Mexican Gulf Fishing v. Department of Commerce: Part I

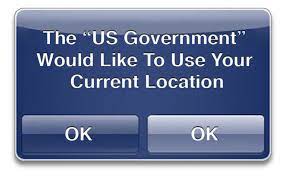

On July 21, 2020, the National Marine Fisheries Service (“NMFS”) published a rule requiring owners and operators of for-hire vessel operating in the Gulf of Mexico to submit electronic fishing reports upon their return to port “prior to removing any fish from the vessel” (or within 30 minutes if no fish had been retained). Even more controversially, the Rule required operators of such charter vessels to purchase, “permanently affix[] to the vessel” and maintain, a GPS device that constantly archived the vessel’s locations. The operator had to allow NMFS and Coast Guard fisheries enforcement personnel to access the information.

A group of charter boat captains and owners challenged the regulation, Mexican Gulf Fishing v. Department of Commerce, Dkt. No. 20-2312, 2022 WL 594911 (E.D. La. Feb. 28, 2022), appeal filed, Dkt. No. 22-30105 (5th Cir. March 4, 2020). In an opinion ranging far and wide over various administrative law doctrines, the District Court upheld the regulation. In upholding the tracking requirement, the focus of this post, the Court discussed the Supreme Court’s most recent major administrative search case, Los Angeles v. Patel, 576 U.S. 409 (2015).

For those counting, this is my 100th post as a regular blogger on Notice & Comment.

Regulatory Background

The Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (“MSA”) establishes a program to conserve and manage of fishery resources within 200 nautical miles of the United States coastline. NMFS is responsible for managing fishery resources, assisted by eight Regional Fishery Management Councils. Each Council possesses authority over a specific coastline, such as the Coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

The MSA requires the NMSF to manage the nation’s ocean fisheries by way of “fisheries management plans [(“FMPs”)].” Such plans must include, inter alia, “necessary and appropriate” measures “to prevent overfishing and rebuild overfished stocks, and to protect, restore, and promote the long-term health and stability of the fishery.”

The appropriate regional council will typically recommend amendments to update FMPs as needed, by submitting the proposed amendments to the NMFS. NMFS reviews the proposals, and then initiates and manages the “notice and comment” process specified in the Administrative Procedure Act (“the APA”).

On May 23, 2017, the Gulf Council proposed amendments to the Gulf Coast fisheries plan that included the tracking requirement. On October 26, 2018, NMFS published a notice of proposed rulemaking implementing the amendment and proposing to collect information from “for-hire” charter boats in the Gulf.

After reviewing comments submitted on the proposed amendments, NMFS published the Final Rule. Fisheries of the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and South Atlantic; Electronic Reporting for Federally Permitted Charter Vessels and Headboats in Gulf of Mexico Fisheries, 85 Fed. Reg. 44,005 (July 21, 2020). Though it adopted the electronic-fishing-report and tracking requirements as proposed, it responded to the comments submitted.[1]

The Tracking Rule

The tracking rule required that each permitted vessel be equipped with NMFS-approved hardware and software with a minimum capability of archiving GPS locations once per hour, 24 hours a day, every day of the year. Mexican Gulf Fishing, supra, slip op. at 14. Permit holders were responsible for purchasing the devices. The Final Rule included two exceptions. First, an in-port exemption allowed docked vessels to transmit location data only every four hours. Second, a power-down exemption suspends the requirement for vessels out of the water for more than 72 hours. Id. at 14-15.

Several commenters raised Fourth Amendment objections to the tracking requirement:

Providing all confidential transiting details is a violation of our 4th Amendment right to privacy and not necessary to manage the fishery. Such details are considered confidential by NOAA and utilized by other agencies not associated with management of the fishery. . .. . [T]o require detailed GPS data for vessels utilized by the for hire community is not necessary for fishery management purposes, flawed if used for fishery management purposes due to the climatic shift of our stocks and is also a violation of our 4th Amendment rights.

Id. at 15 (emphasis added).

NMFS did not explicitly discuss the Fourth Amendment, but did respond to the commenters’ concerns regarding the manner in which NMFS would protect the data, and prevent its misuse by staff and its public distribution. Id. at 16

Other commenters expressed different, but related concerns. First, they argued that 24-hour GPS surveillance was unnecessary and unduly burdensome. Second, they asserted that subjecting charter boats to tracking requirements equivalent to those imposed upon commercial fishing vessels was unnecessary and inappropriate. Third, they complained that the financial costs of compliance, namely purchasing, installing, and operating GPS-tracking devices, was an excessive and unwarranted burden upon the charter boat industry. Id. at 16-17.

