What Is a FOIA “Record”? Some Thoughts on D.C. Circuit’s Decision in AILA v. EOIR

One of the cases I discussed during my presentation on developments in agency adjudication at the annual ABA Administrative Law Conference last week was the D.C. Circuit’s decision in American Immigration Lawyers Association v. Executive Office for Immigration Review. In this case, the D.C. Circuit addressed a number of important issues related to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, filed by the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA), for disclosure of record reflecting complaints against various immigration judges. The Department of Justice provided the requested records—767 complaints for a total of around 16,000 pages of records—but redacted certain information, including the immigration judges’ names and other “non-responsive” information.

AILA challenged both redaction decisions by the agency, and the D.C. Circuit somewhat agreed. As to the redaction of the judges’ names, the D.C. Circuit held that a blanket redaction under FOIA Exemption 6 (for personnel or privacy reasons) was inappropriate, and instead if the agency “continues to claim that Exemption 6 warrants withholding the names of all immigration judges, it should make a more particularized showing for defined subgroups of judges or for individual judges.”

As to the redaction of non-responsive documents, the court held that FOIA “does not provide for withholding responsive but non-exempt records or for redacting nonexempt information within responsive records,” but remanded for the agency and district court to assess “whether any of the information impermissibly redacted as non-responsive might be permissibly redacted as statutorily exempt.”

The interesting wrinkle, however, is that the D.C. Circuit did not attempt to define what a “record” is for FOIA purposes, but instead seemed to leave that within the discretion of the particular agency. Over at the Cause of Action blog in a post entitled There Is No Tenth Exemption, James Valvo has more on the case and this particular issue:

In deciding American Immigration Lawyers Association, the D.C. Circuit realized that if the statute requires the disclosure of a record as a unit, the amount of disclosure is going to “depend[] on how one conceives of a ‘record.’”[12] The court did not directly reach that question because it used the agency’s determination that the documents containing the non-responsive redactions were the relevant “records.” However, in so ruling, the court afforded a troubling amount of deference to agencies.

The Court summarized that unlike the Privacy Act, the Presidential Records Act, and the Federal Records Act, FOIA provides no statutory definition for the term “records.” The court then looked to the agencies to provide the definition, writing: “Under FOIA, agencies instead in effect define a ‘record’ when they undertake the process of identifying records that are responsive to a request.”[13] It also afforded some authoritative deference to the Department of Justice Office of Information Policy guidance, which “sets forth a number of considerations for agencies to take into account when determining whether it is appropriate to divide [a responsive] document into discrete ‘records.’”[14] The court found “the dispositive point is that, once an agency itself identifies a particular document or collection of material—such as a chain of emails—as a responsive ‘record,’ the only information the agency may redact from that record is that falling within one of the statutory exemptions.”[15]

There is no legal basis for a court to afford deference to an agency interpretation of a term in a statute that is not organic to that agency. Arguably, it is inappropriate for a court to ever provide deference to agency interpretations.[16] However, the D.C. Circuit has held that because FOIA is not administered by one agency but instead applies across the Executive Branch, “[o]ne agency’s interpretation of FOIA is . . . no more deserving of judicial respect than the interpretation of any other agency.”[17] Further, because statute provides that judicial review in FOIA is under a de novostandard of review, courts should not be permitting agencies to decide what counts as a “record” when requiring them to release a record as a single unit.[18]

As courts, agencies, and requesters begin to internalize the implications of American Immigration Lawyers Association, the definition of a “record” is increasingly going to determine how much information is released to the public. Courts should refrain from deferring to agency attempts, should they arise, to segment records into increasingly smaller sizes.

