Dissenting Commissioners, by Todd Phillips

Administrative law is generally conditioned on agency action. Notice and comment rulemaking mandates “the agency shall give interested persons an opportunity to participate in the rule making.” 5 U.S.C. § 553(c). Chevron deference contemplates judicial consideration of “an agency’s construction of the statute which it administers,” and Auer deference requires judges to consider “the agency’s construction of its own regulation.” APA adjudications may be held before “the agency, one or more members of the body which comprises the agency, or one or more administrative law judges,” and it is the “final agency action” that litigants may appeal in court.

Administrative law rarely delves into the question of what is an agency. For the most part, “the agency” is a stand-in for the Secretary or Administrator (in the case of a single-director agency), the majority of the commission (in the case of multi-member agencies), or an individual with delegated authority. And for the most part this theory works: rules are promulgated, cases are adjudicated, and the public understands their legal rights and responsibilities.

However, sometimes in multi-member agencies, the presumption that the agency is all commissioners and an agency’s action is what a majority of commissioners vote for creates a strange result: a majority may silence dissenting commissioners. Two recent examples demonstrate this problem in action.

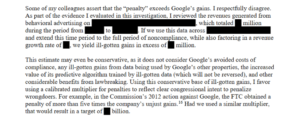

In early September, the Federal Trade Commission approved a settlement with Google (see In the Matter of Google LLC and YouTube, LLC) on a 3-2 vote, with the two Democratic Commissioners dissenting. This seemed to be a pretty standard settlement, where Google neither admitted nor denied wrongdoing, and all five Commissioners released statements on the settlement. However, what was not standard was that Commissioner Rohit Chopra’s dissenting statement was redacted:

There does not appear to be an explanation anywhere offering an explanation for the redactions, leading one publication to state:

Either Google was somehow able to intimidate the FTC into redacting a commissioner’s figures about how much money the company made from ads targeted at children over the time period at issue in the case (even that time period is redacted and non-public), or the three Googlefied commissioners decided they didn’t want to offend a mega-company they’re supposedly charged with regulating.

The second example concerns the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. In August, the CFTC settled a civil action with Kraft Foods and Mondelēz Global. The Consent Order between the defendants and the Commission stated, “[n]either party shall make any public statement about this case other than to refer to the terms of this settlement agreement or public documents filed in this case.” Upon approving the order, the CFTC’s public affairs office issued a press release, the five commissioners jointly issued a “Statement of the Commission,” and two commissioners issued a concurring statement.

According to the defendants, statements made in all three documents violated the Consent Order, and the defendants filed a motion for contempt in district court. Among other arguments, the defendants believed that the Commission violated the Order because of statements of the two commissioners. After some back and forth, the Commission petitioned the Seventh Circuit for a writ of mandamus to stay the district court’s proceedings. This October, writing for a three judge panel, Judge Easterbrook ruled that “there is neither need nor justification for testimony by the Chairman, any Commissioners, or any members of the agency’s staff.”

Judge Easterbrook stated that “every member of the Commission has a right to publish an explanation of his or her vote,” but only because of a statute specific to the CFTC. The Commodity Exchange Act states:

Whenever the Commission issues for official publication any opinion, release, rule, order, interpretation, or other determina-tion on a matter, the Commission shall provide that any dissent-ing, concurring, or separate opinion by any Commissioner on the matter be published in full along with the Commission opinion, release, rule, order, interpretation, or determination. 7 U.S.C. §2(a)(10)(C).

Judge Easterbrook continued, writing, “This is a right that the Commission cannot negate. It could not vote, three to two, to block the two from publishing their views,” and that a consent decree cannot override the statute.

This is worrisome. The logic behind Judge Easterbrook’s opinion is that, without this statute, a majority of the Commission could limit the other commissioners’ statements. I haven’t scoured the U.S. Code, but I would venture a guess that not every multi-member agency has such a provision in their organic statute. It is possible that such a limit was placed on FTC Commissioner Chopra’s statement by a majority of his colleagues.

In and of itself, that a majority may silence a minority is concerning; it fundamentally goes against the free speech principles the country prides itself on. However, I want to raise one other issue for consideration. Usual Notice and Comment readers are likely well-versed in the logic of then-Judge Kavanaugh’s panel decision in PHH Corp v. CFPB and subsequent dissent to the en banc decision, which also appears to be the basis for this Supreme Court term’s Seila Law v. CFPB. One part of his constitutional theory is that multi-member agencies have checks and balances that an agency with a single director doesn’t. In one paragraph, then-Judge Kavanaugh writes,

[A]s compared to a single-Director independent agency, a multi-member independent agency (particularly when bipartisan) supplies a built-in monitoring system for interests on both sides because that type of body is more likely to produce a dissent if the agency goes too far in one direction. A dissent, in turn, can serve as a “fire alarm” that alerts Congress and the public at large that the agency’s decision might merit closer scrutiny. [Internal citations and quotation marks omitted.]

This is only a small part of then-Judge Kavanaugh’s theory, but it raises an important issue: if multi-member independent agencies are constitutional because dissenters can express their concerns with the majority’s actions, what happens if dissenters can’t?

Administrative law currently does not have a good way of dealing with commission minorities and ensuring they are able to articulate their concerns with the actions of the majority. Perhaps it should.

Todd Phillips is a government lawyer in Washington, DC. This post expresses the author’s personal views alone.