Agency Adjudication and Congress’s Anti-Removal Power

*This is the ninth post in a symposium on the decisional independence of administrative adjudicators. For other posts in the series, click here.

There is a growing concern in administrative law circles, and especially among administrative law judges and other agency adjudicators, that the decisional independence of agency adjudicators is increasingly being threatened. At least formally, the decisional independence Congress imagined when it enacted the Administrative Procedure Act seems to have eroded—for two independent reasons.

First, as Emily Bremer sketches out in the introductory post to this symposium, the vast majority of agency adjudicators are not even administrative law judges (ALJ) that have the hiring and tenure protections provided by the Administrative Procedure Act. Melissa Wasserman and I chronicle this evolution of agency adjudication across the federal regulatory state in The New World of Agency Adjudication.

Second, as Richard Levy and Robert Glicksman explain in their contribution to the symposium (as do other contributors), the Supreme Court in recent years has embraced a more unitary executive view of separation of powers and the Appointments Clause. For instance, in Lucia v. SEC, the Court held that administrative law judges are at least inferior offices under the Appointments Clause, such that they must be appointed by the agency head, instead of through a more merit-based civil-service selection process.

In United States v. Arthrex, the Court last Term held that administrative patent judges, as officers appointed by the agency head for Appointments Clause purposes, would violate the separation of powers if they had both final decision-making authority and tenure protections. The Federal Circuit had remedied the constitutional infirmity by stripping the adjudicators of tenure protections, which would be potentially bad for decisional independence. The Supreme Court, conversely, struck down the statutory prohibition on agency-head review. In so doing, the Court reaffirmed the standard federal model for agency adjudication where the trial-level adjudicator makes the initial decision with tenure protection and the political-appointee agency head gets final say.

The next case in this line of precedent will be about removal, and whether the agency head (or the president) must be able to more easily fire agency adjudicators—i.e., whether the agency head can fire them for cause. Last spring, in Fleming v. USDA, the D.C. Circuit dodged the issue on procedural grounds, but Judge Rao’s dissent gets to the merits and explains how under Supreme Court precedent the agency head must be able to fire an administrative law judge for cause. Last month the Court granted cert in a case that presented the question—Axon Enterprise v. FTC—but it declined review on that question.

If the Court eventually ends up agreeing with Judge Rao, Congress will have one fewer tool to create a measure of agency adjudicator decisional independence. In particular, Congress will no longer be able to design a statutory framework that requires a merit-based system to determine whether to fire or otherwise discipline an administrative law judge or other agency adjudicator.

That doesn’t mean Congress is without tools to create at least a measure of decisional independence. I surveyed those proposals in a Regulation essay last spring, and this symposium explores a number of them in much greater detail. To be candid, many of those proposals do not strike me as being very feasible or effective. For instance, I agree with Ron Levin’s take about the federal central panel model (which Glicksman and Levy introduce and then defend in this symposium). I won’t repeat Ron’s doubts in this post.

I should underscore one critical point, as it contrasts the central panel proposal with the anti-removal power approach I suggest below: Glicksman and Levy (and others) have made the formal case that there could be a potential threat to decisional independence of agency adjudicators based on the two developments noted above. But no one has empirically explored in any rigorous manner whether there is a systemic, real-world threat to decisional independence—whether agency adjudicators make decisions based on political influence and out of fear of being fired or otherwise politically disciplined, instead of based on law and facts. Before we suggest Congress should move potentially more than 12,000 agency adjudicators from their current agencies into one mega central panel agency, we should better understand the scope and magnitude of the problem that the reform proposal seeks to address.

We should, of course, also study carefully the direct and indirect effects of such a dramatic reform of the administrative state. Congress, agencies, and the public have spent decades trying to improve agency-specific adjudication systems—to increase inter-decisional consistency, to improve the quality of adjudicator decision-making, to speed up the adjudication process, to manage crushing backlogs, and to help individuals who often appear without legal counsel to effectively navigate those systems. To provide just one example, as Matt Wiener and I chronicle in a recent study for the Administrative Conference of the United States, agencies have carefully developed appellate review systems to help address these systemic challenges in their high-volume adjudication systems.

I hope reformers will pause and do the hard empirical work of examining the intended and unintended consequences of bold reform proposals, such as relocating thousands of agency adjudicators to a new federal agency. Based on my decade of studying agency adjudication systems at the federal level, I fear such empirical work would reveal that these bold reform proposals would produce insubstantial benefits that would come nowhere near justifying staggering costs to the system. And the millions of individuals who try to navigate these adjudication systems each year, I fear, would bear the brunt of those costs.

By encouraging further empirical study and cautioning against bold systemic reform, however, I do not mean to suggest that Congress and federal agencies should just do nothing in the interim. Instead, Congress should start exploring now how to better use its “anti-removal power” to enhance decisional independence of agency adjudicators. (I also agree with Kent Barnett that the Biden Administration can and should consider implementing impartiality regulations.)

