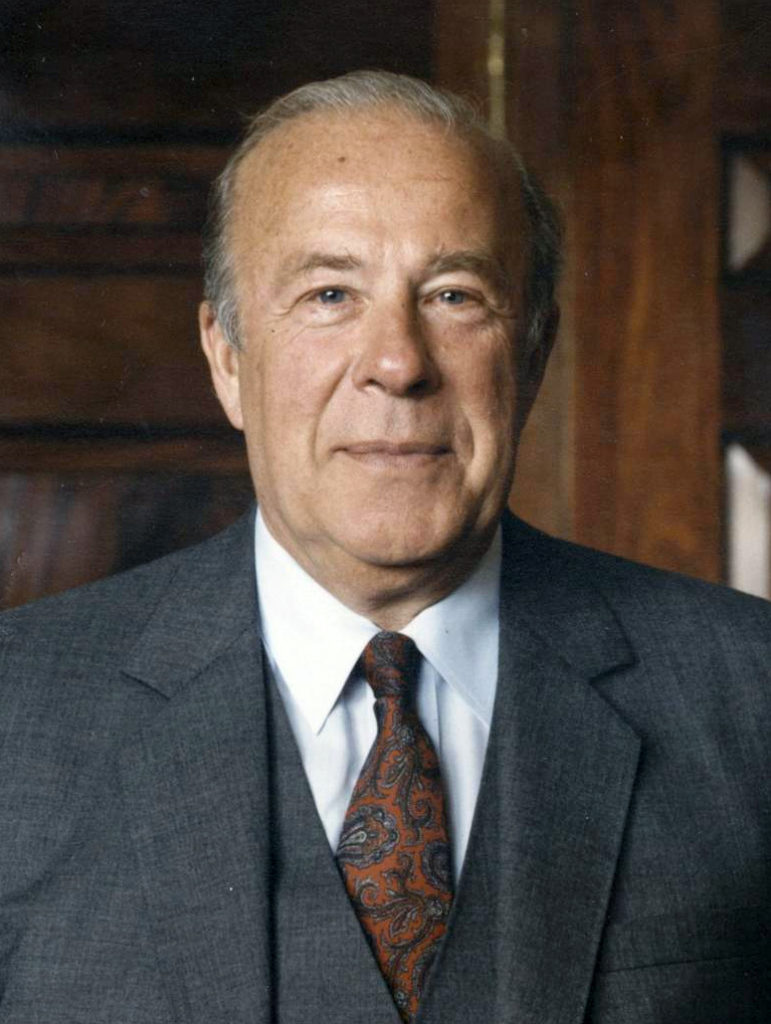

George Shultz’s statesmanship began with good government at home

When George Shultz passed away last week, America lost one of the 20th Century’s greatest statesmen. His death, months after his 100th birthday, spurred an outpouring of obituaries and remembrances, a fitting tribute to an extraordinary man. He had an unparalleled career of public service, in four cabinet positions — Director of the Office of Management and Budget, and Secretary of Labor, the Treasury, and State.

But reading those articles, which focused overwhelmingly (and understandably) on Shultz’s work as Secretary of State, I was particularly struck by an insight from my colleague Nicholas Eberstadt, contrasting Shultz with his famous predecessor, Henry Kissinger:

For all its great learning and extraordinary skill, Kissinger’s statecraft was limited by a huge blind spot, for he was an economic naif. Shultz, the econ professor from MIT and dean of the Chicago business school, most assuredly was not.

Shultz understood the extraordinary strategic advantages the American free market system possessed over Soviet-style economies, and US strategy on his watch capitalized on them: from “star wars” and the revolution in military affairs to promoting the launch of the information era.

This is a crucial insight. Shultz himself often highlighted the fundamental relationship between America’s capacity to do good abroad, and America’s capacity for innovation and economic vibrancy at home.

When Shultz’s diplomatic memoir, Turmoil and Triumph, was published in 1993, he emphasized the point in an interview with C-Span’s Brian Lamb, who asked him how his education in economics helped him to recognize why the United States could win the Cold War:

SHULTZ: … And I had said in speeches around Stanford, before I was secretary of state, that their system just couldn’t measure up to ours from an economic standpoint and, of course, morally it was a bankrupt system, as Krushchev brought out.

LAMB: Why didn’t it work?

SHULTZ: It didn’t give people the freedom and creativity that I think they instinctively want. And it was repressive, so it was resented, even though there was control. And I think that in this day and age, a modern economy, big economy, just cannot be managed from the top, and they realize that.

Shultz returned to these themes again and again — in interviews for Daniel Yergin’s Commanding Heights; in one of his last books, co-authored with the economist John Taylor.

