DC Circuit Review – Reviewed: Co-opting Cooperation

Last week, the D.C. Circuit resolved four sets of petitions for review and one appeal. Each set of petitions for review models a different form of regulatory cooperation between the government and private entities: a statute that incorporates industry standards, private enforcement of an agency license, agency review of rules promulgated by self-regulatory organizations, and agency supervision of a semi-private contract. The disposition of the appeal, too, presumes a form of cooperation–this time, among private parties.

In American Public Gas Association v. U.S. Department of Energy, the Court remanded, without vacating, a Department of Energy rule setting efficiency standards for “commercial packaged boilers” used to heat commercial and multifamily residential buildings. By statutory default, the Secretary of Energy adopts efficiency standards promulgated by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. But under certain circumstances, the Secretary may adopt a more stringent standard if “she has clear and convincing evidence the more stringent standard is economically justified, technically feasible, and will lead to significant conservation of energy.” The consolidated petitions for review challenged the reasoning supporting the Secretary’s finding that the standard she adopted was “economically justified.” That finding rested on, among other things, a comparison of the “life-cycle costs” of commercial packaged boilers under the default standard and their life-cycle costs under the more stringent standard. Life-cycle costs include the purchase price and the present-value discounted lifetime operating costs. The “[c]onceptual simplicity” of calculating life-cycle costs “belies [its] operational complexity.” Judge Ginsburg (joined by Chief Judge Srinivasan and Judge Jackson) disassembled the operational complexities with characteristic clarity and found in the inner workings of the Department’s analysis questionable assumptions and methodologies that the Department had not adequately explained or defended. The panel remanded the rule to the Department to take “appropriate remedial action” within ninety days.

Several features of the decision will interest D.C. Circuit watchers. The first is the “clear and convincing evidence” standard that the Secretary must apply in deciding whether to exceed default efficiency standards. The Court observed that it is “unusual, perhaps unique” in the world of informal rulemaking: “we are aware of no other authorization for rulemaking subject to this heightened evidentiary standard.” The heightened standard did not, however, affect the stringency of judicial review: “The court asks itself only whether it was reasonable for the agency to determine it met the standard.” The second interesting feature of the decision also relates to the clear and convincing evidence standard. The Department of Energy joined the petitioners in arguing that it had failed to apply the appropriate standard, yet the Court “summarily” rejected the argument. So confident was the Department of Energy that the rule failed at the threshold that the Department did not even bother to defend the rule on the merits in briefing (for which it earned the Court’s rebuke). The Department nevertheless insisted that it would be able to provide “a full and sound explanation” for the Rule on remand, which leads to the third interesting feature of the decision: Despite the Department’s failure to reveal its justifications for the rule, the panel applied Allied-Signal to remand the rule without vacating it. Since the D.C. Circuit adopted the controversial but widely used “remand without vacatur” remedy thirty years ago, the remedy has been subject to a variety of legal and practical criticisms, among these, that keeping the rule in place deprives the agency of any “incentive to fix the deficient rule.” To avoid this problem , the panel ordered that the rule would be vacated if the Department fails to “take appropriate remedial action within 90 days.” In doing so, it followed the advice of our fellow D.C. Circuit Review—Reviewed author Judge Griffith, who in 2008 encouraged his colleagues to consider alternatives to “open-ended remand without vacatur.”

In City of Miami v. FERC, the Court also remanded for the agency to show its work. The City of Miami filed a complaint with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission charging that the Grand River Dam Authority is violating its license by failing to acquire title to or an easement on land in the City of Miami that routinely floods due to the Authority’s operation of the Pensacola Dam. (The Pensacola Dam spans the Grand River near the town of Disney, but you may be surprised to learn that this case has nothing to do with Florida—all of these locations are in the Great State of Oklahoma, where Miami is pronounced “My-am-uh.”) FERC rejected the complaint on grounds Judge Silberman (joined by Judges Henderson and Pillard) found “surprisingly unpersuasive.”

