waiving Chevron, 85 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1927 (2018). They all reject Chevron waiver; as they see it, an agency’s failure to argue for deference during litigation should not stop a court from deferring. (This is different from Chevron Step One-and-a-Half, where the agency did not acknowledge ambiguity during the regulatory process itself.)

Taking Chevron on its own terms, I think their analysis is mostly right (for what it is worth, I reviewed drafts, but the ideas are entirely the authors’). But I’m not sure it is always right. I’m still working through a theory of waiver. But — and I’m just thinking out loud here — I can imagine situations where a reviewing court, in its discretion, should be able to decline to do the work of the litigants, even when it comes to legal interpretation. That is, at least if the decision does not preclude another party from later advancing the correct interpretation. If, say, it would take a great deal of independent research (be it historical, linguistical, or contextual) to figure out the right answer to an interpretative question, and spending the time to research the issue may cause other cases on the docket to fall behind (for instance, criminal cases), then, depending on our theory of waiver, perhaps waiver/forfeiture may be appropriate “sanction” against the relevant party for offloading that work onto the court. To be sure, I don’t think a court should be required to stay within the four corners of the parties’ briefs when it comes to questions of interpretation. But is it really the case that a court is never even allowed to do so, no matter what? And how do burdens fit into this? And what about appellate review (at least where the agency is the appellant, and so may have a greater burden) versus direct review? Maybe Chevron, moreover, is different because it is never hard for the court to identify ambiguity? But is that right? We don’t even have a standard theory of ambiguity.

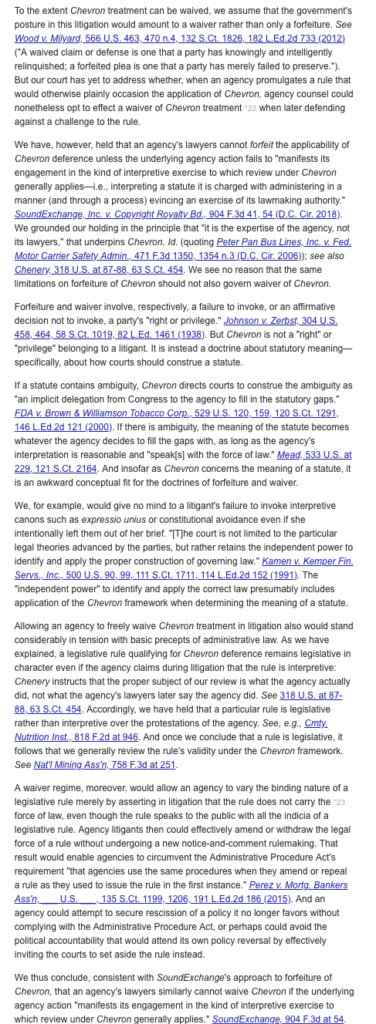

Since then, the D.C. Circuit pointedly rejected Chevron Waiver (or at least a species of it):

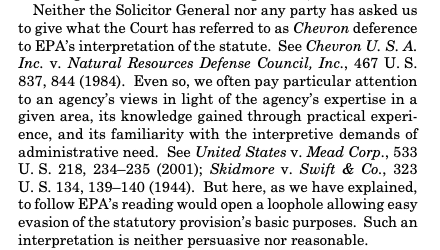

But did this law just change yesterday?* Here is a quote from Justice Breyer’s opinion for the Supreme Court in County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund:

Did the Supreme Court just hold that Skidmore, rather than Chevron, applies when agency counsel doesn’t argue for deference? The Court didn’t defer, but it did apply Skidmore. Sure, there are some reasons to think that this isn’t a holding. Chevron doesn’t apply to interpretative statements to begin with (counterargument; that isn’t the reason the Supreme Court gave not to apply Chevron). This issue wasn’t briefed (counterargument; no one briefed overruling Swift v. Tyson but we still refer to the Erie doctrine). This is just a short paragraph (counterargument: a key portion of the Supreme Court’s discussion of the likelihood of success in Winter v. NRDC, Inc. is also short). Finally, allowing waiver would be bad for all the reasons the D.C. Circuit said (counterargument: well, that isn’t how Supreme Court review works and, in any event, it might not always be that bad).

I’m sure there are other arguments (and counterarguments). Mine are just very quick reactions. Let’s see what the D.C. Circuit says next.

***

The D.C. Circuit decided a number of cases this week. Unfortunately, the Court’s website is down:

I can’t link to the Court’s decisions (well, at least not directly, I’ve done by best to find them via google). Even so, here is a quick rundown — with thanks to my excellent RAs who have read the decisions in full.

It was a bad week for the EPA. Judge Pilard, joined by Judge Henderson, wrote for the Court in Louisiana Environmental Action v. EPA. Judge Sentelle dissented. Very, very short version: Does EPA have a duty to address pollutants that are listed as hazardous but not yet controlled by any emission standard? Yes. In Hall & Associates v. EPA, Judge Millett (joined by Judges Henderson and Griffith) concluded that when EPA made a nonacquiescence decision was a genuine issue of disputed material fact for purposes of FOIA’s applicability. In Physicians for Social Responsibility v. Wheeler, Judge Tatel (joined by Judges Rogers and Tatel) held that a 2017 EPA directive that prohibits any grant recipients from serving on advisory committees was arbitrary and capricious because it failed to adequately justify its change in policy. Moving beyond environmental law, in Stewart v. Modly, a per curiam panel (Judges Tatel, Pillard, and Edwards) rejected the argument that the Navy should have waived certain statutory requirements. And in United States v. Abney, Judge Pillard (joined by Chief Judge Srinivasan and Judge Tatel) held that the district court erred by not allowing a defendant to speak before imposing a sentence but denied a request that the case be assigned to a different district court judge.

That is the week (now I’m going to start grading exams).

UPDATE: The webpage is now working. I’ve added links to the cases.

* David Zaring and Kristin Hickman had an interesting conversation on Twitter about this.

D.C. Circuit Review – Reviewed is designed to help you keep track of the nation’s “second most important court” in just five minutes a week.