The Legal Challenges to the Tracking Rule

On August 20, 2020, approximately one month after the rule had been published, the charter boat captains and owners filed suit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana asserting constitutional violations and seeking APA review. In an opinion rendered a day before the tracking rule was to go into effect, the Court dealt with the array of challenges mounted by the charter boat owners and operators. Among them were the following.

- The MSA did not authorize imposition of such a requirement.

- To the extent that the MSA allowed imposition of such a requirement, Congress had violated the non-delegation doctrine.

- To the extent that the MSA allowed imposition of a requirement to purchase GPS-location equipment, Congress had exceeded its Commerce Clause powers.

- The tracking requirement violated the Regulatory Flexibility Act.

- The tracking requirement was arbitrary and capricious, and thus subject to vacatur pursuant to the APA, because the requirement unnecessarily duplicated the obligation to file electronic fishing reports.

- The tracking requirement violated the captains’ and vessel owners’ due process rights.

- The GPS-location equipment requirement violated the Fourth Amendment.

This post will discuss the Court’s resolution of the Commerce Clause, APA, and Fourth Amendment issues.

The Commerce Clause Issue

In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519 (2012)(NFIB v. Sebelius), the Court distinguished the power to require an entity to engage in commerce from the power to regulate commerce. The Court held that Congress lacked the power to “compel[] individuals to become active in commerce by purchasing a product.” Id. at 554. Plaintiffs argued that by requiring them to purchase and install GPS tracking equipment NMFS had compelled them to engage in commerce, running afoul of NFIB v. Sebelius. Mexican Gulf Fishing, supra, slip op. at 42.

The Court noted that “multiple courts have rejected similar arguments.” Id. For example, in Relentless Inc. v. U.S. Department of Commerce, 561 F.Supp.3d 226, 243-44, 2021 WL 4256067, at *7 (D. R.I. 2021), the court held that industry funding of at-sea monitors did not compel members of the industry to participate in commerce, namely the at-sea monitor market, because they were voluntary participants in the industry subject to regulation. Id. at 42-43. Indeed, it explained, the relevant market was “the commercial herring fishing market” not the “monitoring market.” Id. at 43; accord, Goethel v. Pritzker, No. 15-cv-497-JL, 2016 WL 4076831, at *4-5 (D.N.H. July 29, 2016), aff’d on other grounds sub nom. Goethel v. U.S. Dep’t of Com., 854 F.3d 106 (1st Cir. 2017).

Similarly, the Court concluded, plaintiffs are voluntary participants in the charter vessel permit program. As such, Congress had ample power to regulate them, “even if such regulation imposes costs.” Id. at 43-44.

The APA Issue

Plaintiffs’ APA challenge focused on NMFS’s failure to respond to several comments raising Fourth Amendment objections to the proposed regulation. The Government countered that NMFS reasonably interpreted the comments as raising issues regarding inappropriate data sharing, and had sufficiently responded to those concerns. Id. at 45.

The Court noted that four commenters had employed identical language in raising their Fourth Amendment concerns: “Providing all confidential transiting details is a violation of our 4th Amendment right to privacy and not necessary to manage the fishery. Such details are considered confidential by NOAA and utilized by other agencies not associated with management of the fishery.” Id. The Court noted that NMFS had addressed the commenters’ data protection concerns by explaining how it would “protect these data in accordance with applicable law.” Id.

The Court concluded that NMFS’s interpretation of and response to the comments was reasonable, even though NMFS had not explained the legal basis for its conclusion that the tracking rule was consistent with the Fourth Amendment constraints on warrantless searches. See, id. at 46.

In large part, the Court faulted the commenters for the vagueness of their comments, concluding that the commenters had inadequately raised their Fourth Amendment objections. The Court observed that commenters must “disclose the factual or policy basis on which [his or her comment] rest[s][.]” Agencies had no obligation to “sift pleadings and documents to identify arguments that are not stated with clarity.” Indeed, “[j]ust as the opportunity to comment is meaningless unless the agency responds to significant points raised by the public, so too is the agency’s opportunity to respond to those comments meaningless unless the interested party clearly states its position.” Id.

The Court asserted that the only basis the commenters’ had cited for their privacy objections was the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency’s (NOAA) treatment of vessels’ “transiting details” as “confidential.” NMFS had addressed that particular concern and “was not required to dig for another basis of generalized Fourth Amendment concerns.” Id.