The Court flatly rejected one of FERC’s grounds for denying Miami’s complaint: that FERC could address the flooding problem in an upcoming relicensing proceeding. This rationale “runs afoul of a basic principle of administrative law: an agency faced with a claim that a party is violating the law (here an existing license) cannot resolve the controversy by promising to consider the issue in a prospective legal framework.” The Court then remanded for the agency to address the four other defects in its order. Perhaps the most interesting is FERC’s failure to explain the impact of the Pensacola Act, which Congress passed in the midst of the dam controversy in an apparent effort to resolve the controversy. The statute cryptically provides that “[t]he licensing jurisdiction of the Commission for the project shall not extend to any land or water outside the project boundary.” Because the flooded land in Miami lies outside the project boundary, FERC reasoned that the Act deprived it of authority to require the Grand River Dam Authority to acquire the land. FERC also argued that the Act deprived the Court of Article III jurisdiction because it made Miami’s injury irremediable. The Court rejected FERC’s effort to turn “a merits issue” into a jurisdictional one, but it found the meaning of the Act ambiguous and left it to FERC to construe the provision in the first instance.

The agencies were more successful in defending against the other petitions for review. Duke Energy Progress LLC v. FERC arose from dispute between Duke Energy and the North Carolina Eastern Municipal Power Agency. Under an energy purchase contract, Duke charges the Agency in part based on the Agency’s pro rata share of the demand on Duke’s system in a one-hour “snapshot” of system usage taken during the peak hour. The Agency charges batteries during off-peak hours and then uses the batteries to supply energy to its customers during peak hours, thereby reducing its pro rata share of the demand in the snapshots. The Agency sought a ruling by FERC that its tactic is a permissible form of “Demand-Side Management” or “Demand Response”—both of which the parties’ contract permits. FERC agreed with the Agency, and Duke petitioned for review.

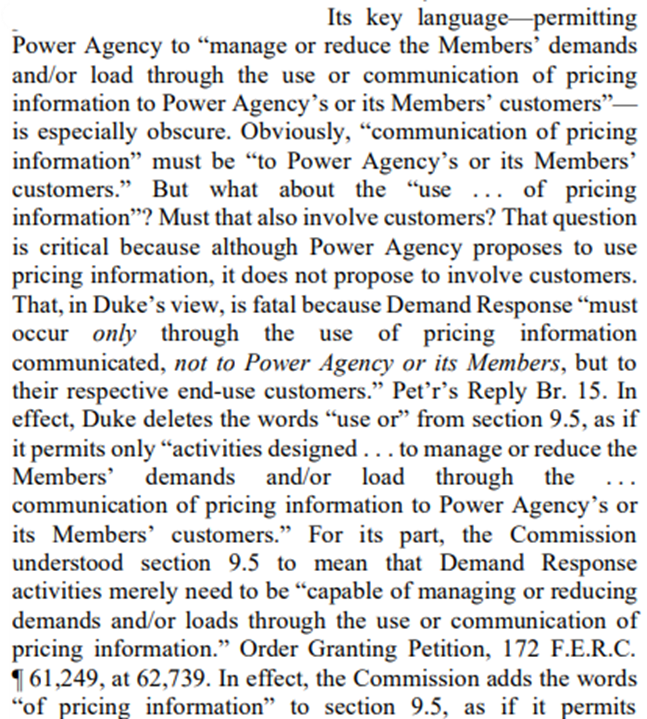

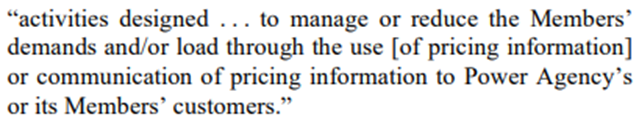

The Court focused its analysis on “Demand Response,” which the contract defines as “activities designed . . . to manage or reduce the [Agency’s members’] demands and/or load through the use or communication of pricing information to [the Agency’s or its members’] customers.” Duke argued that “Demand Response” covers only reductions in demand that the Agency achieves through communicating pricing information to customers. The Agency relied on pricing data to predict peak-usage hours and deploy its batteries accordingly, but it did not communicate that data to customers. The D.C. Circuit applies Chevron deference to FERC’s interpretation of ambiguous energy contracts, and Judge Tatel (joined by Judges Henderson and Pillard) found the “Demand Response” provision to be a “model of ambiguity.” Judge Tatel cogently explains why:

The Court therefore deferred to FERC’s interpretation and denied Duke’s petition. In doing so, it also rejected Duke’s argument that the interpretation makes the contract confiscatory. If the Agency manages to reduce its usage to a point that Duke could not recover its costs, then Duke remains free to petition the commission to reform the parties’ contract.