Secretary Shultz might not be a significant figure in the minds of administrative law specialists. But in fact he had a significant impact on our own field, a decade before he became Secretary of State. Because in his earlier government service as Secretary of Labor and OMB Director, he focused squarely on the effects that regulations have on economic growth and the innovative spirit.

Most importantly, as OMB Director, George Shultz enacted the original “Quality of Life Review” framework that would become the precursor for today’s OIRA framework.

Shultz’s memoranda, archived at Jim Tozzi’s Center for Regulatory Effectiveness, are well worth re-reading in our own time. In that earlier era fifty years ago, when American politics was energized by the pursuit of regulatory benefits, especially in protecting the environment, OMB Director Shultz and his colleagues understood that the costs of regulation would also be significant. So they take care to frame up a process to ensure that energetic regulators would not forget to look at both sides of the policymaking ledger. Jim Tozzi recounted this foundational moment ten years ago, for OIRA’s fortieth anniversary; so did Andrew Rudalevige in his account of OIRA’s pre-history.

A few years after his time at OMB (and then Treasury Secretary), Shultz’s initial work with Ronald Reagan would focus not on foreign policy but domestic policy. In 1980 he chaired Reagan’s Coordinating Committee on Economic Policy, and days after Reagan’s electoral victory delivered a set of task-force reports that would help to chart the course for the Reagan Administration’s agenda. And in his cover memo, Shultz highlighted the need for the Reagan Administration to focus more comprehensively and precisely on the costs of regulation, and the need for the President to create an office in the White House with specific responsibility for overseeing this administration-wide, inter-agency process. Those regulatory-reform proposals, summarized publicly by Murray Weidenbaum in the November-December 1980 issue of Regulation, look familiar today: “establish a new White House office, either placing it within OMB or giving it separate status,” to “assume the regulation monitoring, review, and information dispensing functions,” focusing especially on regulatory costs and benefits.

A little more than a year later, President Reagan would appoint Shultz to be his Secretary of State, changing the course of Shultz’s career—and, it turned out, the course of world history. Yet Shultz’s pre-State attention to the importance of economic innovation and regulatory burdens is well worth considering now—not simply because of the sad news of his passing, but also for its relevance to our present moment.

Our own field of administrative law and public administration is not self-contained; it is not an end in itself, but a means to much larger ends. Yet even those who recognize that fact, as virtually everyone does, still risk ignoring how immense the stakes truly are.

After years of American decline from its position of international leadership, our nation needs to focus not just on repairing international institutions and domestic institutions, but also on restoring and promoting America’s own capacity of economic growth and innovation. Those domestic capacities are necessary prerequisites for both soft power and hard power on the global stage. And those capacities depend significantly on building and reforming institutions of governance at home, to promote administrative stability while also reducing regulatory burdens wherever possible, precisely so that American innovation and ingenuity can flourish. Our society, our government, and our diplomacy depend on it. Mr. Shultz understood this connection throughout his career.

And so, even late in his career, when Mr. Shultz focused his energies on the problem of global climate change, he was capable of focusing not just on the need for significant U.S. government action (both at home and abroad), but also on the need to rely as much as possible on market mechanisms: namely, the enactment of a well-designed carbon tax that would cause private actors to internalize the costs imposed by carbon emissions, which otherwise are borne by humanity at large; and then coupling that new tax with a corresponding reduction of government regulations.

Such an approach, he wrote last year, “could actually shrink the size of government by rendering less efficient regulations unnecessary. This would provide businesses the regulatory certainty they need to make long-term investments in clean energy, further turbocharging the innovation engine.”

Mr. Shultz studied and advocated for these reforms throughout the last decades of his life, at the Stanford’s Hoover Institution, where he and Ambassador Tom Stephenson co-directed task force that gathered experts from across partisan, ideological, and disciplinary lines for serious discussions of the facts of climate change and the possible pathways for reform. In my own time as a Hoover research fellow, I had the honor and pleasure of participating in some of the task force’s work, where I saw firsthand not only how active and focused Mr. Shultz was, even in his late 90s; but also how his recognition of American markets as an indispensable foundation for American government.

Countless times, Mr. Shultz’s admirers have recounted his story about the globe in his office at the State Department, and how he would ask ambassadors heading abroad to spin the globe and point to their country. “Never forget,” he said, “you’re over there in that country, but your country is the United States. You’re there to represent us. Take care of our interests and never forget it, and you’re representing the best country in the world.”

George Shultz knew his country—not just which it was, but what it was. His country, and the world, benefitted immensely from that.

Adam J. White is a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and director of George Mason University’s C. Boyden Gray Center for the Study of the Administrative State.