DC Circuit Review – Reviewed: Cases with Controversies

It was quite a week for hot-button issues in Washington, D.C. During the same week that the U.S. Supreme Court resolved two petitions in cases challenging S.B. 8—the Texas law prohibiting abortions after about six weeks—the D.C. Circuit decided cases touching on January 6, the travel ban, a mask mandate, and, of course, Entergy Arkansas’ off-system excess energy sales. The decisions do nothing to bring an end to these controversies (except, it is hoped, the energy sales), but they work at the margins in an effort to ensure that the public debate about them proceeds in the proper fora, and with the proper information. Whether they succeed, I will leave it to readers to judge.

The headline decision is Trump v. Thompson, which resolved President Trump’s emergency appeal seeking to stop the disclosure of certain documents over which he has asserted executive privilege. The United States House Select Committee To Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol subpoenaed the documents as part of its investigation into the events of January 6. I commend the opinion (by Judge Millett, joined by Judges Wilkins and Jackson) to readers for a detailed background on the history of presidential papers and the legal rules governing Congress’ access to them. Both Congress’ power to demand the President’s papers and the President’s privilege to withhold them are unwritten but implicit in the Constitution. Congress may subpoena official documents related to and in furtherance of its legitimate functions, and the President may withhold documents that reflect his decision-making and deliberations if he believes they should be kept confidential. The privilege must, however, give way in the face of “a strong showing of need” by Congress.

Courts dislike resolving disputes between the political branches, and more often than not, the President and Congress “hash[] out” their differences over congressional subpoenas “in the hurly-burly, the give-and-take of the political process.” In this case, politically aligned President Biden and Congress reached an agreement about which papers the Administration would turn over to the House Select Committee, but former President Trump (whose Administration generated the papers) objected. I was surprised to learn that, until the 1970s, “Presidents exercised complete dominion and control over their presidential papers after leaving office.” The Watergate scandal changed this practice, as it did many things, by prompting Congress to assert U.S. ownership over official presidential records.

The Supreme Court has since held that former presidents retain a right to assert executive privilege over official documents generated during their administrations, and legislation and regulations give former presidents a role in the incumbent administration’s response to congressional subpoenas seeking these documents. The privilege is a unitary one, however: it is “for the benefit of the Republic” and not for the benefit of either the incumbent or the former Presidents as individuals. The novel question presented by this case is: what happens when the two people entitled to assert the privilege disagree about what is best for the Republic?

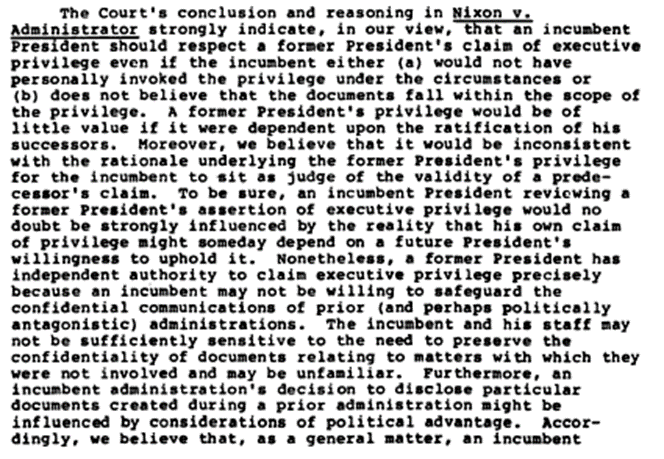

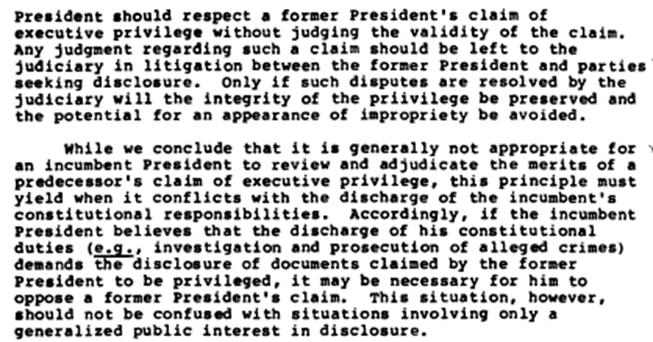

The Office of Legal Counsel has opined that an incumbent President “should” respect a former President’s privilege assertions unless the discharge of his constitutional duties demands their disclosure:

The D.C. Circuit, however, has opined that respect is not constitutionally compelled.