The Court supported its approach by analogizing to an Eleventh Circuit case, Hussion v. Madigan, 950 F.2d 1546 (11th Cir. 1992). There, the Eleventh Circuit had refused to find that “the [a]gency’s limited acknowledgment of general due process concerns evince[d] an ‘entire[ ] fail[ure]’ to consider them,” given that the agency had addressed specific due process concerns raised by commenters. Id. at 46.[2] As in Hussion, NMFS addressed the specific confidentiality objections, and was not “required to acknowledge general privacy objections that failed to provide another basis for their concerns.” Id. at 47.

Moreover, the Court explained, even if the commenters’ submissions could be viewed as sufficiently raising general Fourth Amendment concerns, NMFS and the Gulf Council had “considered the important aspects of the problem.” Id. at 47 (quoting Motor Vehicle Ass’n v. State Farm Mutual Auto. Ins., 463 U.S. 29, 43 (1983)). The Court noted that the proposed and final regulatory text actually took a more “conservative” approach than Gulf Council Data Collection Technical Committee. Id. at 49. The Technical Committee had recommended requiring a ping frequency of once every 30 minutes. NMFS had relaxed the requirement, merely requiring a minimum ping frequency of once per hour. Id. (citing 83 Fed. Reg. at 54,076, 54,078; 85 Fed. Reg. at 44,018, 44,020).

In the Court’s view, the Final Rule’s preamble reiterated NMSF’s finding that the tracking requirement minimized the burden on the industry. Id. (citing 85 Fed. Reg. at 44,012). The Court concluded that the rulemaking record, viewed in its entirety, id. at 47-48 (citing Thompson v. Clark, 741 F.2d 401, 409 (D.C. Cir. 1984)), showed that concerns about privacy and the burden on the industry “were considered throughout the rulemaking process and affected the ultimate provisions of the Final Rule.” Id.

Moreover, the Court noted the D.C. Circuit’s reasoning in Aeronautical Repair Station Association v. FAA, 494 F.3d 161, 173 (D.C. Cir. 2007). There the D.C. Circuit had explained that the sufficiency of an agency response to commenters’ assertions that drug testing would violate the Fourth Amendment, should be considered in light of past agency resolutions of the same or similar issues.[3] The District Court asserted that NMFS had “repeatedly note[d],” in the course of addressing various commenters concerns about the tracking requirement in the Final Rule’s Preamble, that tracking equipment has been required for commercial vessels with Gulf reef fish permits since 2006.” Id. (citing 85 Fed. Reg. at 44,007, 44,012-13).[4] Moreover, the District Court said, the Final Rule’s discussion of the longtime tracking requirement for commercial fishing vessels shows NMFS considered the regulatory norms for the fishing industry and types of burdens it ought to impose. Id.[5]

Plaintiffs also asserted that NMFS had failed to respond to several comments regarding the necessity, burden, and cost of the tracking requirement. In their view, NMFS’s reasons for imposing the tracking requirement were conclusory and lacked an adequate cost-benefit analysis. The Government argued that the Final Rule “had explain[ed] the need for the tracking requirement and that NMFS had carefully considered the costs of the tracking requirement compared to a charter vessel business’s income.” Id. at 50.

The Court again sided with the Government. It found persuasive the Final Rule’s explanation of the “unique validation the tracking requirement adds”: “The Gulf Council adopted the requirement that the tracking equipment be permanently affixed to the vessel in order to know the position reported is actually the vessel, as opposed to an unrelated position anyone could otherwise submit.” Id. at 51-52.

Summarizing its more extensive analysis, the Court asserted that NMFS had “appropriately responded to the comments it received regarding the necessity, burden, and costs of the tracking requirement.” In particular, it had “identified a unique benefit of the tracking requirement.” NMFS had “considered the burdens the tracking requirement would impose on smaller charter vessels and conducted a thorough analysis of the costs.” The agency had “compared the costs and benefits of the selected equipment to that of [several] alternatives.” And the NMFS had struck a balance between the competing considerations, “rejecting the no-action alternative that provided the least burden but little benefits as well as real-time tracking alternatives that would have provided the most benefits but also the most burden.” Id. at 56.

The Fourth Amendment Issue

The Court ultimately reached the core question, whether the tracking requirement violated the Fourth Amendment. “[A]ssum[ing] without deciding” that the required transmission of tracking data constituted a Fourth Amendment search, and was thus subject to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement, the Court found the tracking requirement permissible under “the closely regulated industry exception” to the that requirement. Id. at 63

That analysis required two steps. Id. at 63-64. First, the Court had to determine whether the fishing industry qualifies as a closely regulated industry. Id. If so, second, the Court had to assess whether the tracking program satisfied the three criteria laid out in New York v. Burger, 482 U.S. 691 (1987), which require the presence of: “(1) a substantial government interest, (2) a regulatory scheme that requires warrantless searches to further the government interest, and (3) ‘a constitutionally adequate substitute for a warrant.’” Id. at 702-03; Mexican Gulf Fishing, supra, at 64.

