Have the SEC’s Delay Tactics Made Its Petition for Rulemaking Process Vulnerable to Challenge? A Look at In re Coinbase Inc. and SEC’s Nullification of 5 U.S.C. § 553(e) by Inaction, by Kara McKenna Rollins

Last week, Coinbase launched its first counteroffensive against the Securities Exchange Commission’s (“SEC”) aggressive enforcement posturing in the cryptoeconomy. The cryptocurrency trading platform filed a petition for writ of mandamus asking the Third Circuit to make the SEC act on its petition for rulemaking. The filing raises important questions about administrative power in several respects including agency nullification of the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”).

First, petitions for mandamus requesting an agency to act on rulemaking petitions are rare, possibly nonexistent until now.[1] Second, Coinbase, having recently received a “Wells notice,” is under threat of enforcement by the SEC. Third, the petition does not push a particular outcome beyond getting the Commission to take an action, any action, that is final and appealable under the APA section 704. Fourth, it articulates a theory of “unreasonably delayed” that the courts have not addressed when reviewing agency inaction regarding rulemaking petitions, i.e., that the unreasonable delay inquiry is relative.

But Coinbase’s petition also misses a critical issue—that SEC’s lassitude is the rule not the exception.

While the APA section 553(e) provides that agencies “shall give an interested person the right to petition for the issuance, amendment, or repeal of a rule” it is silent regarding the particulars. The SEC’s procedures relating to rulemaking petitions are minimal. To SEC’s credit, it is one of the few agencies that makes the petitions for rulemaking it receives, and comments thereto, public and searchable. But transparency about receiving rulemaking petitions and substantively responding to the petitions are different things altogether.

In 2014, the Administrative Conference of the United States issued a comprehensive review and report on petitions for rulemaking (“ACUS Report”), providing valuable information about how agencies receive, process, and resolve rulemaking petitions. At that time, SEC reported receiving 10 petitions, but there was no other historical data available.

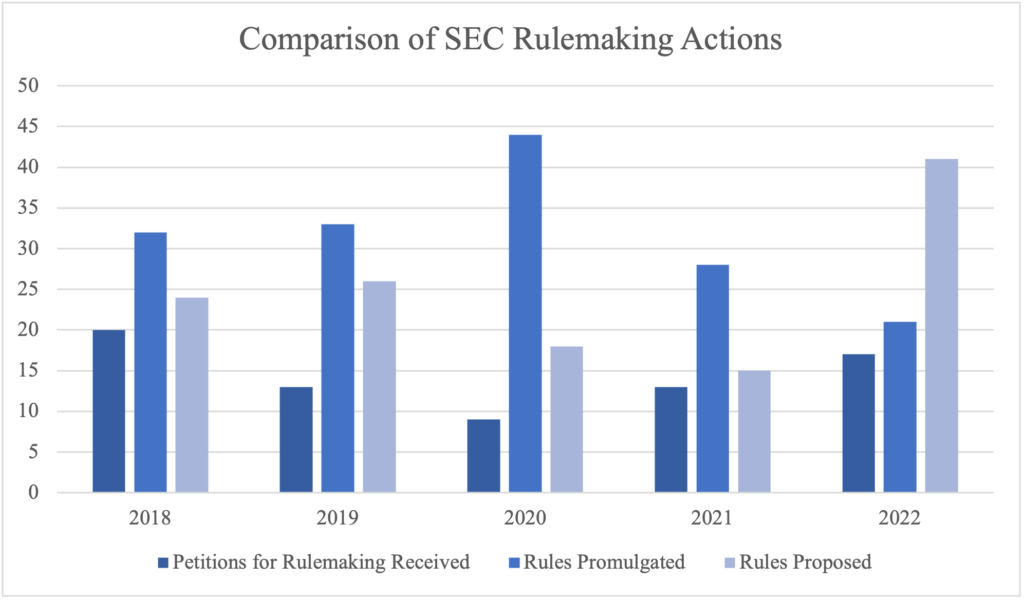

Since the ACUS report was issued, SEC has seen an uptick in the number of petitions it receives.[2] Between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2022 the SEC received seventy-two rulemaking petitions. During that period, SEC received an average of fourteen petitions per year, with a highwater mark of twenty petitions in 2018. In comparison, the SEC promulgated about thirty-one rules per year, with forty-four issued in 2020.[3] The SEC proposed an average of twenty-four rules during that period, proposing forty-one in 2022.[4] The chart below summarizes this data:

