Two New Papers to SSRN: Gaming Certiorari and Civil Rights Litigation in the Lower Courts

I’m pleased to report that I’ve just posted two papers to SSRN, both co-authored with my friend and colleague Paul Stancil. The first — Gaming Certiorari — is forthcoming in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review. The second — Civil Rights Litigation in the Lower Courts: The Justice Barrett Edition — is forthcoming in the Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology. Using game theory, Gaming Certiorari models certiorari to explore how lower courts (in theory) could reverse engineer the Supreme Court’s certiorari process to evade review. Civil Rights Litigation in the Lower Courts then applies that model to qualified immunity.*

These were fun articles to write because Paul is a modeler who likes to think through decision-making in a rigorous, step-by-step way. I learned a lot from working with him (indeed, you can see Paul’s influence in the game-theory section of Congress’s Anti-Removal Power, which I discussed here a couple of months back).

I mention these articles at Notice & Comment because we use administrative law to examine the Supreme Court’s certiorari process. As you may recall, in 2019’s Kisor v. Wilkie, Justice Kagan — in part for a four-justice plurality — wrote a decision that retained Auer deference but nonetheless limited it. Because of stare decisis, and against the backdrop of the new limits put on Auer, Chief Justice Roberts concurred in part, thus forming a majority; Roberts declined, however, to join Kagan’s first-principles defense of deference. Four justices would have overruled Auer outright.

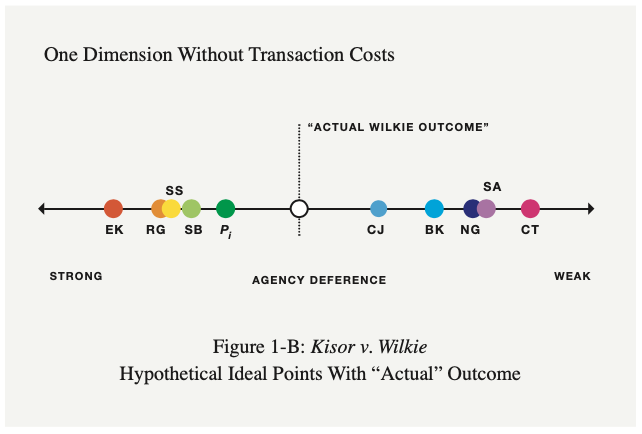

In Gaming Certiorari, Paul and I try to think through the certiorari calculus and opinion-assigning process to understand how a case like Kisor came to be. This is where Paul’s modeling skills shine. First, we model the opinion-assignment process along a single dimension, and from that determine whether certiorari is likely:

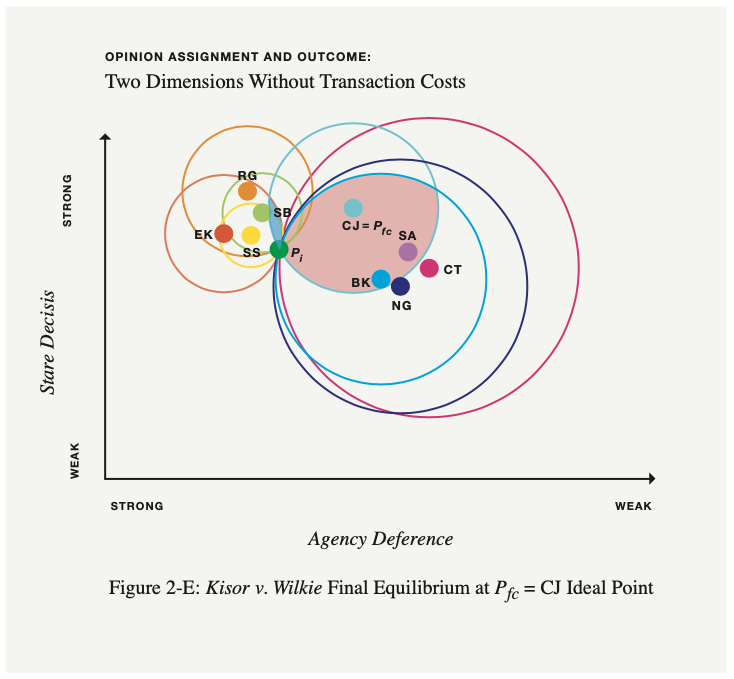

Using only a single dimension (how much deference is appropriate), however, doesn’t show why the opinion didn’t end up at the Chief Justice’s ideal point on that dimension (assuming it didn’t, which I think is a fair assumption). Thus, to improve our model, we explored the issue with a second dimension added (stare decisis):

We think this two-dimensional analysis is more useful.

