The CFPB’s Blank Check—or, Delegating Congress’s Power of the Purse

In one of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s first strategic plans, the then-new agency highlighted Congress’s decision to vest it with a completely independent source of revenue: “providing the CFPB with funding outside of the congressional appropriations process,” Congress had “ensure[d] full independence” for the agency.

The agency’s declaration of independence from future congressional appropriations echoed the Senate Banking Committee’s own explanation of the new agency’s power just a few years earlier. “The Committee finds that the assurance of adequate funding, independent of the Congressional appropriations process, is absolutely essential to the independent operations of any financial regulator.” Unlike other financial regulators who must seek appropriations from Congress, the CFPB would not be “subject to repeated Congressional pressure.”

But in constitutional government, is an agency’s “full independence” from Congress such an unvarnished good? Last month, the Fifth Circuit answered this question with a resounding “no.” In Community Financial Services v. CFPB, the court held that the CFPB’s independent budget violated the Constitution’s provision that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.”

It is an interesting decision and perhaps destined for review by the Supreme Court, which has never fully ventilated the Appropriations Clause’s original meaning. The CFPB itself certainly wants the Court to take up the issue, as seen in its new cert petition.

So here are a few of my own observations, based in part on my work many years ago, while still in private practice, when my former colleagues and I were among the first to question the CFPB’s novel funding structure in litigation. (See, e.g., here, here, and here.)

1. The CFPB’s Power of the Purse

Congress gave the CFPB sweeping authority to fund itself, freeing the agency from the necessity of getting appropriations from subsequent Congresses. Specifically, Section 1017 of the Dodd-Frank Act (12 U.S.C. § 5497) empowers the CFPB to simply demand hundreds of millions of dollars from the Federal Reserve, up to 12 percent of the Fed’s annual operating expenses.

Thus, the entire funding process is removed from Congress. Indeed, Section 1017 adds that the CFPB’s self-funded budget “shall not be subject to review by the Committees on Appropriations of the House of Representatives and the Senate,” nor subject to “the consent or approval of the Director of the Office of Management and Budget.”

For a sense of the scope of this power, in 2022, the Fed budgeted its operating expenses at more than $7.5 billion. The CFPB’s twelve-percent cut is approaching $1 billion annually. Recently the CFPB estimated its funding authority as “$717.5 million in FY 2021,” “$734.0 million in FY 2022,” and “750.9 million in FY 2023.”

It is an astonishing power, both in theory and in practice. The CFPB Director determines how much money the agency needs, and he sends a one-page letter directing the Federal Reserve Chairman to transfer hundreds of millions of dollars to the CFPB. Then the Federal Reserve replies a few days later with a one-page letter confirming that the payment was made: “Please do not hesitate to contact me if you have any questions or concerns about the Bureau fund or future funding requests,” the Fed’s chief financial officer adds politely. (You can see the agencies’ correspondence over the years here.)

These transfers to the CFPB come ultimately from the Treasury, because they reduce the surplus that the Fed is otherwise obligated to remit to the Treasury under 12 U.S.C. § 289(a)(3)(B).

2. Constitutional Principles and a Court’s New Decision

Years ago, Chief Justice Roberts quipped that the Constitution’s authors “could hardly have envisioned today’s ‘vast and varied federal bureaucracy’ and the authority administrative agencies now hold over our economic, social, and political activities … ‘[T]he administrative state with its reams of regulations would leave them rubbing their eyes.’”

