Does Chevron Deference Violate Article III? Article III Would Like a Word, by Kent Barnett

I’ve engaged in some deviant behavior. I did something you aren’t supposed to do—with someone else or alone. At least if you’re an academic.

I’ve written a purely doctrinal article. And I’m not sorry.

My latest article, invited for the George Washington Law Review’s Annual Review of Administrative Law, considers—well, the title says it all—How Chevron Deference Fits into Article III. If you’re looking for deep theory and normative takeaways divorced from doctrine, please go elsewhere. Or if you want to consider Chevron’s constitutional propriety on freshly quarried slate, you probably won’t care what I have to say.But if you want to consider Chevron deference’s constitutionality under current doctrine and care about stare decisis, continue on.

U.S. Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch, along with Professor Philip Hamburger, assert that Chevron deference—under which courts defer to reasonable agency statutory interpretations—violates Article III. Chevron does so because, they argue, it either permits agencies, not courts, “to say what the law is” or requires judges to forgo independent judgment by favoring the government’s position. If they are correct, Congress could not require courts to accept reasonable agency statutory interpretations under any circumstances.

My article does what these critics perhaps surprisingly do not do—situates challenges to Chevron within the broad landscape of the Court’s current Article III jurisprudence.

A thorough study of Article III jurisprudence hobbles these blunderbuss Article III challenges to Chevron but leaves room for narrow attacks.