So far this year, SEC has received five petitions for rulemaking, promulgated eight rules, and proposed eight rules.[5] SEC’s regulatory agenda shows few signals that the Commission is slowing down its regulatory machinery through the rest of 2023.

As the ACUS Report suggested, it may be generally “difficult to gauge how often agencies ‘grant’ or ‘deny’ petitions” because those terms are not defined across agencies, it is not difficult to determine when rulemaking petitions have languished. And as Coinbase’s mandamus action suggests, a more important metric may be whether the agency responds in such a way that its action may be deemed final and appealable under the APA. Indeed, the very purpose of section 553(e) is to permit an “interested person” to submit a “petition for the issuance, amendment, or repeal of a rule.” And, as Coinbase highlights, that purpose is frustrated by agency inaction that works as a “pocket veto.”

So, what happens to petitions for rulemaking after they are submitted to the SEC? Not much it seems. As one petitioner has described it in the ACUS Report, after a rulemaking petition’s initial receipt by the SEC, the Commission’s process was effectively a “black hole.” Indeed, this author has had similar experiences with the SEC’s petition for rulemaking process.[6] Just last year, Judge Jones, joined by Judge Duncan in a concurring opinion, chided the SEC for its years-long inaction on a rulemaking petition in light of the perception that the SEC maintains an aggressive rulemaking and enforcement agenda.[7]

The numbers support these concerns. Of the seventy-seven petitions submitted since January 1, 2018, the SEC only substantively responded[8] to five (6.5%).[9] And of those, only one (1.2%) led to promulgation of a final rule. Even if the 2023 rulemaking petitions are excluded from these counts to allow time for the Commission to respond, the needle does not move much as the SEC still only substantively responded to five of seventy-two (6.9%) petitions.

Of the seventy-seven rulemaking petitions SEC has received since January 2018, less than a third had comments. And of those twenty-five, the SEC only substantively responded to four (16%). Curiously, in one proposed rule the Commission remarked about the lack of comments submitted regarding a pending rulemaking petition, which the Commission never responded to. This would make some sense if whether a petition received comments indicated that the SEC would respond to a petition for rulemaking, but the data does not appear to support such a conclusion. To be sure, of the small percentage of rulemakings the SEC responded to, the majority had received comments, but those only represent 5.2% (four of seventy-seven) of all petitions submitted since January 1, 2018. By contrast, during that same period, just 1.3% (one of seventy-seven) of rulemaking petitions submitted that received no comments were substantively responded to.

If receiving comments is not a positive indicator for generating a substantive response from the SEC, what is? Nominally, the answer may be that the content of the petition should have broad support and be a common-sense and necessary change. For example, the only rulemaking petition (SEC File No. 4-760) reviewed that was subsequently promulgated as a final rule sought to change wet signature requirements during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. The final rule noted that the rule change furthered in the petition was supported by “nearly 100 public companies[.]” It also noted that technology, by means of electronic signature, had progressed to the point that the authenticity and security of such signatures was sufficient. And finally, the pandemic changed work dynamics necessitating change.