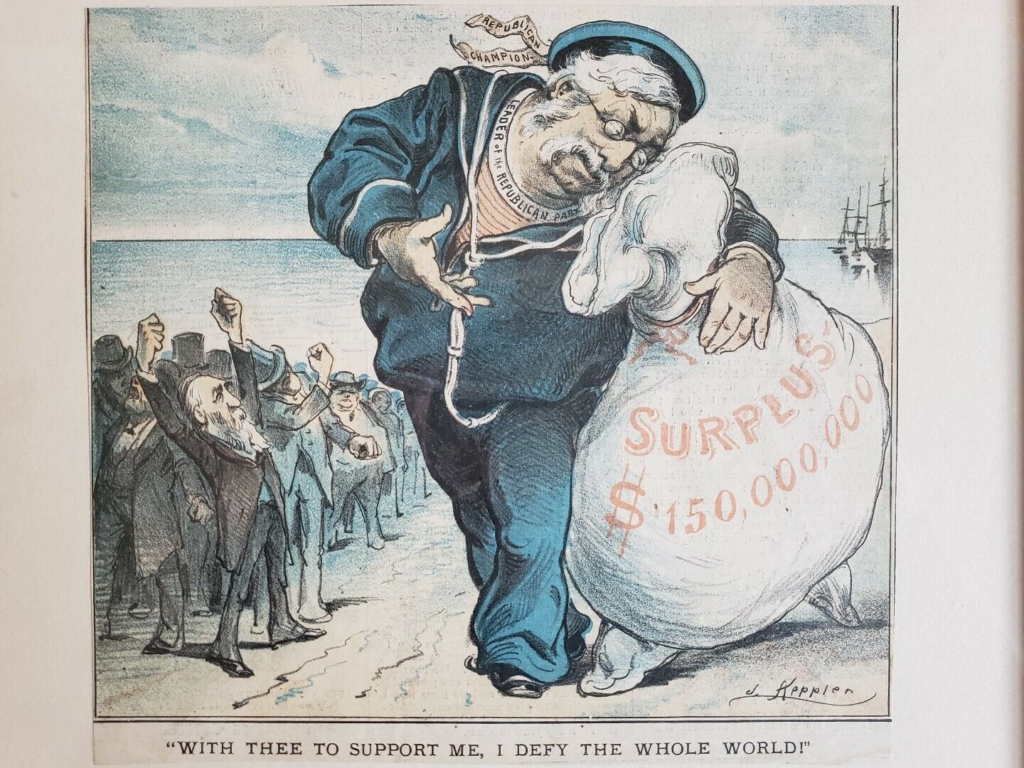

They might have a similar reaction to the CFPB’s power and discretion to simply claim such enormous sums of money for itself. For the founders knew the fundamental constitutional importance of Congress’s “power of the purse.”

James Madison and Alexander Hamilton emphasized this from the start. “This power over the purse,” Madison wrote in The Federalist, “may, in fact, be regarded as the most complete and effectual weapon with which any constitution can arm the immediate representatives of the people[.]” And he reminded us of England’s history, where the power of the purse was the best tool for resisting “all the overgrown prerogatives of the other branches of the government.” Hamilton, too, understood the importance of this power. He recognized in The Federalist that while the executive branch “holds the sword,” Congress “commands the purse.” And as he added bluntly in a letter, “that power which holds the purse-strings absolutely, must rule.”

This belief in the importance of the power of the purse is ultimately reflected in Article I, Section 9, Clause 7 of the Constitution: “no money shall be drawn from the treasury, but in consequence of appropriations made by law.” The Fifth Circuit applied those principles, and that constitutional provision, in its recently landmark decision against the CFPB.

A few months earlier, Judge Edith Jones had published a concurring opinion in another case, questioning the CFPB’s constitutionality. Her colleagues adopted her views in their opinion for the Court last month in Consumer Financial Services v. CFPB, a challenge to the CFPB’s 2017 payday lending rule. The Fifth Circuit held that the CFPB’s rule was unlawful because the CFPB itself is unconstitutional, due to its “self-actualizing, perpetual funding mechanism” outside of the appropriations process prescribed by the Constitution—a problem made all the worse by the agency’s “capacious portfolio of authority.” An agency with such immense power, freed from Congress’s power of the purse, simply “cannot be reconciled with the Appropriations Clause and the clause’s underpinning, the constitutional separation of powers.”

3. The Fifth Circuit and “Appropriations”

The crux of the issue, as the Fifth Circuit saw it, is whether the CFPB’s perpetual power to independently fund itself without resort to Congress violates Article I’s Appropriations Clause. It’s a profoundly important question, but not a simple one; as I noted at the outset, the Court has never grappled fully with the Appropriations Clause’s original meaning or its implications for modern governance.

On this blog, Prof. Zach Price drew recently from his own thoughtful scholarship, concluding that the CFPB’s funding structure is “bad but constitutional.” (His verdict calls to mind Justice Scalia’s famous stamp.) Prof. Price concludes that the CFPB’s funding actually does come from “appropriations made by law”—that is, from Dodd-Frank itself. “Congress has provided authority by statute for the CFPB’s expenditures,” he writes. “Annual appropriations are generally a good idea,” he adds, “but there is no constitutional requirement that Congress employ them for this or any other civil agency.” This is the main thrust of the CFPB’s cert petition, too.