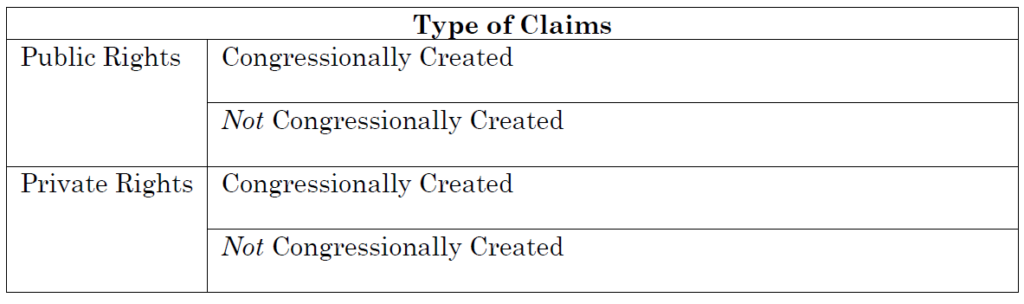

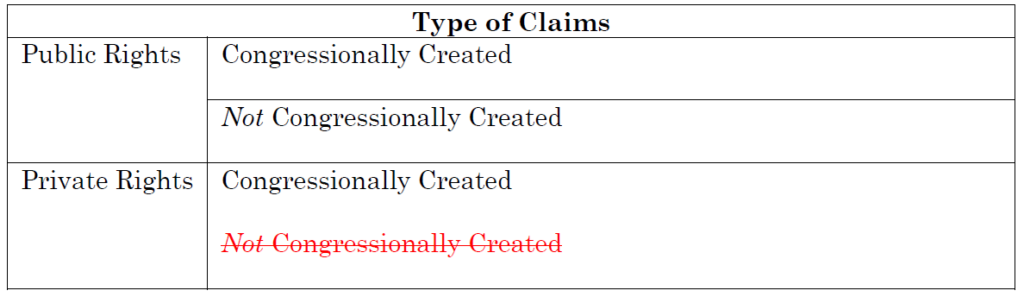

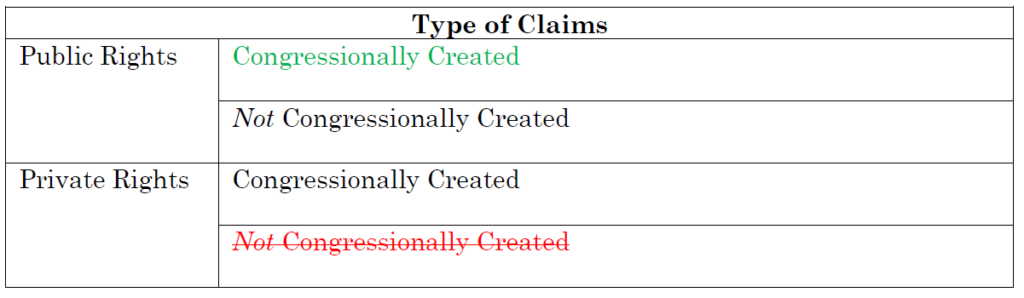

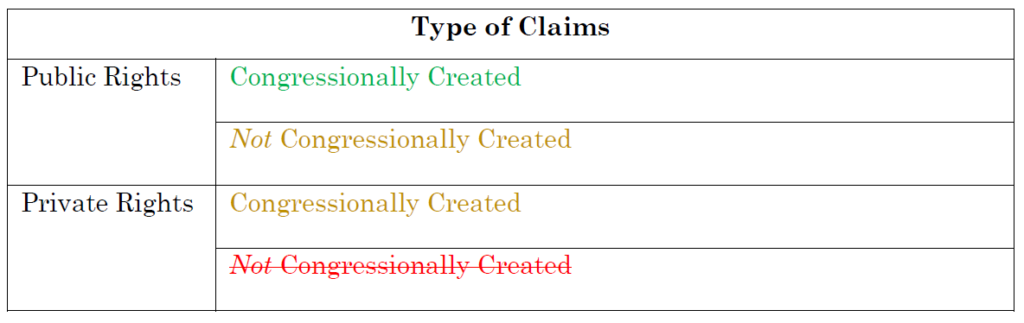

Derived from the plurality in Northern Pipeline v. Marathon Pipe Line Co., a four-quadrant matrix informs Congress’s power to limit Article III adjudication or review. The quadrants concern public and private rights, each subdivided (mostly) by claims that Congress created and did not create:

Public rights are those in which the government is a party to an action or which are an integral part of a complicated regulatory scheme. Congress has more room within Article III to limit judicial review for both public rights and private rights that it creates and the most room with public rights that it creates.

With that extremely brief background in mind, let us approach each quadrant. (Article III doctrine is complex and nuanced. What follows is necessarily generalized from the discussion in the article.)

First, Chevron does not apply to what is the most contentious and perhaps most unsettled quadrant—private rights that Congress did not create—because Chevron only applies to federal agency statutory interpretation of (federal) statutes that the agency administers. Thus, we can put one of the four quadrants aside.

Second, Chevron most often applies in the quadrant in which Congress almost certainly can limit de novo judicial review—public rights that Congress creates, such as those that arise in licensing and benefits programs. The Administrative Procedure Act permits Congress to preclude judicial review altogether (including as to legal questions), and the Court has never appeared to question this provision’s applicability to statutory questions. Moreover, the key distinction between private and public rights is that Congress can remove public rights (at least those that it creates) from judicial consideration completely, meaning that agency statutory interpretation prevails without any judicial approbation. If Congress can remove agency statutory interpretation concerning public rights from judicial review altogether, it is difficult to see how Congress’s lesser power to merely limit judicial review to reasonableness review of agency statutory interpretation would offend Article III.

Before going further, our limited analysis reveals something important: the battle over Chevron should not be a global one. Because it is almost certainly permissible where it most often applies (to public rights that Congress creates), it should instead be fought on limited terrain.

Two quadrants remain where Chevron sometimes applies—public rights that Congress did not create (including, for traditional reasons, criminal law) and congressionally created private rights. The former category would include federal criminal law and constitutional claims; the latter category would include statutory claims, such as reparation claims in commodities. Chevron’s application in these latter two quadrants should counsel caution (hence the yellow shading on the chart below) because the Court has more jealously guarded Article III adjudication there than with public rights that Congress created.

Yet even within these two quadrants, other strands of Article III doctrine suggest that Congress has some space to limit courts’ “independent judgment.”

First, similar to Congress’s ability to preclude judicial review of public rights that it creates, Congress can limit the lower federal courts’ jurisdiction over these claims altogether. It also has extremely broad, although perhaps not unlimited, power to limit the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction. Moreover, nothing in the APA’s preclusion provisions limits their reach to public rights.

Second, even if Congress bestows jurisdiction over claims, Congress can interfere with judicial decision making. For example, it can do so by amending law or setting rules of evidence and procedure that are relevant to pending litigation.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, it can limit plenary judicial review of legal interpretation. For instance, federal judicial review of state-court habeas matters is, in essence, a form of minimal reasonableness review. Indeed, for the en banc court, Seventh Circuit Judge Easterbrook rejected arguments against limited federal habeas review by noting that if limited review in habeas were unconstitutional, Chevron, too, would be unconstitutional. No court, as far as I am aware, however, has held that limited habeas review violates Article III. Or as another example, courts must review for only manifest legal errors when deciding whether to enforce arbitration awards. In Thomas v. Union Carbide, the Court rejected an Article III challenge to a statutory scheme that required private parties to head to arbitration if they had certain disputes concerning pesticide registrations. Notably, the Court was not troubled that courts could review the arbitrator’s award for only “fraud, misconduct, or misrepresentation” or that the parties had no meaningful choice in dispute-resolution venue. In these and other instances, the courts decide whether to grant or deny a remedy—whether habeas relief or money damages—without plenary review.

For the two quadrants where Chevron’s presence is suspect, I do not decide whether Article III permits or forbids Chevron. Instead, my object is to demonstrate that Chevron should potentially cause alarm in only limited areas. I leave courts and parties to decide Chevron’s fate when it, with comparative rarity, appears in these two quadrants by considering, for example, other strands of Article III that I discuss here, originalist arguments, or theoretical justifications.

Chevron, in other words, is not an abomination to Article III. At most, it may be just a bit like a law professor writing about doctrine—a little deviant, too.

Kent Barnett is the J. Alton Hosch Associate Professor of the University of Georgia School of Law.