Is the Industry Closely-Regulated?

The Court had little difficulty finding that the fishing industry qualified as heavily regulated. In doing so, the Court laid out the “long history” of fishing industry regulation. Id. at 64-67. Such regulation predated the Constitution’s adoption. Id. at 65.[6] The MSA itself, which has been in effect since 1977, specifically authorizes warrantless searches. And dozens of categories of vessels are required to have tracking equipment by applicable regulations. Id. at 66.

Moreover, the Court observed, numerous courts have recognized that because “[t]hose who venture on the seas are presumed to do so cognizant of the raft of regulations designed to promote their safe passage . . ., the ‘reasonable’ expectation of privacy is often less aboard a vessel than on land.” Id. at 67 (quoting United States v. Ortega, 644 F.2d 512, 514 (5th Cir. 1981)).

Plaintiffs argued that City of Los Angeles v. Patel compromised the validity of the such caselaw. Plaintiffs read Patel to limit the closely regulated industry doctrine to industries that “pose[ ] a clear and significant risk to the public welfare.” Id. at 69.

The Court dismissed plaintiff’s argument as grounded in “an overly broad reading of Patel.” Patel had stated that “risk to the public welfare is one factor to consider when determining whether an industry is closely regulated, but it is not the be-all and end-all.” Id. at 69 (emphasis added). And several post-Patel lower court opinions confirm that more narrow reading of the case. Id. at 70.

Nevertheless, the Court identified a risk to the public welfare that weighs in favor of classifying the fishing industry as closely regulated. The findings in the MSA itself amply showed Congress’ fear that the “fishing industry, if left unregulated, would overfish and deplete the United States’ fishery resources,” “endangering the public welfare by harming the nation’s food supply, economy, and health.” Id. at 72.

Does the Regulatory Regime Satisfy the Burger Criteria?

The Court then turned to its analysis of the three Burger criteria.

First, the Court explained, the Government has a substantial interest in protecting the fisheries, and most particularly preventing overfishing. Id.

Second, the tracking requirement is necessary to furthering that interest. It noted once again that the purpose of the tracking requirement is to “allow NMFS to independently determine whether the vessel leaves the dock.” Id. at 73.

Plaintiffs argued the tracking requirement merely duplicates information contained in the electronic reporting requirement. In their view, Patel had precluded warrantless searches intended merely to validate records maintained by a regulated entity. Id. Yet again, the Court found plaintiffs’ reading of Patel “overly broad.” Id. at 73-74. Patel had invalidated a municipal ordinance that authorized warrantless inspection of guest books maintained by hotel operators.[7] But, the District Court noted, Patel did not involve movements of vessels. And vessels’ locations cannot be verified once the vessel changes position. Id. at 74. “Fishermen may, whether deliberately or unintentionally, misstate the locations they fished in the electronic reports.” Id. at 75. Requiring a warrant or pre-compliance review would deprive the Government of the data it needs, the locations actually fished, leaving “no accurate way to verify the locations fishermen report.” Id.

Third, the tracking requirement provides a constitutionally adequate substitute for a warrant. To qualify as an adequate substitute, the regulatory regime must perform two basic functions: (1) “advis[ing] the commercial premises owner that the search is being made pursuant to the law and has a properly defined scope,” and (2) limiting inspecting officers’ discretion.” Id. at 77.

As to the “notice” requirement, the Court noted that other courts have held the provisions in the published regulations and statutes at issue may adequately serve that purpose. Id. The MSA itself notified charter boat owners that their data may be collected without a warrant. Id.[8] And the tracking requirement itself provides specific details on the data collection, such as who must participate, what is necessary to comply, and when the collection will occur. Id. at 79.

With respect to the second requirement, focused on cabining inspectors’ discretion, the Court observed: “While the statute must also limit the discretion of searching officers, it need not contain the most exacting limitations.” Id. at 78. The tracking requirement, it noted, involves no exercise of discretion at all; the search is the same as stated in the regulation each time.

But in addition, the Court highlighted three limitations upon the manner and scope of data collection. Id. at 79. First, location data is collected only once her hour. Second, the tracking requirement is limited to vessels participating in the federal charter vessel permit program. Third, access to the data is limited to NMFS, the Coast Guard, and their designees. Ultimately, the Court concluded, collection of location data is “not so random or infrequent that the vessel owner has no real expectation that his property will from time to time be inspected.” Id. at 79-80.