Ultimately, the Court declined to enunciate a standard for adjudicating a dispute between incumbent and former Presidents or even to decide whether it would adjudicate such disputes in the future (instead of allowing the incumbent’s decision to stand by default). Instead, it concluded that under any standard it might adopt, President Trump’s challenge does not succeed: President Biden and Congress made considered decisions in favor of disclosure, and more importantly, those decisions align. “A court would be hard-pressed under these circumstances to tell the President that he has miscalculated the interests of the United States, and to start an interbranch conflict that the President and Congress have averted.”

In the interest of keeping this post within the range of a five-minute read, I will leave it to readers to peruse the details of the Court’s analysis. President Trump also challenged the subpoena on the ground that it lacks a valid legislative purpose, arguing that the asserted purposes are pretextual and cover a law enforcement objective beyond the scope of Congress’ powers: namely, trying him for his actions leading up to and on January 6. The Court rejected his arguments. The Court also entered an administrative stay to give President Trump time to seek interim relief and a writ of certiorari from the U.S. Supreme Court. One final note: curiously, the Court did not address the jurisdictional question that it raised sua sponte a week before argument, which Aimee helpfully describes here.

Judicial Watch, Inc. v. U.S. DOJ reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment to the government in a FOIA lawsuit. The suit sought four documents sent to or from the email account of then-Acting Attorney General Sally Yates on the day she issued a statement announcing that DOJ would not defend President Trump’s so-called “travel ban”: an executive order temporarily suspending entry by foreign nationals of countries judged to present heightened terrorism threats. Relying on a declaration that identified the documents as working drafts, the district court held that the government properly withheld them under the deliberative process privilege. In a relatively brief opinion that extolls FOIA’s contribution to securing an “informed citizenry” in our “democratic society,” Judge Tatel (joined by Judges Henderson and Wilkins) held that drafts are not categorically deliberative, and that DOJ failed to provide enough information to establish that these drafts were. The Court remanded with instructions for the district court to conduct an in camera review.

In Corbett v. TSA, a pro se petitioner who bills himself as a “professional troublemaker” challenged TSA directives mandating that travelers wear masks. The petitioner is a frequent traveler who wishes to wear his mask less often than the TSA requires. He challenged the directives as beyond TSA’s national security-oriented regulatory authority. Judge Edwards (joined by Judge Tatel) rejected this “extraordinarily narrow” view of TSA’s authority and held that the agency may regulate in response to threats to air travel beyond intentional attack, including public health threats. Judge Henderson in dissent agreed with the majority that “this petition for review is a slam dunk loser,” but she would have dismissed it for lack of standing. She pointed out that the CDC also requires travelers to wear masks. The primary difference between the two agencies’ requirements is that, while both permit travelers to remove masks briefly to eat and drink, TSA requires them to replace the masks between bites and sips. Invoking some of the same authorities as did Justice Thomas in an opinion of the same date, she found petitioner’s injury to be too speculative, generalized, and trifling to support a facial challenge. “De minimis non-curat lex . . . resolves [petitioner’s] annoying waste of judicial resources.” (Judge Henderson’s opinion is fair, but I wonder whether petitioner could have bolstered his standing by averring that he travels frequently with children. The “between bites and sips” rule very effectively thwarts my efforts to exempt my children from in-flight mask mandates with a steady stream of Goldfish crackers, with predictable consequences for my fellow travelers and me.)

Louisiana Public Service Commission v. FERC looks to bring an end to a long-running dispute concerning energy sales that occurred over two decades ago. In 2009, the Louisiana Public Service Commission successfully challenged an Arkansas utility’s excess energy sales under a service agreement among six regional utilities. In the damages phase, FERC determined that a subset of the sales fell outside the scope of its liability determination, prompting the Louisiana Commission to petition for review and to bring a new complaint in 2019. FERC determined that a 2015 settlement agreement barred the new complaint, and the Louisiana Commission petitioned for review of that decision, as well. In a methodical opinion by Judge Sentelle (Judges Henderson and Jackson joining in full), the Court rejected a raft of objections to FERC’s resolutions of the 2009 and 2019 complaints. The Court concluded that substantial evidence supported FERC’s factual determinations and that its rulings were not otherwise arbitrary, capricious, or contrary to law.

The subject matter of the final opinion will garner fewer headlines, but the decision brings to a thoughtful conclusion litigation that has spanned a dozen years and no doubt commanded significant investments by the interested parties. It is perhaps a healthy thing for our republic that we see this concrete controversy end peaceably in the judicial system and can now turn our attention to the political arena to watch the people work out broader disagreements concerning elections, immigration, and public health.

D.C. Circuit Review – Reviewed is designed to help you keep track of the nation’s “second most important court” in just five minutes a week.