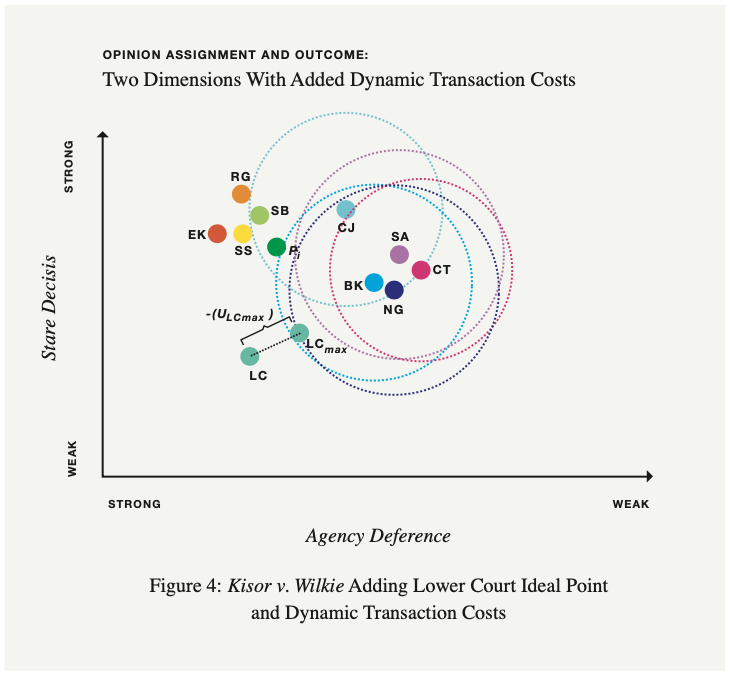

With this model in place, we then introduce the concepts of transaction costs and indifference to explain how lower court judges could — in theory — prevent some cert grants, even though that obviously didn’t happen in Kisor itself.

Suffice it to say, there is a lot more going on in our model and papers than I can describe in a blog post. Hopefully, however, this discussion of what happened in Kisor whets your appetite. Comments are definitely appreciated.

* Here are the abstracts.

First, Gaming Certiorari:

Just how “supreme” is the Supreme Court? By most accounts, the Supreme Court sits atop of the nation’s judicial hierarchy and—at least among judges—has the last word on what the law means. Yet this conventional wisdom overlooks something important: The Supreme Court’s ability to “say what the law is” is limited both by the cases presented to it and the manner of their presentation. This means that the Supreme Court’s supremacy in a sense depends on how lower courts tee cases up for the justices, which in turns means that lower-court judges—acting strategically—can influence which cases the Supreme Court decides. By understanding how the certiorari process works, lower-court judges can reverse engineer their decisions to make certiorari more or less attractive for the justices. It is more difficult, for example, for the justices to review decisions with cursory analysis, fact-bound rationales, or alternative holdings, and these or similar techniques are often available to a lower court seeking to avoid the Supreme Court’s attention.

This Article focuses on lower-court decisions that have been designed to evade or attract Supreme Court review. First, we offer a game theoretical model of the certiorari process to demonstrate how lower courts can manipulate certiorari. Second, using that model, we examine the emergence and operation of the Supreme Court’s so-called “shadow docket,” which—via summary reversal—allows the Supreme Court to reverse a lower court’s decision without expending the costs ordinarily associated with certiorari, and so can be understood as a tool to prevent some form of lower court manipulation. Third, we explore the doctrinal and normative implications of gaming certiorari, with particular focus on the externalities that it creates. Finally, we offer a menu of admittedly imperfect options to address efforts to game certiorari. Ultimately, though, the purpose of this Article is not to solve the problem but instead to present a more nuanced understanding of the judiciary as a whole.

Second, Civil Rights Litigation in the Lower Courts:

Now that Justice Amy Coney Barrett has joined the United States Supreme Court, most observers predict the law will shift on many issues. This common view presumably contains at least some truth. The conventional wisdom, however, overlooks something important: the Supreme Court’s ability to shift the law is constrained by the cases presented to it and how they are presented. Lower courts are thus an important part of the equation.

Elsewhere, the authors have offered a model of certiorari to demonstrate how lower courts in theory can design their decisions to evade Supreme Court review; they also explain why such “cert-proofing” tools are problematic. In this Article, they apply that model to civil rights litigation involving qualified immunity, with particular focus on Justice Barrett’s confirmation. On the assumption that Barrett’s views will be more like those of the late Justice Antonin Scalia (for whom she clerked) than those of the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (whom she replaced), the model predicts lower court judges who do not share Barrett’s views will be tempted, at the margins, to try to evade Supreme Court review. This temptation may be particularly strong for cases that involve qualified immunity, which present unique cert-proofing opportunities. At the same time, the model predicts judges who do share Barrett’s views will be less inclined to use such tools. Thus, although there likely will be no meaningful change in how most cases are decided, the upshot of the model is that in marginal cases it is possible that lower courts will change how they address civil rights litigation.