The District Court explained that the extent of the regulation of the industry is also relevant to assessment of the adequacy of an inspection scheme — “the pervasiveness and regularity of the federal regulation . . . ultimately determines whether a warrant is necessary to render an inspection program reasonable under the Fourth Amendment.” Id. at 80 (quoting Kaiyo Maru, 699 F.2d at 996, quoting (quoting Donovan v. Dewey, 452 U.S. 594, 606 (1981)). For decades NMFS and the FMPs “have established tracking requirements for numerous portions of the commercial fishing industry.” Id.

In Part II of this series, I will provide a few observations focused upon NMSF’s consideration of the Fourth Amendment issues to which commenters alluded.

[1] Subsequently, NMFS delayed the effective date of the tracking rule until March 1, 2022. Fisheries of the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and South Atlantic; Electronic Reporting for Federally Permitted Charter Vessels and Headboats in Gulf of Mexico Fisheries, 86 Fed. Reg. 60,374, 60,374 (Nov. 2, 2021).

[2] Hussion involved regulations meant to “streamline” eviction proceedings in a Farmers-Home-Administration-funded housing project. Several commenters complained that the regulations deprived them of their constitutional due process rights. The agency addressed several specific concerns raised, such as “self-help evictions” and state court “rubber-stamping of unwarranted eviction decisions.” However, the Farmers Home Administration (“FmHA”) had not specifically acknowledged the commenters’ more “general due process concerns.” The Hussion court held that the agency’s responses were sufficient, reasoning “[t]he APA does not require the Agency to respond to comments which, in essence, reflect a policy-based preference for the most exacting guarantees of due process over the interest shared by owners and other tenants in minimizing the cost and delay of good-cause evictions.” Rather, the agency need address only the specific “significant objections raised,” by commenters.” Id. at 46-47.

[3] The D.C. Circuit observed that more than 15 years previously the FAA had resolved issues regarding drug testing’s privacy implications when the agency had adopted a drug testing regulation that “carefully balanced the interests of individual privacy with the Federal government’s duty to ensure aviation safety.” Given that, the D.C. Circuit had concluded that the FAA’s succinct responses to comments concerning privacy and Fourth Amendment were adequate.

[4] NMFS seems to have literally made the comment twice, which I suppose technically qualifies as “repeatedly.” Even so, the comments were not made in the context of addressing privacy concerns, but rather made in response to comments that the GPS systems might drain vessel’s batteries or might be impractical for small craft.

[5] Here the Court does not provide a citation; quite unusual for an opinion with such extensive citations. The term “commercial” is used 31 times. The most appropriate references in support of this point in terms of intrusions into privacy, on page 44007, are not particularly cogent. On that page, NMFS observed: “This final rule has similar requirements for powering down a cellular or satellite VMS unit that currently apply to vessels in the commercial reef fish fishery.” Later on that page, it notes: “In the Gulf, an owner or operator of a federally permitted commercial reef fish vessel is already required to have a satellite VMS unit permanently affixed to the vessel.”

[6] Indeed, “the expectation of finding the game warden looking over one’s shoulder at the catch is virtually as old as fishing itself.” Id. (quoting Lovgren v. Byrne, 787 F.2d 857, 865 (3d Cir. 1986)). The Federal Government has regulated fishing since at least 1793, when Congress enacted the Enrollment and Licensing Act of February 18, 1793. Id. That Act granted licenses for the fishing of certain categories of fish,” and “allowed government officials to search of licensed vessels.” Id. The Court noted that “[r]egulation of the fishing industry has continued throughout U.S. history.” Id.

[7] The Patel Court had held warrantless searches unnecessary because the expeditious nature of the required “precompliance review would . . . [not] giv[e] operators a chance to falsify their records.” Id. at 74 (citing Patel, 576 U.S. at 427). The Patel Court had explained that “[a]n officer could still ‘conduct[ ] a surprise inspection by obtaining an ex parte warrant or, where an officer reasonably suspects the registry would be altered, . . . guard[ ] the registry pending a hearing on a motion to quash.’” Id. In essence, the District Judge explained, the records at issue in Patel “were not going anywhere.” Id.

[8] The MSA specifically allows officers to “access, directly or indirectly, for enforcement purposes any data or information required to be provided under this subchapter or regulations under this subchapter, including data from vessel monitoring systems, satellite-based maritime distress and safety systems, or any similar system.” Id. at 78-79.