For what it’s worth, I disagree with my friend’s (and the CFPB’s) assessment of the case, and the broader constitutional issue, for a few reasons.

First, I think he frames the Fifth Circuit’s holding too narrowly. I do not read the Fifth Circuit (nor Judge Jones’s earlier opinion) as requiring the CFPB to be funded through annual appropriations. While the court notes that this is the normal practice (as Judge Jones notes, too), I do not think its opinion goes so far as to require an annual appropriations cycle. Rather, the court frames the problem in terms of the CFPB’s “perpetual” power to fund itself. If Congress had given the CFPB, say, a three- or five-year funding endowment, then perhaps the court would have seen the case differently; Dodd-Frank’s problem, as the Fifth Circuit saw it, is its permanent grant of perpetual funding power to the CFPB, freeing the agency from ever needing to return to Congress for new appropriations. (This difference goes to the heart of the constitutional problem, as I explain in the next section of this post.)

Second, and more importantly, while the question of what constitutes a constitutional “appropriation” is not easy, the CFPB itself has always described its own funding as not coming from “appropriations.”

From its earliest reports (including the one I quoted in my opening lines above), to the present day, it has recognized that its funding is not “appropriated.”

Take, for example, current CFPB Director Rohit Chopra’s latest financial report: he describes the CFPB as “an independent, non-appropriated bureau,” and then states (twice) that funds transferred from the Federal Reserve to the CFPB “are not government funds or appropriated funds.” (I’d quibble with the part about “government funds,” of course, given that the CFPB’s funds are ultimately subtracted from what the Federal Reserve would otherwise be required by law to transfer to the Treasury.)

(Update, December 4: For more examples of the CFPB describing its funds as not “appropriated,” see here.)

Third, and most importantly, I’m not convinced that Dodd-Frank’s Section 1017 itself, creating the CFPB’s perpetual self-funding power, is an “appropriation made by law.”

Though, again, this is no simple issue, and Price makes very good points. The Government Accountability Office’s Principles of Federal Appropriations Law, for example, seems to accord with Prof. Price’s broad view of “appropriations.” Citing prior opinions of the Comptroller General, the GAO concludes that if “the statute contains a specific direction to pay and a designation of the funds to be used, such as a direction to make a specified payment or class of payments ‘out of any money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated,’ then this amounts to an appropriation.” That description seems to resemble the CFPB statute.

But other GAO reports focusing more specifically on such issues suggest otherwise. Its 2016 report on “permanent funding authorities” explains that the CFPB’s and several other agencies’ funding “is provided by laws other than appropriation acts.” And GAO’s 2018 report, “Government-Wide Inventory of Accounts with Spending Authority and Permanent Appropriations,” makes no mention of the CFPB in its table of agencies with permanent appropriations.

I tend to think the latter view, which accords with the CFPB’s longstanding account of itself, is the more plausible one: year in and year out, the CFPB is claiming and spending federal money, ultimately from the Treasury, which does not come from constitutional “appropriations.” And if so, then the agency has a real constitutional problem on its hands, for all the reasons that the Fifth Circuit suggested, and perhaps more.

Because Congress’s constitutional power of the purse has not received as much attention in the courts over the years, these issues do not slot into decades-old judicial doctrines. That is no surprise, since Congress and the CFPB both understood that the agency’s funding structure was itself an exceptional break from the normal course of administration. But the absence of squarely-on-point judicial and legislative precedents makes it all the more interesting to watch how judges grapple with the constitutional issue. If the Supreme Court eventually hears a case challenging the constitutionality of the CFPB’s funding structure, how might the justices frame it?

4. A “Junior-Varsity Congress”

The more that I’ve thought about these issues over the last decade, the more that they remind me of Justice Scalia’s account of the Sentencing Commission in Mistretta v. United States. By granting the CFPB a perpetual power to determine its budget and claim those funds from the Fed, has Congress unconstitutionally delegated its power of the purse to the CFPB?