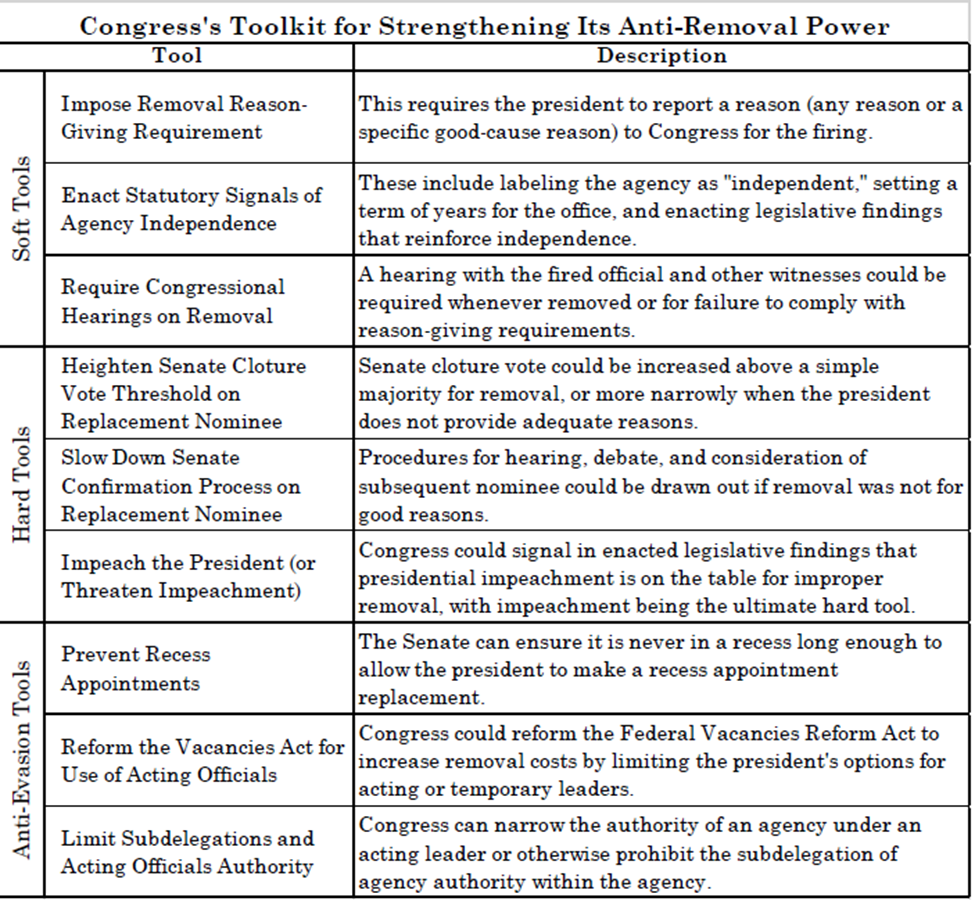

Aaron Nielson and I develop this argument in much greater detail in a new draft paper, Congress’s Anti-Removal Power. Part III of the paper outlines the various tools Congress has to raise the president’s removal costs, illustrated in the table below. Part V.B then presents the case study, summarized below, of how Congress can use this toolkit to address decisional independence in agency adjudication.

In particular, we argue that if Congress wants to address such decisional independence, the “soft tools” in our proposed congressional toolkit (depicted in the table above) would be particularly effective.

First, Congress could embrace statutory signals of decisional independence by enacting legislative findings on the importance of decisional independence, the expert-based qualifications for hiring, and the appropriate (and inappropriate) reasons for firing. These enacted legislative findings would not be statutory commands, but aspirations and expectations—signaling to the president, the agency, and the public that Congress cares about decisional independence in agency adjudication.

Second, Congress could require the agency head to provide Congress with reasons—indeed, good reasons—for firing an agency adjudicator. This isn’t a new tool. Congress has required that of the president for the Comptroller of the Currency and inspector generals. But it raises the cost of removal on the agency head by forcing the agency head to reveal the reasons for the firing publicly and to Congress, to be judged in the court of public opinion and by the agency’s congressional overseers.

Third, Congress could pre-commit by statute to hold an oversight hearing if the agency head fires an agency adjudicator, or perhaps only if the agency head fails to provide the statutorily required (good) reason. At that hearing, the fired adjudicator and agency head would testify, as well as any other witnesses the committee wanted to call, such as the head of the adjudicator’s union. This hearing would raise the removal costs even more, as agencies are quite receptive to congressional oversight. To be sure, the end result would not remove an agency head’s formal power to fire an agency adjudicator. It would often just make such a firing too politically costly for the agency head, especially if the firing is not based on merit.

Fourth, for some agency adjudicators—perhaps appellate-level adjudicators like those at the Board of Immigration Appeals—Congress could, per the Appointments Clause, require them to be presidentially appointed on advice and consent of the Senate. Rebecca Eisensberg and Nina Mendelson suggest that as a potential option to address patent adjudication after United States v. Arthrex—i.e., by creating a panel of Senate-confirmed final decisionmakers. It would be infeasible to require a lot of agency adjudicators to be Senate confirmed, which is one problem with creating an Article I immigration court or replacing agency adjudication with Article III administrative courts. But one could imagine Congress exploring this anti-removal tool with respect to a subset of appellate adjudicators to create an additional measure of decisional independence.

Returning to the core “soft tools” proposal, however, the reason-giving and congressional hearing approach has the added benefit of keeping Congress appraised and focused on the issue of decisional independence in agency adjudication. If the threat against decisional independence were grave or widespread, the congressional hearings and oversight would help uncover and assess it. This proposal would also avoid the massive costs and unintended consequences of the bolder reform proposals. It would keep the agency adjudication systems in place, and only raise the removal costs on the agency head. In other words, pursuing reform through Congress’s anti-removal power would be a substantially less-invasive option, which is all the more important in an area with so much empirical uncertainty as to the scope of the problem and the impacts of the broader reform proposals.

There is and should be bipartisan support in Congress to protect the decisional independence of agency adjudication. As Congress explores the various options presented in this symposium and elsewhere, I hope it will consider how best to use its anti-removal power as part of any potential solution.

Christopher J. Walker is the John W. Bricker Professor of Law at The Ohio State University.