In Intercontinental Exchange, Inc. v. SEC, the Court resolved a petition for review of an SEC order approving fees for wireless connection services provided by affiliates of securities exchanges. I refer readers to Judge Ginsburg’s opinion (joined by Judges Katsas and Walker) for an explanation of the function and importance of these services, complete with Judge Ginsburg’s favored graphical depictions.

The exchanges are self-regulatory organizations that set their own rules, subject to SEC approval. Among other things, the SEC has jurisdiction over rules governing “facilities of an exchange.” The exchanges submitted the proposed fees to the SEC under protest, arguing that the wireless connection services are not “facilities of an exchange.” The Court rejected the exchanges’ interpretation of that term, this time without invoking Chevron. Even though the wireless connection services do not link directly to exchange machinery that matches buy and sell orders, they are facilities of an exchange.

Although the SEC approved the proposed rates, the exchanges also charged it with acting arbitrarily and capriciously. For example, the exchanges argued that the SEC failed to consider how subjecting their wireless connection services to SEC jurisdiction would disadvantage them relative to competing connection services. The Court ruled that “this argument conflates two distinct questions: (1) whether an organization is one the Congress decided ought to be subjected to the rule-approval process, and (2) whether the SEC ought to approve a particular rule proposed by an SRO.” The requirement that the SEC consider the impact of a rule on efficiency and competition applies to the SEC’s rule-approval determination, not to the determination of the SEC’s jurisdiction.

Turning from the petitions to the appeal, the Court’s decision in RICU LLC v. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services concerns the scope of the Medicare Act’s jurisdictional “channeling” procedure. The channeling procedure requires individuals to present a concrete claim for payment of rendered services to the Department of Health and Human Services before seeking judicial review of Department action. The claimant in this case, RICU, contracts with U.S.-licensed physicians residing abroad to provide critical care telehealth services in the United States. Medicare does not typically reimburse expenses incurred for critical care telehealth services, but the Department temporarily authorized reimbursement for the duration of the coronavirus public health emergency. RICU sought clarification of whether its services would be reimbursable. The Department determined that the services would not be reimbursable because RICU’s contract physicians are located outside of the United States, and the Medicare Act independently bars foreign payments. RICU challenged that determination under the APA, and the district court dismissed on the ground that RICU had not presented a concrete claim for payment, as required by the channeling procedure.

The Court affirmed. Judge Rogers (joined by Chief Judge Srinivasan and Judge Jackson) first rejected RICU’s argument that its appeal to the Department for a clarification followed the channeling procedure because the appeal did not take the form of a concrete claim for payment of services already rendered. The Court then rejected RICU’s argument that it was entitled sidestep the channeling procedure in order to obtain judicial review. The Supreme Court has held that a party need not follow the channeling procedure when the consequence of enforcing the procedure would altogether deprive the party of judicial review. The D.C. Circuit has only once applied this exception, however, and it refused to do so here. It concluded that, although RICU has no opportunity to submit a concrete claim for payment because it is not a Medicare enrolled provider, its client hospitals have a sufficient incentive to pursue claims for payment on RICU’s behalf.

One could perhaps analogize the latter holding to third-party standing. Not that the client hospitals would rely on third-party standing to seek reimbursement for RICU’s services; they would have standing in their own right. But here we have a Supreme Court ruling that some form of judicial review must be available for a party injured by a Medicare determination (as a matter of statutory construction), and the D.C. Circuit has held that making review available to a third party whose interests align with the aggrieved party fulfills that requirement. I wonder if there is another context in which third-party claims satisfy a right to judicial review. One hopes for RICU’s sake that its client hospitals will cooperate.

D.C. Circuit Review – Reviewed is designed to help you keep track of the nation’s “second most important court” in just five minutes a week.