James Valvo has provided a fascinating update on how the Justice Department may be responding to the D.C. Circuit’s decision:

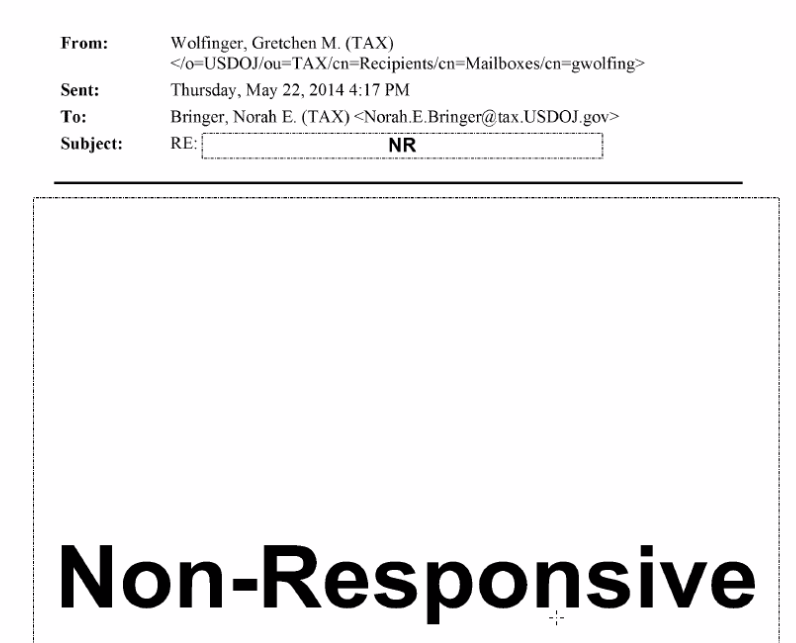

Our prediction that the D.C. Circuit decision in American Immigration Lawyers Association would set up a new fight with federal agencies over the definition of a “record” has come to pass. CoA Institute sent a FOIA request to the Department of Justice – Tax Division (“DOJ-Tax”) seeking access to a record the agency had previously produced with a series of redactions marked as non-responsive. Here is the first page of that record as originally produced.

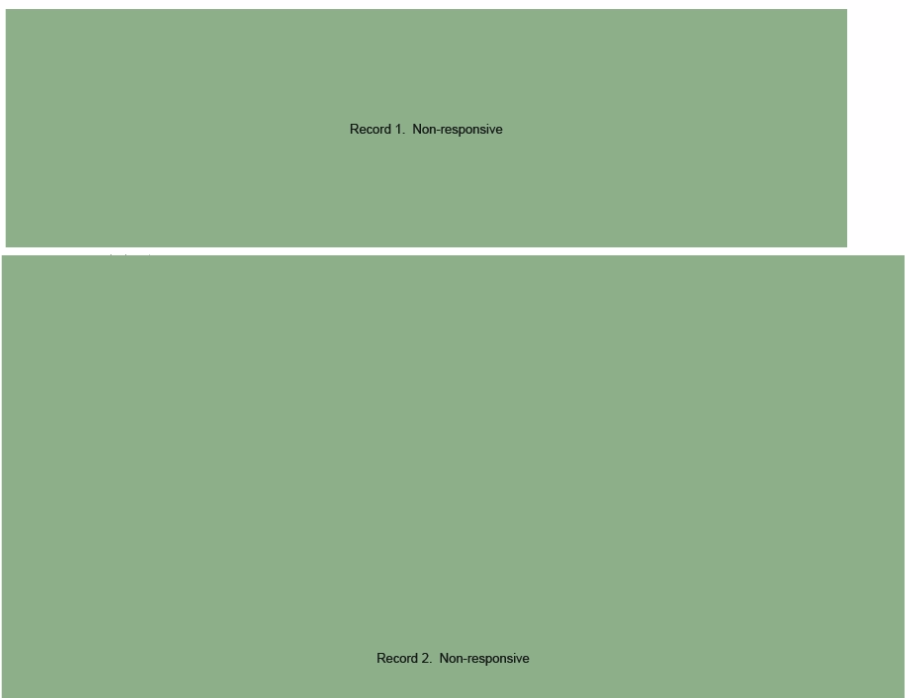

Instead of removing the improper redactions of information and providing the record in full, as per the holding in American Immigration Lawyers Association, DOJ-Tax broke the larger record into a series of smaller records, even so far as to claim that an email header was a different record than the body of that same email. The agency then withheld all but one of those “records” as non-responsive.

Compare the full original here and the full re-produced record here.