Justice Scalia was famously wary of nondelegation doctrines that attempt to judge the amount of policymaking discretion that an agency enjoys in the interpretation and enforcement of regulatory statutes. But in Mistretta he distinguished those cases from a different kind of “nondelegation” problem: Congress’s outright delegation of legislative power—not just interpretative discretion, but legislative power per se—to another body to administer in the first instance.

The constitutional problem in Mistretta, as he saw it, was not that the Sentencing Commission exercised some quasi-legislative power to make policy in the course of interpreting and enforcing vague laws; rather, the problem was that Congress had empowered the Commission to simply write laws from the ground up, separate from the enforcement of those laws.

Here is how he drew that distinction and framed the issue:

The focus of controversy, in the long line of our so-called excessive delegation cases, has been whether the degree of generality contained in the authorization for exercise of executive or judicial powers in a particular field is so unacceptably high as to amount to a delegation of legislative powers.

… In the present case, however, a pure delegation of legislative power is precisely what we have before us. It is irrelevant whether the [Commission’s sentencing rules] are adequate, because they are not standards related to the exercise of executive or judicial powers; they are, plainly and simply, standards for further legislation.

The lawmaking function of the Sentencing Commission is completely divorced from any responsibility for execution of the law or adjudication of private rights under the law.

Or, as he colorfully summed up: Congress had created “a sort of junior-varsity Congress,” to save Congress itself from having to carry out its own legislative responsibilities.

Has Congress done something similar here with the CFPB? I think so: Congress has fully delegated its power of the purse to the CFPB; the only limit on that purse is the Federal Reserve’s operating expenses, of which the CFPB can receive no more than 12 percent.

Within that nearly $1 billion limit, the CFPB director unilaterally determines how much money his agency should receive; he appropriates that money from the Fed (and thus from the surplus that would go to the Treasury); and then his agency can spend it as he sees fit.

In that respect, the CFPB’s delegated power is similar to the Sentencing Commission’s. The CFPB’s power of the purse is entirely separate from its power to make and enforce rules. Unlike the policymaking power that inheres in the agency’s enforcement discretion, its power of the purse is not simply a facet of enforcement discretion. The power of the purse entirely precedes enforcement activities—and that, as Madison emphasized, is the point.

To be sure, the CFPB does have vast policymaking discretion in its administration of substantive regulatory laws; the Sentencing Commission did not. But that makes Congress’s delegation of the purse much more constitutionally problematic, not less: when the CFPB enjoys so much enforcement power and policymaking discretion, the other aspects of our government’s constitutional structure need all the more protection. As Scalia urged in Mistretta: “Precisely because the scope of delegation is largely uncontrollable by the courts, we must be particularly rigorous in preserving the Constitution’s structural restrictions that deter excessive delegation.”

A few years ago, when the D.C. Circuit declared the CFPB’s independence from the president unconstitutional, then-Judge Kavanaugh briefly mentioned the CFPB’s fiscal independence in a footnote, but suggested that the “CFPB’s exemption from the ordinary appropriations process is at most just ‘extra icing’ on unconstitutional ‘cake already frosted.’” As much as I agree with his conclusions regarding executive power in that case (as did the Supreme in Seila Law), I think the appropriations problem is far more significant.

Indeed, the constitutional importance of Congress’s power of the purse has only grown all the more salient in recent years. Today appropriations are Congress’s main legislative output, in an era when spending bills are exempt from the sorts of procedural and structural constraints on other legislation. As Prof. Gillian Metzger observes in the opening lines of her recent article, “Appropriations lie at the core of the administrative state.” (If anything, that is an understatement.) And as she adds in her closing lines, “courts should seek to set separation of powers rules that encourage interbranch negotiation. Embracing both of these ideas would not only lead to taking appropriations seriously, it would help to construct a separation of powers doctrine that would better suit our polarized era.”

Perhaps the Supreme Court will do exactly that, in the CFPB litigation. The Fifth Circuit intuited the fundamental constitutional problem at hand, and it began to spell out a doctrinal vocabulary for the most important administrative-state issues of our time. The point could be put even more bluntly than the Fifth Circuit did: Congress delegated away its power of the purse.

Adam J. White is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and co-director of George Mason University’s C. Boyden Gray Center for the Study of the Administrative State.