Compare that scenario to the one Coinbase, and other participants in the cryptoeconomy face. As Coinbase and other observers tell it, the Commission’s position on digital asset regulation and cyrpomarkets has been a moving target at best. For example, just last week footage surfaced of now-SEC Chair Gensler lecturing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (“MIT”), where he taught, during which he says that Ethereum, the second largest cryptocurrency after Bitcoin by market cap, is “not a security.” And while he may have been making those statements as a professor and based on his understanding of the SEC’s position at the time, it still stands in stark contrast to his recent testimony before the House Financial Services Committee where he stated that “the vast majority of crypto tokens are securities” and because of that “crypto intermediaries are transacting in securities and have to register with the SEC.” Since Coinbase filed its mandamus action, Chair Gensler has reiterated these positions in his “Office Hours” video series. But as Coinbase, and others have pointed out, the SEC has not told the industry how that can be accomplished.

That is not from a lack of effort on the part of cryptoeconomy participants to get the SEC to commit to a regulatory position. Since January 1, 2018, the SEC has received five petitions for rulemaking seeking clarity on the relationship between the Securities and Exchange Acts’ authority and regulating aspects of the cryptoeconomy.[10] One additional rulemaking petition touching on the cryptoeconomy has been pending for over six years. None of these rulemaking petitions have been acted on. So, while the Coinbase’s petiton for rulemaking has not been pending that long, when considered along with other neglected SEC rulemaking petitions seeking agency direction, the Commission has been on notice for at least six years that individuals and businesses are interested in seeking clarity on its positions relative to regulating the cryptoeconomy.

The data assembled above show that the SEC has a clear pattern and practice of ignoring petitions for rulemaking. And while the “why?” for this behavior is not clear, Coinbase’s theory—that by indefinitely delaying action, the SEC can avoid judicial scrutiny—feels right. For administrative law practitioners and those interested in the APA section 553(e) and agency clarity and accountability, Coinbase’s mandamus action is one to watch.

Kara McKenna Rollins is Litigation Counsel at the New Civil Liberties Alliance.

[1] A search of Westlaw for “(‘petition for rulemaking’ or ‘rulemaking petition’ or ‘553(e)’) & +mandamus” across all federal courts returned twenty-one results, only three of which appear to be petitions for writ of mandamus related to a petition for rulemaking filed with an agency pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), but none of which share the same procedural posture as In re Coinbase Inc.—requesting issuance of writ based on agency’s unreasonable delay in taking any action on a rulemaking petition.

[2] Information regarding the petitions submitted to the SEC from January 1, 2018 until April 28, 2023 was extracted from the SEC’s database and reviewed for this post. Information for all petitions, and their accompanying information and descriptions, received between January 1, 2018 and April 28, 2023 was extracted and entered into Excel, where it was formatted for review. A copy of this data is on file with the author. Due to the inability to receive, propose, or promulgate half a rule, all averages in this post are rounded down.

[3] These statistics are derived from a search of the Federal Register’s database using its “Advanced Search” function for rules promulgated by the Securities and Exchange Commission and published in 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022.

[4] These statistics are derived from a search of the Federal Register’s database using its “Advanced Search” function for rule proposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission and published in 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022.

[5] These statistics are derived using the same methodologies described above for the year 2023.

[6] The New Civil Liberties Alliance (“NCLA”), where the author is employed, has submitted, or joined in submitting, three petitions for rulemaking to the SEC since July of 2018. See SEC File Nos. 4-761, 4-733, 4-726. The Commission has acted on none of these petitions.

[7] NCLA is counsel to the appellant in that matter.

[8] For purposes of this post, a substantive response is one which may be deemed a final agency action, i.e., the SEC made some clear indication that it was or was not taking a particular action proposed in a rulemaking petition or its action was in some way responsive to a rulemaking petition.

[9] This statistic was derived from a search of the Federal Register’s database using its “Advanced Search” function for the rulemaking petitions’ file numbers in all rules, proposed rules, and notices by the Securities and Exchange Commission and published since January 1, 2018. Data is on file with the author.

[10] This statistic is derived from a search of the SEC’s rulemaking petition database for the terms “crypto,” “cryptocurrency,” “digital asset,” “non-fungible token,” “NFT,” “Bitcoin,” and “blockchain.” See SEC File Nos. 4-789(Coinbase), 4-782, 4-771, 4-743, 4-736.