DC Circuit Review – Reviewed: Administrative Law Without The Administrative Procedure Act

Sorry; this post is quick — I’ve been traveling today and am about to hop on a flight.

The big D.C. Circuit news today this week this month this year this presidential term is, of course, this:

We have written about Judge Jackson before here at Notice & Comment, including Aimee Brown’s post from earlier this week. I suspect more posts in the future.

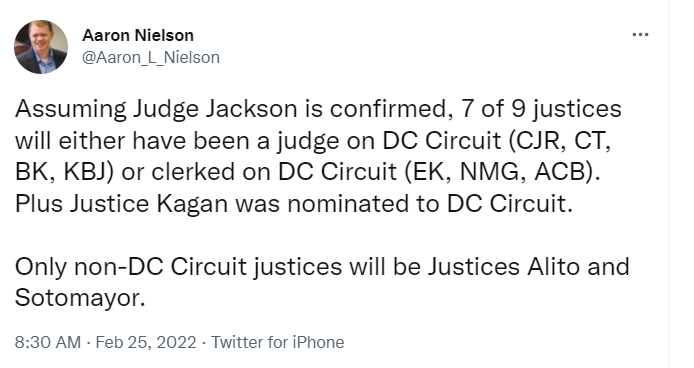

One quick observation. For good or ill, the D.C. Circuit’s capture of the Supreme Court is almost complete:

There may be more posts on that subject, too.

This week, however, I want to discuss the D.C. Circuit’s approach to administrative law without the Administrative Procedure Act. The Court’s two “admin law” cases this week* fall into this category.

First, consider National Association of Postal Supervisors v. USPS. Congress has declared that the Post Service isn’t subject to the APA, but it still has to comply with various statutory requirements. The D.C. Circuit ensures that it does so under “ultra vires” review. What’s that? Well, here is Judge Edwards’ (cleaned-up, citations and quotations omitted) explanation, joined by Judges Pillard and Wilkins:

The case law in this circuit is clear that judicial review is available when an agency acts ultra vires, or outside of the authority Congress granted. Review for ultra vires acts rests on the longstanding principle that if an agency action is unauthorized by the statute under which the agency assumes to act, the agency has violated the law and the courts generally have jurisdiction to grant relief.

Additionally (and this is something I didn’t know), at least in the D.C. Circuit, “ultra vires” review includes the Chenery I doctrine:

Under ultra vires review, a statutory construction by an agency is impermissible if it is utterly unreasonable. We owe a measure of deference to the agency’s own construction of its organic statute, but the ultimate responsibility for determining the bounds of administrative discretion is judicial. Moreover, an agency acts ultra vires when its decision is not supported by a contemporaneous justification by the agency itself, but only a post hoc explanation by counsel.

Candidly, that inclusion surprised me because I haven’t thought of Chenery I as a limit on an agency’s statutory authority, as opposed to a procedural requirement for the agency to explain itself. After all, if agency does X without an explanation, the Court may require that explanation before upholding the agency action, but if the agency turns around and provides such an explanation, the Court may very well conclude that the agency can do X (indeed, that is what happened in Chenery II). If the agency action — so long as it is properly explained — is lawful, it seems a bit odd to say that the agency acted outside of its statutory authority rather than simply inadequately explained its decision. That said, Chenery I may not be an ordinary procedural rule; Kevin Stack has even argued that it is has constitutional weight. Hmm. This is something I need to think more about. (Perhaps a law student looking for a note idea could ask when ultra vires review itself becomes ultra vires!)

Anyway, in this week’s case, the Court concluded as follows:

After carefully reviewing the record in this case, and applying controlling principles from National Association and its progeny, we hold that the Association has plausibly alleged that the Postal Service exceeded its statutory authority and failed to act in conformance with the commands of the Act in the following respects: First, the Postal Service acted ultra vires by failing to institute “some differential” in pay for supervisors and by failing to demonstrate that it set its compensation levels by reference, inter alia, to the compensation paid in the private sector. Second, the Postal Service failed to follow the commands of the Act by refusing to consult with the Association on compensation for “Area” and “Headquarters” employees; by refusing to consult regarding postmasters; and by failing to provide the Association with reasons for rejecting its recommendations. Accordingly, we reverse the judgment of the District Court and remand for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

The second case is In re: NTE Connecticut, LLC. Here, Judge Rao (joined by Judge Jackson, with Judge Wilkins dissenting) issued a opinion that relied on the Court’s All Writs Act authority:

Petitioner NTE Connecticut, LLC (“NTE”) acquired valuable authorization to sell electricity from its new power plant. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (“FERC”) revoked that authorization and, in so doing, very likely fell short of its obligation under the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) to explain the reason for its decision. Absent emergency relief from this court, FERC’s order would have irreparably harmed NTE, preventing it from participating in a February 7, 2022, auction to sell future electricity capacity to New England consumers. On February 4, 2022, we granted NTE’s petition for an emergency stay of FERC’s order, with an opinion to follow. This is that opinion.

Here is Judge Rao’s explanation for this authority (again, without citations and the like):

The All Writs Act gives this court the power to issue all writs necessary or appropriate in aid of its jurisdiction. In an ordinary FERC case, we have jurisdiction only after the agency issues a final order on rehearing, or after thirty days have lapsed from a party’s application for rehearing. But this court has an inherent power under the All Writs Act to stay agency action in order to preserve its prospective jurisdiction.

I also thought this footnote was interesting:

This court has characterized various requests for relief under the All Writs Act as petitions for mandamus, and our order granting NTE’s petition reflected that practice. Strictly speaking, however, NTE has not asked for a writ of mandamus—it does not ask us to compel FERC to take some action—but for a stay of FERC’s order to preserve the status quo. As explained above, when a party requests a stay under the All Writs Act and the statutorily prescribed remedy is clearly inadequate, we evaluate the petition for relief like an ordinary application for a stay. To avoid confusion, with the publication of this opinion we also revise the February 4 order to remove the reference to mandamus and to clarify that we granted an emergency petition for a stay pursuant to the All Writs Act.

Using this authority, the majority concluded that FERC had not adequately explained itself and that emergency relief was warranted. In dissent, Judge Wilkins disagreed.

* The final case this week isn’t an administrative law case at all. In Leonard A. Sacks & Associates v. International Monetary Fund, Judge Pillard (joined by Judges Henderson and Silberman) opened her opinion this way:

Plaintiff Leonard A. Sacks & Associates, P.C. (Sacks) sued the International Monetary Fund (Fund or IMF) to modify or vacate an arbitration award it obtained against the Fund. The Fund asserted its immunity, and the district court dismissed the case. Sacks does not dispute the Fund’s general entitlement to immunity under its Articles of Agreement, which have legally binding effect in the United States pursuant to the Bretton Woods Agreements Act (Bretton Woods Act). But Sacks claims that, by including in the parties’ contract an agreement to arbitrate under the rules of the American Arbitration Association (AAA) and the laws of the District of Columbia, the Fund effected a limited waiver of that immunity to allow judicial enforcement, modification, or vacatur of any resulting arbitration award. Sacks’ argument makes good sense: Both the AAA Rules and D.C. law contemplate judicial involvement in the enforcement of arbitral awards, so arguably the contract does as well. But a waiver of the immunity of an international organization must be explicit. Because the Fund’s contract with Sacks expressly retains the Fund’s immunity, reiterating it even within the arbitration clause itself, we affirm.

D.C. Circuit Review – Reviewed is designed to help you keep track of the nation’s “second most important court” in just five minutes a week.