Distributional Weights Should Be Dropped from the Draft Circular A-4, by Mary Sullivan

*This post is part of a symposium on Modernizing Regulatory Review. For other posts in the series, click here.

Cost-benefit analysis is a critical part of rulemaking because it helps the government efficiently allocate its resources. Sometimes efficiency must be sacrificed to ensure that regulations are equitable. Policymakers must balance efficiency and equity in a judicious way, which requires knowledge of the true costs and benefits from regulations and how the regulations affect different groups.

The draft Circular A-4 addresses equity by encouraging agencies to apply distributional weights to the costs and benefits of different groups based on income, race, sex, disability, and so on. The motivation for using these weights is to “account for the diminishing marginal utility of goods when aggregating those benefits and costs.”

There are several problems with the weights. First, weighting costs and benefits could result in large losses in efficiency. When benefits and costs are weighted, they deviate from the actual benefits and costs experienced by individuals. The weights could cause agencies to adopt regulations for which the costs exceed the benefits and forgo regulations that have positive net benefits. This is the problem Arnold Harberger was referring to when he said that “the implications for policy of a thorough and consistent use of distributional weights turn out to be quite disturbing.”

Second, the weights have no basis in theory. Use of the weights assumes that redistributing income increases total welfare. However, as economist Deirdre McCloskey pointed out, asserting that a poor person obtains more utility from an additional dollar of income than does a rich person “is, regrettably, meaningless.” Therefore, there is no reason to believe that a distributional analysis based on the weights would result in more equitable regulations.

Third, use of the weights would reduce transparency. Presenting the weighted estimates alongside the traditionally-weighted estimates could be confusing and make it more difficult for the public to know how the decisions were being made.

Finally, the weights imply a fact-based precision that makes policymakers think that they are making a scientific decision, when in fact the value judgment is buried in the numbers. The adoption of the weights over time would replace judgement with a formula incapable of incorporating the nuances of regulations into distributional analysis.

Using Distributional Weights

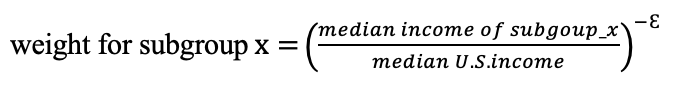

The weights of a particular subgroup are calculated by first dividing the median income of that subgroup by the U.S. median income and second, raising this ratio to the power of the elasticity of marginal utility times negative one:

where Ɛ = the elasticity of marginal income.

The weighted analysis would record $100 in benefits as $264 for someone earning half the median income and $696 for someone earning a quarter of the median income. For someone earning 1.5 times the median income, $100 in benefits would be recorded as $57, and for someone earning twice the median income, $38. This means that a benefit of a given amount would be recorded as 18.3 times higher for someone earning one quarter of the median income than for someone earning twice the median income. The weights would have the same effect on the costs of various groups.

How the Weights Purportedly Address Equity

Although the weights do not actually redistribute income, the logic used to justify them relies on the belief that redistributing income increases total welfare. In explaining how distributional weights work, Acland and Greenberg (2022) say, “For any given income group, the welfare-weighted WTP [willingness to pay] represents the WTP they would express, for the welfare impact they experience, if they had the median income.” Costs are weighted, the argument goes, because a dollar is more important to a low-income person than to a high-income person.

This interpretation of the weights is based on the belief that redistributing income would cause a poor person’s utility to increase by more than a rich person’s utility would fall. Economic theory does not provide a basis for this belief. The utility function serves only to rank an individual’s preferences for different quantities or bundles of goods, not to compare the utility of different people.

A second flaw in this interpretation of the weights is that the income elasticity of demand for the benefits of a regulation is not the same across individuals. Income elasticity of demand indicates how sensitive an individual’s demand for a particular good is to changes in income. Implicit in the use of the weights is the assumption that a change in income would cause the willingness to pay for regulatory benefits to change in proportion to the weights. However, when income increases, people spend the income on goods and services that maximize their utility. Because people have different elasticities of income for different things, it is incorrect to assume that their willingness to pay for a regulation would increase in proportion to the weight for their group. A poor person may prefer to use extra income to buy new shoes or better food for their kids, not to reduce small amounts of air pollution.

Without a valid foundation, there is no justification for arguing that the weights can be used to determine how much society should value the benefits and costs of a regulation for different groups.

Value Judgment Versus Formula

A value judgment is required to develop regulations that achieve the right balance between equity and efficiency. There are nuances in policy decisions that make formulas less useful than judgment in achieving this balance. For example, when some benefits and costs cannot be monetized with precision, judgment must be used to decide how they should be counted in the policy decision. This formulaic approach would simply multiply the weights by all the benefits and costs except the value of mortality risk reductions, regardless of how precisely they were estimated, and misrepresent to policymakers and the public the level of confidence in the estimates.

The draft circular gives agencies the option of using the weights, but does not require it. Initially they may be reluctant to use the weights due to lack of data and lack of familiarity with the process. However, over time, with improvements in data and more experience using the weights, the weights could gradually replace judgement in distributional analysis, with agencies routinely using them while believing them to provide a valid measure of how society values the costs and benefits of regulations.

Conclusion

The weights proposed in the draft circular A-4 are based on misguided economic assumptions and would introduce large inefficiencies into cost-benefit analysis. They would reduce transparency and could gradually replace the use of judgment in policy decisions.

For these reasons, the weights should be dropped from the draft circular A-4.

Mary Sullivan is a visiting scholar at the George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center and an adjunct professor in the Trachtenberg School of Public Policy and Public Administration.