The End of Deference: The States That Have Rejected Deference, by Daniel M. Ortner

Deference doctrines such as Chevron and Auer continue to receive criticism from members of the judiciary including members of the Supreme Court. In Kisor, the Supreme Court recently considered whether to overturn Auer and stop deferring to administrative interpretations of their own regulations. Supporters of deference to administrative agencies issued dire warnings that without deference the administrative state would be unable to properly function. Ultimately, a fractured Supreme Court issued a decision which retained Auer deference, but sharply limited the circumstances where it would apply.

However, while the Supreme Court has chosen incremental reform rather than a more dramatic rejection of deference, several states in recent years have made a different and more dramatic decision. At least seven state supreme courts have issued decisions that decisively reject Chevron or Auer like deference. And two more states have rejected deference via legislation or referendum.

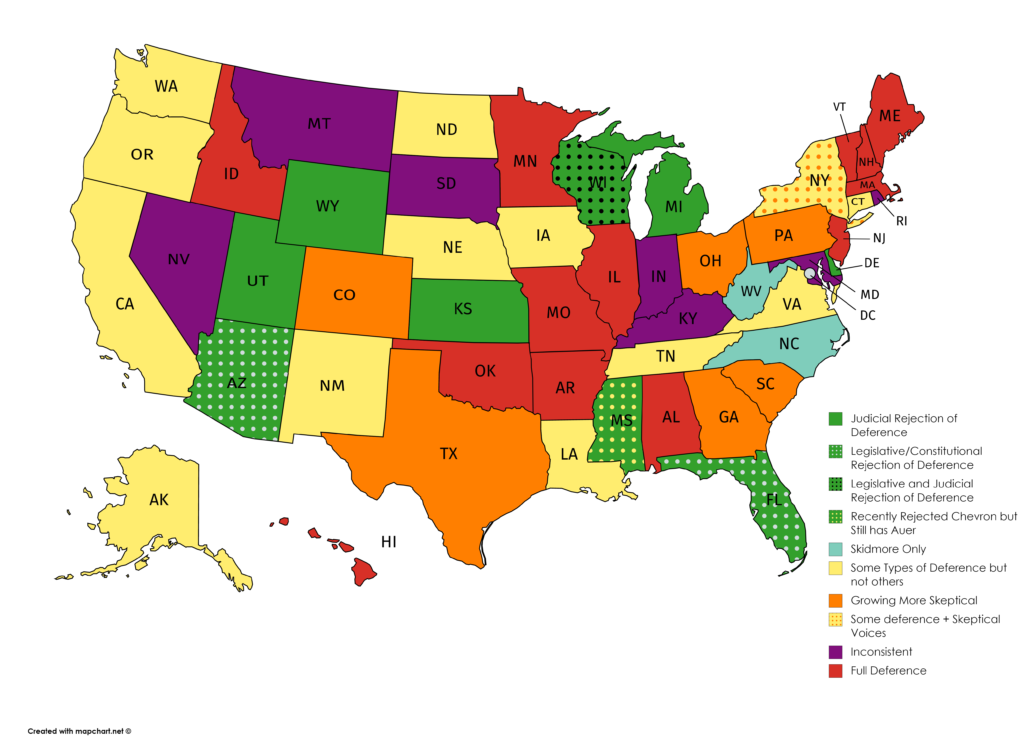

In light of these dramatic changes, I conducted the first fifty state survey of state deference doctrines since 2008. What I found can be described as a (sometimes quiet) revolution. The states that have fully rejected deference have done so with significant fanfare and a vocal rejection of the notion that the judiciary can delegate the power of judicial interpretation to the executive branch. But just as dramatically, even states that have not gone so far as to reject deference have shown increasing skepticism and apply deference in only a narrow and narrowing category of circumstances. And there are deference skeptics sitting on many other courts across the country. The move away from deference has the force of momentum and powerful arguments in its favor. On the other hand, Courts supporting deference are doing so largely out of inertia with largely cursory opinions justifying the need for deference. And even Courts continuing to apply deference are increasingly doing so apologetically and hesitantly.

You can look to my draft article on SSRN, entitled The End of Deference: How States Are Leading a (Sometimes Quiet) Revolution Against Administrative Deference Doctrines, for my full analysis and categorization of all of the states. Here’s the big picture:

But in this short post I want to focus on the states that have most dramatically departed from deference: Arizona, Delaware, Florida, Kansas, Michigan, Mississippi, Utah, Wisconsin, Wyoming,

Only one of these states (Delaware) is a longtime skeptic of deference, and so the shift away is a very recent phenomenon, as state supreme courts have increasingly recognized that deference to agency interpretations of law and regulation violates fundamental separation of powers principals.

The modern trend away from deference began in 2008 when Michigan rejected the call to adopt Chevron-like deference, emphasizing that the Chevron standard is highly confusing and difficult to apply, and that “the unyielding deference to agency statutory construction required by Chevron conflicts with this state’s administrative law jurisprudence and with … separation of powers principles.”

Shortly afterwards, the Wyoming Supreme Court appears to have abandoned deference, though it did not issue a detailed explanation of its decision.\

Kansas followed suit a few years later, declaring that the doctrine of deference “has been abandoned, abrogated, disallowed, disapproved, ousted, overruled, and permanently relegated to the history books where it will never again affect the outcome of an appeal.”

The Utah Supreme Court followed up with a series of three decisions, each increasingly strident in its anti-deference tone. In the last of these, Justice Thomas R. Lee wrote an opinion which rejected Auer like deference and declared that it “makes little sense for [the court] to defer to the agency’s interpretation of law of its own making” because doing so “would place the power to write the law and the power to authoritatively interpret it into the same hands” and “[t]hat would be troubling, if not unconstitutional.” I wrote about this decision on this blog shortly after it was decided.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court next rejected deference in a lengthy and highly detailed 2018 opinion. The Court recognized that it had for decades applied a highly deferential standard of review for agency interpretations modelled after federal law. However, the Court also found alarmingly that it had never “determin[ed] whether this was consistent with the allocation of governmental power amongst the three branches.” The Court then found that deference results in the abdication of core judicial powers. Indeed, “[n]o aspect of the judicial power is more fundamental than the judiciary’s exclusive responsibility to exercise judgment in cases and controversies arising under the law.”

And in 2018 the Mississippi Supreme Court also rejected Chevron like deference. The Court recognized that deference was problematic “under Mississippi’s strict constitutional separation of powers.” Accordingly the Court repudiated Chevron like deference in order to “step fully into the role the Constitution of 1890 provides for the courts and the courts alone, to interpret statutes.” Since the case only dealt with a question of statutory interpretation, the Court cabined its analysis to only agency interpretations of statutes, and so the continued viability of Auer-like deference in Mississippi is yet to be determined.

2018 was also a dramatic year of legislative and constitutional reform. In April 2018, Arizona Governor Doug Ducey became the first Governor in the country to sign into law a statute (HB 2238) which curtails judicial deference for administrative agencies. This bill was advanced by the Goldwater Institute, a libertarian public interest law firm and policy organization. Goldwater argued that the bill would “level the playing field for private entities,” “remove[] the thumb from the scale for agencies” and “curb[] their immense, abusive power.”

Then, in November, the voters of Florida approved a state constitutional amendment that abolished deference to administrative agencies. Of all of the states to reject deference in recent years, Florida may be the most significant of them all. It is the only state where the people of the state have directly voted and ratified an amendment that abolished deference. Florida is also one of the largest states in the country and so what impact this amendment has in Florida will be particularly influential in other states considering abolishing deference. And perhaps most importantly of all, while some of the states to judicially reject deference were somewhat skeptical or tepid about deference for a while, Florida was one of the most deferential states in the country right up until the passing of the amendment. Finally, the amendment has already been cited dozens of times since it went into effect on January 8, 2019, and it appears to have already been outcome determinative in at least one controversial decision involving whether a landowner would be allowed to drill for oil in the everglades.

Rounding out the year, the Wisconsin legislature passed a law the ratified the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s Tetra Tech decision.

While 2019 was not as dramatic a year as 2018, there was still some forward momentum. The Georgia Supreme Court granted certiorari to determine whether deference “is in tension with our role as the principal interpreter of Georgia law.” The Georgia Supreme Court ultimately decided that the regulation in question was not ambiguous and so it did not resolve the question. However, it emphasized that deference would be exceedingly rare because “[a]fter using all tools of construction, there are few statutes or regulations that are truly ambiguous.” And there is a case before the Georgia Supreme Court right now which may again raise the question of whether deference should continue. It also appears likely that Mississippi will consider this year whether Auer-like deference continues to apply, as will Arkansas. And so the (sometimes quiet) revolution against deference continues.

Daniel M. Ortner is an attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation, a public interest law firm that litigates for individual liberty and the separation of powers. He previously clerked for Justice Thomas R. Lee of the Utah Supreme Court and Judge Kent A. Jordan of the Third Circuit Court of Appeals.